Beckett's Last Theorem

Or: The Little Red Zeugma Who Couldn't

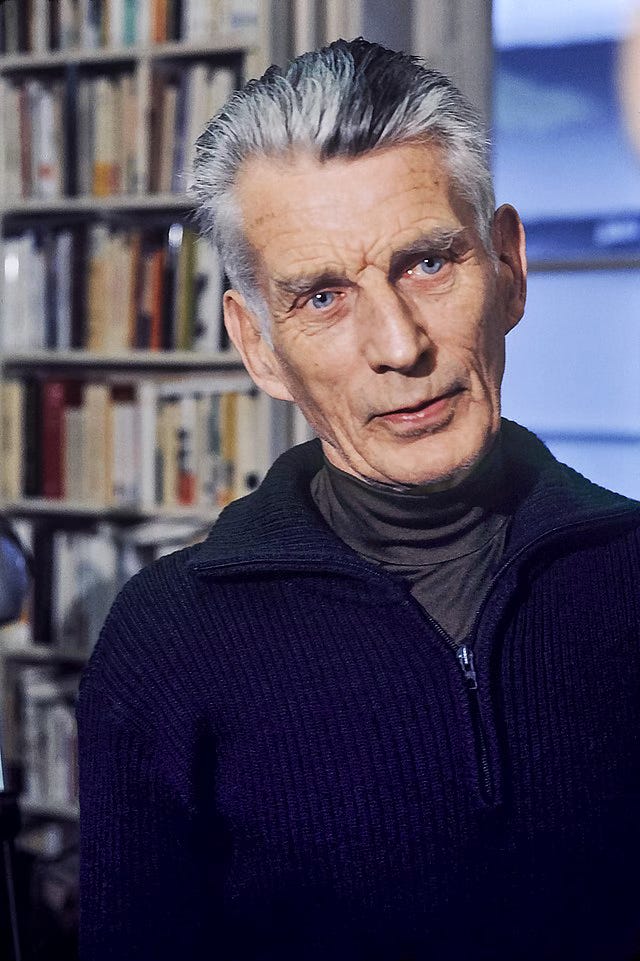

Here is an update on the contest proposed in my previous post regarding the translation into French of a feeble witticism dependent upon a somewhat (vaguely) zeugmatical use of the word ‘know’ in English. As I noted there, the problem is that the equivocal—or, at any rate, analogical—duplicity of the word ‘know’ is not present in any French verb, in that the word for knowing ‘how’ or ‘that’ is savoir, while the word for knowing ‘of’ is connaître. As I also noted, however, Samuel Beckett is reported to have remarked in passing that he believed he could get around the difficulty and make the joke work in French; then, however, and rather inconsiderately it seems to me, he died. I do not mean he died right at that moment; indeed, decades passed between his casual boast and his demise; but, even so, he went to his long home with the secret still held close to his vest, leaving all of us hanging desperately stretched out on tenterhooks. One reader, B. C. Taylor, has suggested that this conundrum be remembered as ‘Beckett’s Last Theorem’. This is an exquisitely pleasing suggestion. It holds out the hope that a century from now, if the human race is still unexpectedly in existence, some brilliant mathematician—or, rather, linguist—will find the solution, to the wonderment of the world.

Anyway, to refresh everyone’s memory, the original jest goes like this: A man at a bar is nipped on the ankle by a small terrier, which the bartender tells him belongs to the piano player. The man goes to the piano player and says, “Do you know your dog just bit my ankle?” And the piano player replies, “No, but if you hum a few bars, I can wing it.”

So, here are some of the proposed solutions thus far.

Gaspard de La Rochère writes: “Hey David, French fan of yours here, I tried translating the zeugma and came up with this: Un homme, assis à un bar, se fait mordre la cheville par un terrier ; le barman lui explique qu’il appartient au pianiste. L’homme va voir le pianiste et lui dit : « Est-ce que tu mesures ce qui vient de se passer ? » Ce à quoi le pianiste répond : « Non, mais si tu en fredonnes quelques-unes, je peux essayer. »”

I appreciate the ingenuity, but alas cannot accept this answer, since the entire point of the joke is that the pianist should mistake the information that his dog has bitten someone for the title of a song, and that misunderstanding is not reproduced in this rendering of the tale; so the different meanings of savoir and connaître remain unreconciled in any quasi-zeugmatical tertium quid.

A reader who goes by the handle FV wrote: “How about: Êtes-vous au courant de votre chien me mordant la cheville?” To which Rob Grayson responded: “Professional French to English translator here. I would say the proposed French is at best unidiomatic and at worst ungrammatical. If one wished to use the expression "au courant", one would rather say something like "Êtes-vous au courant que votre chien vient de me mordre la cheville?" Unfortunately I have no viable translation to propose. I'm intrigued to see whether this is a circle anyone else can square.”

I am in agreement with Rob’s objection.

Then the scholar and publisher Cyril Soler sent me the following email:

Dear Dr. Hart,

Your translation puzzle brings to mind the flexibility of classical French, where 'savoir' could readily encompass both factual knowledge and acquaintance with arts or disciplines—one might 'savoir les mathématiques' just as naturally as one might 'savoir que 2 et 2 font 4.'

Drawing on this tradition, still alive in educated discourse, I propose:

« Votre chien m'a mordu, le savez-vous ? »

Were it delivered with the biting inflection characteristic of the local gentry—where one is never quite certain if faced with a question, a challenge, or a threat—this construction would preserve the zeugmatic ambiguity of the English "know," allowing the pianist's response to function as intended. The placement of "le savez-vous" at the end maintains both possible readings: awareness of an incident and familiarity with what could be construed as a musical title.

While modern French often distinguishes between 'savoir' and 'connaître,' this construction harks back to a more nuanced usage that accommodates both senses within a single verb, much as the English "know" does in your original joke.

Sincerely,

Cyril

Which, when posted by me in the comments section, drew this response from D. Dawsonne: “Non, personne dirait ca dans une situation comme celle-là. Mon avis c'est qu'il est impossible de traduire cette blague en Francais directement. Même si vous utilisez "Tu" au lieu de "vous", la blague n'a pas de sens. C'est trop formelle d'être drôle.”

This seems right enough to me, but in any event we cannot rely on archaisms, elliptical syntax, or rare patrician polish when translating a joke about a bar, a pianist, and a dog. Here we must remain current, terse, and demotic in our diction if the atmosphere of the joke is to survive its metamorphosis from English to French.

A reader named Pierre Whalon then proposed the following: “Dans un bar, un homme se fait mordre la cheville par un petit terrier, dont le barman lui dit qu'il appartient au pianiste. L'homme va voir le pianiste et lui dit : « Ce chien vient de me mordre la cheville. Le connaissez-vous ?». Le pianiste lui répond : « Non, mais si vous en fredonnez quelques mesures, je peux improviser. »”

My first problem with this is that it seems to me that the pianist, if he thinks he is being asked about a song (chanson, chansonnette), ought to hear the question as “la connaissez-vous?” That’s not really an issue, of course, since the indeterminate “le” is perfectly natural there. But somehow this makes it clear to me that the joke rendered thus depends on a simple misunderstanding of reference rather than the spectre of a zeugma. Perhaps it would work somewhat better if the story went: “Un homme dans un bar se fait mordre la cheville par une petite chienne, qui, selon le barman, appartient au pianiste. L'homme va voir le pianiste et lui dit : « Cette chienne vient de me mordre la cheville. La connaissez-vous ?». Le pianiste lui répond : « Non, mais si vous en fredonnez quelques mesures, je peux improviser. »” But that still doesn’t fix things. Here, again, the old familiar problem returns. I am certain that whatever comic force this admittedly poor joke commands depends entirely upon the misconstrual of a verb by virtue of its ever so slightly zeugmatical duplicity. Monsieur Whalon’s proposal is the best so far, but I cannot in perfect purity of conscience accept it as the true solution to Beckett’s Last Theorem.

Our long, twilight struggle with the intractability of the problem continues, it seems, and may well do so until the last trump has sounded, when Beckett himself will be able finally to dispel the clouds of our agonized ignorance. But keep the suggestions coming. Perhaps someone out there will be able to find a way of getting this joke across the English Channel intact and breathing.

DBH

Oh, PS, since we’re dealing here with things French, and as Christmas is fast approaching, may I recommend a thrilling novel set among the grand châteaux of the Loire Valley entitled The Mystery of the Green Star? It is a masterpiece, staggering in its epic dimensions and spiritual depth. And there’s a penguin in it.

Oh, Oh, PPS, another little contest. In the article that appeared here a couple weeks back on Paul Valéry, I at one point described absinthe as la sorcière glauque, just to see whether anyone would flaunt his or her abstruse knowledge by calling out the source of the phrase. As yet, no one has piped up. So, another little contest: Who was it who first dubbed absinthe “the glaucous witch,” and where? The prize at stake is a secret, but it too may involve a penguin.

Max Beerbohm's Enoch Soames comes to mind.

Whatever else may hereafter befall, having been quoted by name in these hallowed pages, I can now die happy.