A Bark Without a Bite

An intercalary posting

Oseille (Quartidi), 24 Frimaire, CCXXXIV

This is not a completely new article, or even really an article in a proper sense. One of those will arrive in a few days’ time. Here I am simply making a portion of one of my previous ‘Thoughts In and Out of Season’ columns available outside the paywall, because it happens to be obliquely relevant to a few things I have come across in the greater Substack universe. How I came across them, I have to admit, eludes even my understanding; it all has something to do with the algorithm, which knows us better than we know ourselves. This, however, is how it happened as best I can relate: In an attempt better to understand what people mean when they tell me they have tried to reach me by way of ‘restacks’ of some of my articles, I began exploring the Substack app on my phone, and soon found myself drawn into the dark realm of Fairie lying on the other side of its door. I even began re-stacking things myself, including a great deal of material on otters, as well as some depressing stories on political matters, and marveling at the rapidity of the responses this prompted. Then, all at roughly the same time, I had three unrelated and yet oddly uniform experiences that brought me into contact for the first time with the world of Substack philosophy, which seems to be a burgeoning genre, especially among persons of (let’s say) incomplete philosophical training, as well as some with perhaps too much training and too small a capacity for irony or doubt.

The first experience was a fairly mild encounter with individuals of some learning but of overly serious temperament. I had impetuously shared a snippet of footage showing a corgi working out the logistics of getting a long bamboo pole through a narrow doorway, and had prefaced it with some facetious remark along the lines of “Can we at last free ourselves from the damnable lie that we alone qualify as rational animals?” Most of those who responded to it took it as the flippancy it was, but two persons felt a need to raise a grave objection or two. One solemnly pointed out that we alone qualify as ‘semiotic’ animals; the other, even more solemnly, argued at length that reason requires conceptual thinking, which exists, among terrestrial organisms, only in human beings. I should, of course, have simply counseled both of them to lighten up, especially the former, who seemed the more dour and dogmatical of the two. Instead, I could not resist trying to provoke them, without any actual commitment to what I was saying, by stoutly refusing to grant any point they tried to make, and then making contrary arguments. Mind you, I do not in fact have much sympathy for either of their positions; I believe that both semiotic and conceptual consciousness do exist among animals other than ourselves; but the evidence suggestive of this tends to be found chiefly among cetaceans, elephants, corvids, psittacines, and primates, and not so much in corgis (bless their adorable souls). But I was too fascinated by the energy being poured into the debate by my two disputants to desist. The latter of the two, in fact, seemed able and eager to compose whole treatises with his thumbs in the time it would take a man of my generation to find the capitalization key (I suppose he might have been a figment of AI, but I doubt it).

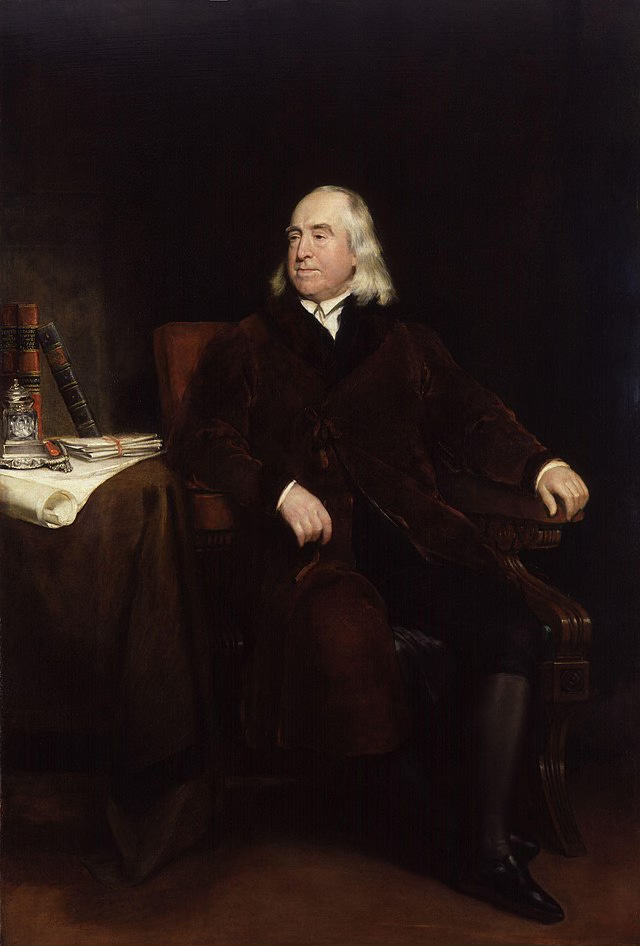

The second experience, which was slightly more irksome, involved someone sending me links to some Substack articles by a fellow going by the moniker ‘Bentham’s Bulldog’, proclaiming in a tone of bluffing bombast that, while ‘analytic’ philosophers make arguments and write clearly and are held to standards of logical solvency, ‘continental’ philosophers merely make assertions and write obscurely and refuse to submit to logical rules. This is an old and tedious line that no one should have much patience for. It certainly fails as a description of analytical process except in its most idealized and self-aggrandizing delusions about itself. By ‘continental’ philosophy, moreover, it turned out that Mr. Bulldog meant certain tendencies found in French poststructuralists and postmodernists of a few decades back and in their American epigones—though he also had his keen canine eyes trained further into the background on the slouching figure of Heidegger and, still further back, on Hegel (who did indeed make impenetrable prose respectable in German and other schools of European thought, but whom only a philosophical illiterate would accuse of a want of dialectical thoroughness). It really was all a bit vacuous. The better part of continental philosophical tradition, from antiquity to the present, has been preserved in texts written with exquisite lucidity—certainly better written than all but the rarest specimens of the larger analytic corpus—and has always operated at a level of conceptual rigor that analytic practice has generally proved incapable of matching, simply because analytic philosophy is bound to methods that make it inhospitable to subtlety, unable to deal well with actual concepts, and largely useless for addressing any problems too intractable to be solved by the application of simple syntactic protocols (vide infra). Really, in many of the most important respects, where matters of true philosophical moment are concerned, novels are far more rigorous than analytic method could ever hope to be. Middlemarch is a much more precise ‘treatise’ in moral philosophy than anything ever written in the analytic mode. So exactly what kind of clarity are we talking about? The syntactic regime of analytic logic, with its inevitable propositional atomism, makes it not only a tragically inadequate instrument for capturing complex ideas; it in fact makes it a source of altogether impenetrable obscurity when applied to such ideas. But what does it matter? At the end of the day, the articles in question were all just so much boilerplate, and really came across as the bluster of someone making excuses for not attempting to think in more than a single simple register—like a piano student who has mastered ‘Chopsticks’ but refuses to advance another step in the direction of Bach or Chopin, arguing that all those notes are just so much aural obscurantism.

It was the third experience, however, that introduced me properly to the mires into which our Substackean peregrinations can lead us if we aren’t careful. Here, let me warn the sensitive among you, I may wax just a little spiteful. Some fellow named Tom Cassidy, clearly quite satisfied with himself about some blow he felt he had leveled at me, dropped me a line telling me that he had ‘commissioned’ (that is, asked for) a review of my book All Things Are Full of Gods by a fellow named Darren Allen, whom Cassidy described as one of the best writers he knew of on the topics of the book. The review was an attack, not so much vigorous as hysterical, and was apparently meant to be devastating; it was certainly belligerent in tone, hyperbolically supercilious, and rhetorically grandiose; it was also, unfortunately, the single most intellectually incompetent attempt at reading any philosophical text—mine or anyone else’s—I have ever seen. Parody would have been wholly impossible. Not only did Allen not understand anything going on in the book; he got everything totally backward. There was not a topic he touched that he did not mangle beyond recognition (even to its nearest close-of-kin). He seemed to think the book argues for a kind of Berkeleyan eidetic metaphysics, while apparently confusing such standard topics as semiotic functions and mental intentionality for wholly different concepts, and also mistaking Kant’s division between representation and the unrepresentable noumenon for some kind of commonsense perceptual realism, and also mistaking the book’s material on the structure of language and symbolic thought for an epistemological theory, and also failing entirely to account for the book’s central arguments regarding the structure of organic life, and also missing the point of all the material on the unity of mind, life, and language, and also… Well, I could go on. Simply enough, it was like reading the opinions—the very strong, arrogant, and truculent opinions—of someone who had read Keats’s ‘To Autumn’, or even Winnie-the-Pooh, only then indignantly to proclaim, “That’s not how you build a toaster at all!” I should have ignored it, I suppose; and, were my conscience not quite as indolent as it often is, I would have done so. I have, after all, seen other eager souls leap into waters whose depths and riptides they had not anticipated (though in most cases with some notion of how, at least, to doggy-paddle). But the thing was so demented in its vicious pomposity and hostility, and so incomparably (even delectably) maladroit, that I found it shamefully easy to slip free of compunction’s claws; I succumbed to my wickedest impulses and re-stacked the review myself, attaching a comment exulting in my discovery of the worst misreading to which any work of mine had ever been subjected. I also communicated to the Cassidy fellow, as he continued to press me and to defend the review he had ‘commissioned’, my frank verdict on Allen’s performance. Allen felt abused, accused me of refusing to acknowledge the substantial points he had made, cursed me as an ivory-tower academic, and so forth.

So it goes. It was unkind of me to take his boorishness as license for mirthful spite, just as it is probably somewhat unkind to rehearse it all now again, and maybe slightly unkind to bring up the other two experiences mentioned above as well. But I have a small point to make. To tell the truth, I have to wonder where all of this is going. I have long thought that theology is the discipline most afflicted by the tendency of eager amateurs to leap into debates for which they are not properly prepared. The reason for this is not hard to find: while most of us do not deceive ourselves that we possess great learning in fields we have not properly studied, most of us think we know a very great deal about the faiths in which we were raised or which we have have willingly adopted (or, for that matter, about the faiths we consciously reject), even if in fact we do not. But I may have been wrong. The truth is that we all feel a certain confidence in our opinions (or else, obviously, they would not be our opinions); and the more our opinions concern what we consider ‘ideas’, the more we are tempted to think we understand all the things we have ideas about. The first two of the experiences mentioned above merely reminded me that people with an appetite for philosophy can often be too enamored of the positions they adopt and can become humorless when they think they see them challenged. I knew that already. The third experience, though, was a genuine epiphany. Philosophy may be—as, say, mathematics cannot be—a particularly fertile field for the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Online philosophy—Substack philosophizing—may not be able to compete with its theological counterpart in the sheer number of earnest amateurs it attracts, but in some ways it may be more pernicious in the hold it exercises over certain minds. It is one thing to commit yourself irrationally to an article of faith, even when you think you are doing so for plausible reasons; but I am not sure that that is a more perilous mental captivity than is a passionate commitment to what you take to be truths of reason. I am a great believer in amateur philosophizing, at least in the mode of honest curiosity, but I feel that all of this has given me yet one more reason to believe that the internet is the death of civilization. We often speak of the virtual realm dividing us into our discrete camps or enclosed ‘silos’, most typically in our political or social pictures of reality. But these insidious micro-cultures—or echo-chambers, I suppose—that encourage us to mistake the chatter circulating and recirculating within their quarantined arenas for the clamor of a great cloud of witnesses, confirming our beliefs for us over and over again, exist wherever two or three are gathered together in the name of a pet obsession. The problem is not the democratization of knowledge, but its inevitable barbarization—the loss of any concept of the difference between truth and fantasy, but also (and no less catastrophically) of the difference between the desire for knowledge and its possession.

Anyway, before I grow yet more platitudinous, I shall stop there. Below are those excerpts from an earlier Leaves article that, until now, have languished behind the paywall. I send it out mostly as an idle riposte to that ‘Bulldog’ whom apparently Bentham keeps on a cruelly short chain in a depressingly confined backyard. It is an example of me—in, I hope, a more whimsical than solemn vein—doing precisely what I have said just above one probably should not do: drawing a polemical distinction between analytic and continental traditions (though, in my case, to the former’s disadvantage).

*******

§3: Wovon man nicht sprechen kann…

Almost twenty-five years ago, while seated at a table in a seminar room with several colleagues in Princeton, I made an assertion about the ontology of the ‘participation’ (methexis, metousia, metochē) of creatures in God. To this, a certain Scottish theologian with a devotion to Barth responded by asking me pointedly whether I could state my ‘proposition’ in logical notation, the obvious implication being that this was an acid test for determining the meaningfulness of my words. I am sure that some of you know that a certain standard of intelligibility is an extremely precious item of commerce in much Anglo-American philosophy, though only because it is a rigidly controlled market, like that of diamonds, in which value is preserved by a false narrative of scarcity. At least, you may know how often analytic philosophers, many of whom speak in carefully cultivated Oxbridge accents even if they come from Omaha, are perfectly willing to bluff their ways past interesting discussions and languidly to polish their own reputations as exquisitely severe logicians by claiming in response to perfectly understandable assertions that they have no idea what their interlocutors’ words could possibly mean. This is often a gesture of petulance rather than principle, but it is a good way of concealing an inability to say something interesting or profound or even ‘meaningful’ oneself. It also constitutes roughly nine-tenths of the analytic tradition’s pretensions to the status of a logical science. (I may be divulging a little too much of my feelings about analytic philosophy here, which in good conciliatory fashion I should say is a very serious and often enlightening intellectual discipline, as well as a few other disingenuous things of that sort, all for the sake of collegial comity.) Not that my Scottish theologian friend was being especially irrational in his demands, but I have to admit that his question was one that could not have been better chosen to get my hackles up (though I tried to behave myself at the time).

You see, yes, as it happens, just about any claim can be stated in logical notation; and this is a very good indication of its redundancy in most cases. Formal logic is an art with roots going back to antiquity and achieving some of its most refined categorizations in the late Middle Ages; but, at least since the time of Frege, it has been something of a neurotic habit among analytic thinkers to act as if a pseudo-algebraic translation of even the simplest and most pellucid of propositions (or, as the perverse among us might wickedly say, sentences) must be susceptible of translation into what is, at the end of the day, only a form of shorthand that is in most cases worthless outside a specific context of actual conceptual topics. More often than not, to a staggeringly preponderant degree, the use of such notation is a pointless act of algorithmic compression that does not even function like a proper algorithm, because it immediately needs to be expanded again into the conceptual forms that it can only shadow forth in order to say anything at all. When we are talking about actual ideas (with which analytic philosophy has a hard time dealing) with very specific and subtle nuances (with which analytic philosophy is often incapable of dealing) and even ambiguities (of whose existence most analytic philosophy is unaware on principle), this touchingly pathetic expression of mathematics-envy is usually simply an interruption of meaning that then has to be repaired. One of the recurrent and bizarre experiences any regular reader of philosophical guild journals is likely to suffer is a strange three-step dance, forward and then backward: first something entirely and unambiguously clear is stated in natural language; then its ‘meaningfulness’ is certified by transposition into an intrinsically meaningless abstract quasi-algebraic ‘equation’; and then, to remedy the perplexity achieved by this evacuation of every trace of semantic signification from that phase of the argument, the notation is then explained in natural language again, in a way that adds absolutely nothing to what was originally said. I submit, credulous and mystical thrall that I am to continental tradition, that at least two of these steps could safely be omitted. If nothing else, I cannot help but notice how often this notational distillate cannot be conduced again into the form of the original proposition without the supplement of all the semantic content that had to be subtracted to arrive at that tantalizingly and yet annoyingly vapid string of magical sigils. The odd inversion that analytic method has introduced into English-language philosophy is strangely similar to the progressive inversion of the early modern mechanical philosophy from a method for, into the aim of, the sciences. Just as early modern science’s new organon was transformed in many minds from a new opening upon the natural order into a dogmatic prejudice regarding what nature must be, so the minor achievements of analytic method in helping to order one’s expositions of ideas have become in many minds the very essence of truthfulness as such. So yes, again, I dutifully studied logical notation and, at least twenty-five years ago, might have found it easy to ‘reinscribe’ my words in its special grammar. The structure of any sentence can be mapped in a pseudo-mathematical shorthand. But that is a trivial accomplishment.

In all the most significant senses, the actual semantic contents of any meaningful assertion, especially one about the difference between Being and beings (as was the case all those years ago in Princeton), are absent of necessity from any formal logic, and certainly from any logical notation. If the word ‘rose’ signifies the absence of every rose, as Mallarmé tells us, analytic philosophy goes beyond meaning: the logically notated proposition is the absence of every propositional meaning. This is unobjectionable, but there is a twofold problem wherever the difference between method and meaning is forgotten, one that renders all too much analytic philosophizing trivial and ultimately irrational. First there is the unexamined notion that all propositions can and should be wholly reduced to an entirely structuralist set of relations in order to be intelligible, such that the real contents of words and ideas are only indifferent tokens of a mere category of abstract logical functions; only thus can they be certified as meaningful or true. This is like saying that every phenomenon is nothing but an expression of the bare mathematical laws of physics, which is to say what belongs properly to the realm of absolute mathematical quantities like mass and velocity, while everything else—qualitative experience, psychology, difficult ideas, impressions, creative intuitions, language itself—adds up only to secondary and accidental effects that are in an ultimate sense unreal. Then too, to come to the second fold of our twofold difficulty, this brings out the weakness in analytic tradition that makes it an all but useless instrument for thinking about anything, and in fact one whose chief function is to make thinking almost impossible, but to do so with the appearance of having achieved some sort of greater clarity. In the end, it makes tautology the final goal of philosophy, and that a tautology utterly drained of every reference. The profoundest philosophical truth is A=A. A particularly sterile logical atomism becomes a rational nihilism.

So, whatever the words a philosopher may employ, the constant impulse within this method is to thrash them into submission; and it is inevitable that the analytic philosopher must treat all words as being timelessly univocal in meaning. Any ambiguities produced by differences in meaning across different epochs, no matter how subtle, render the method more or less useless. I have a vividly unpleasant memory of attending a paper by a grad student trying to demonstrate that Aristotelian aetiology is incoherent because it equivocates in its assertions about causes; the entire argument rested on a catachresis, however, inasmuch as the young philosopher was presuming throughout that what Aristotle called an ‘aitia’ or ‘aition’ was simply meant to be the same propositional simple as what we mean today when we speak of a mechanistic ‘cause’. The historical and conceptual obliviousness was not his fault, however, as he was merely doing philosophy the way he had been taught to do it, expecting not so much that his formal logic should be shaped by the concepts at issue as that all concepts must correspond to the formal logic, to the extent that all particular meaning ought to be treated as accidental to the rules of the game. Well, to my mind it seems obvious that pure analytic philosophy is a misunderstanding of both language and reason. True philosophy should always be dependent upon, or at least qualified by, a keen historical, social, and linguistic consciousness. It is synthetic, not merely analytic. It is hermeneutical, not algorithmic. It is historically contingent, not abstractly absolute. It has to be because otherwise it is about nothing. True philosophy does not dismiss ambiguities and aporias as meaningless or nonsensical, but instead recognizes them as moments of possible awakening from unexamined prejudices, and explores them in as many modalities and with as much subtlety as possible.

§4: Tautology and Dialectic

This is an old issue, as it happens. The problem is not simply that analytic method requires an ideal of ‘correctness’ that, at the end of the day, resolves into tautology. This is true of all formal logic, so long as we take ‘formal’ to refer only to syntactic or ‘geometrical’ coherence, and not the actual forms or conceptual contents that are impressed upon that logic: the semantics of thought, the signifier and the signified, the meaning that can be determined only by a hermeneutical patience with contingencies and with the particular ‘word game’, as Wittgenstein says, that we are playing. A basic modus ponens syllogism can be impeccably valid in formal terms even if the particular contents of its theses and conclusion are utterly absurd. Humpty Dumpty was an elegantly exact logician, formally speaking, but I think it fair to say he was a little shaky on his premises (with, as we know, tragic results). This was the great challenge and singular genius of Hegel’s Wissenschaft der Logik in proposing a logical method based not on the formal rules as such, but on the actual contents of the ideas from which we always begin, and on the dialectical examination of how every concept always presumes and contains its opposite, and on the dynamism by which these oppositions refine our thinking in a synthetic act of reasoning that then generates further dialectical negotiations. What makes analytic tradition frequently so sterile an occupation is not that it practices a rigid formal method (though even that is often more appearance than reality), but rather that it alone among philosophical schools persists in locating truth or meaning in the method itself instead of in the concepts to which it is applied. This is rather like the physicalist tendency to mistake the mathematically quantifiable limit conditions of physics itself for the absolute reality of such things as life or consciousness (and we all know what a barbaric error that is).

I confess that I am a Substack monogamist and only read you. Valuing my time on Earth, I resist the gentle tyranny of platforms that flatter the illusion of endless profundity while quietly shrinking the soul’s attention span to the width of a comment box, promising gnosis and delivering agitation. I am not surprised by your diagnosis of multiplying examples of bad philosophy performed at speed, but if against all odds the algorithm has led you to places worthwhile, recommendations would be greatly appreciated.

Have only read the top part of this article for now. But. Take this with an appropriate amount of salt because I'm still a complete philosophy dilettante who hasn't read much (working on it though) but to me the whole schtick about supposed analytic lucidity compared to continental haziness always seems built on the spurious idea that formal precision somehow equals communicative clarity, and that seems so flagrantly, transparently untrue to me that I don't really understand why anyone takes it seriously. Really? The tradition that loves to articulate itself in interminable logical notation where ordinary language would be much more intelligible? In any case continental thought has been so massively cross-pollinated with the broader humanities and social sciences at this point that it's surely accrued a great deal of communicative clarity from that alone, whereas analytic philosophers mostly just write for other analytic philosophers. I dunno.

Re: the Darren Allen review, aside from the glaring strawmen, what really struck me is how bizarrely mean-spirited the whole thing is at times. When I initially read it (appropriately, while relieving myself in the bathroom), there was a point in the footnotes where he, more or less, argued that he can extrapolate your impotence as a metaphysician simply from how unfunny your book is (if memory serves he took umbrage with jokes about Hephaistos's drinking, or something like that?). I might be misrepresenting that slightly but I'm about 90% sure that was his claim, perhaps you remember it as well. I'm used to seeing people exchange jabs in these corners of Substack, but it was so strangely, acutely spiteful that it genuinely took me aback. Made it all the funnier that he accused your conduct as being nasty. He's since deleted that part from the footnotes. One can only wonder why. lmao