Books for a Very Long Journey XVI

Accidental aphorists, some memoirs, interrogations of Heaven and of the soul, wartime satires, bad poetry...

§171 Ilarie Voronca, The Confessions of a False Soul: Voronca was the nom de guerre of Eduard Isidor Marcus (1903-1946), a Jewish Romanian author who emigrated to France in 1933; for a time, he was one of the most influential of the surrealists, and in retrospect seems in many ways the most temperamentally attractive among them. He was also at once terrifically brave and terrifically fragile; he fought with the French resistance during the years of occupation, and then took his own life only a year and a half after the liberation of France. He began his literary career by writing in his native tongue, but after settling in Paris wrote exclusively in French. Even before his relocation, he had found his true métier as a master of short forms—poems, essays, short stories, vignettes, strange fables. Even his ‘long’ works were never greater in length than could be consumed in a couple hours. His special genius, to which his spare and translucent prose was ideally suited, was for making the dreamlike and fantastic seem utterly ordinary and somehow plausible, and for investing even minor details with a depth of suggestiveness that is at once provoking and satisfying. This, his second novel (1946), has at once the sheen and the consistency of a rainbow—albeit a somewhat disturbing rainbow. Its protagonist is a weary clerk in some minor bureaucracy who goes to a surgical specialist to have his decayed soul removed and replaced with one younger and better. As it is wartime, there is something of a surplus of souls available, and it is one of these, harvested from a young soldier slain in battle, that the surgeon implants in the clerk. The premise is grimly amusing, and is handled with so light a touch that the moral protest against the cruelty of war and of social structures of power never seems ponderous. Needless to say, problems of an altogether metaphysical character arise once the operation has been performed. These, however, are leavened by various other elements of the narrative—a rather endearing love story, a chapter devoted to the wonders of garlic, a tale of a larcenous housemaid, and so on—which carry the tale to its strangely compelling dénouement. It really is greatly entertaining.

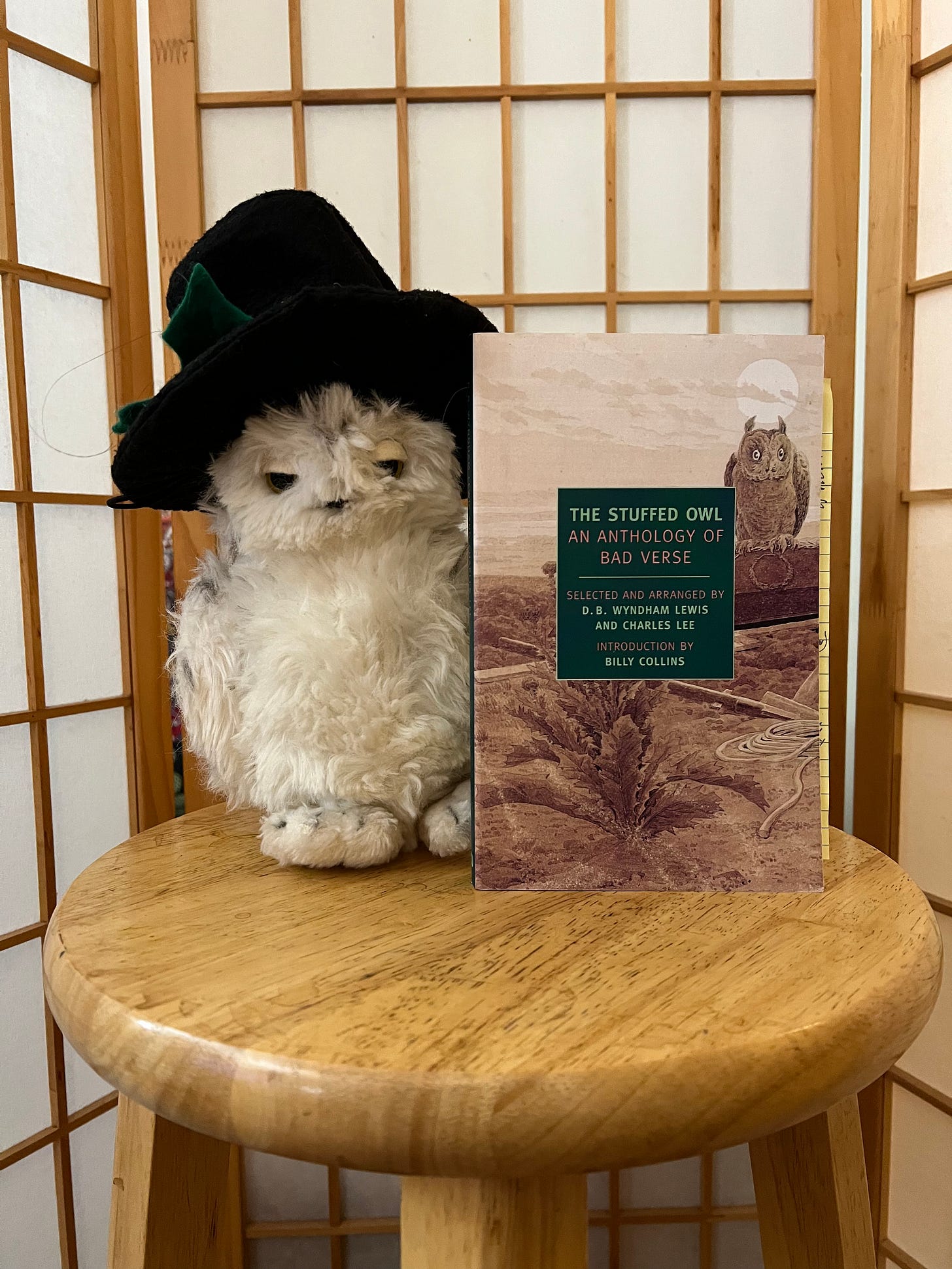

§172 D. B. Wyndham Lewis and Charles Lee eds., The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse: I was recently asked by a friend to name three infallibly hilarious books small enough to be packed in carry-on luggage for an overseas trip. I recommended Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians, Max Beerbohm’s Seven Men, and this justly celebrated collection of ghastly poetry. I was not sure at the time why these three titles occurred to me all at once, but afterward realized that what they shared in common is that each in its way is a satire of Victorian sentimentality and grandiosity. The tone of the satire spans the spectrum from the witheringly harsh to the genially gentle, with Strachey and Beerbohm at either end and The Stuffed Owl (1930) perched placidly midway between them. It would be unjust to describe the anthology as cruel or cutting, but disingenuous to call it affectionate. As the editors make clear in their introduction, there would be no purpose in a collection of extremely bad poetry by incompetent versifiers, which is at once abundantly available and invariably boring; this is a gathering of poems by authors who had all the technical skill one could hope for, and who in many cases exhibited exemplary formal virtuosity, but who nevertheless employed their strengths to produce poetry of astounding lousiness. It is not even a collection of bad poets as such, though there are quite a few of those in its pages; in many cases, the authors are very fine and even great poets indeed; but even Homer nods. Thus we find many figures whom everyone already knows were horrid poets (such as Erasmus Darwin and Martin Farquhar Tupper), many more who would also share that distinction if anyone now remembered them at all (Cornelius Whur…anyone?), others once praised but now generally abominated (like Edward Young), others whose posterity has been unfairly opprobrious but who still have much to answer for (Longfellow, for instance), others not now despised but no longer highly esteemed (Crabbe being an obvious example), still others who left behind a mixed patrimony (either through combining excellent technique with frequent triviality, like Tennyson, or through combining uneven technique with impossible profundity, like Emerson), and then a host of true greats who were nevertheless guilty of occasional glissades into embarrassing doggerel (Dryden, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Byron, Keats…). What almost all of them have in common, the editors note, with Byron being the most obvious exception, is that they were singularly devoid of an active sense of humor, and so as a rule could not recognize when the matter or ambition of their verse became ridiculous, or when it was made all the more ridiculous by their formal mastery of metre and rhyme. To me, for reasons of purely private distaste, the most gratifying inclusions are the ones from Poe, ‘Eulalie’ in particular (though to my way of thinking his entire poetic corpus could have been included with no injustice). It is all somewhat wicked, perhaps, but not without some moral meaning. In its way, The Stuffed Owl was a manifesto of literary modernism and its war against fulsome artificiality, no less than the texts of Pound and Eliot. It does not now occupy quite the monumental eminence of Cathay or The Waste Land, but in all fairness it provides considerably more laughs than either of those.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Leaves in the Wind to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.