Frank (31 August 1935-7 February 2019)

The Desire and Pursuit of the Whole (now out from behind the paywall)

“Sometimes it seems like a bad trade, but bad trades are part of baseball. I mean, who can forget Frank Robinson for Milt Pappas, for God's sake!”

—Bull Durham, opening monologue

If you have no very great interest in baseball (a condition known to science, widely attested in the clinical literature, and apparently on the rise in the younger generation), much of what follows may strike you as both somewhat abstruse and a little tedious. Even if you are an aficionado of the game, you may begin to wonder whether there is a larger point to these reminiscences. But I assure you, I intend to draw a more general reflection from the tale before concluding. First, though, there is moral and emotional obligation to discharge.

This is before all else, you see, a very belated farewell to someone who, inasmuch as he was and is a monumental presence in my life, deserved something far timelier. Had I still been writing regular columns for a certain magazine when he died—three years ago today—I would have rushed to play the gushing encomiast; but, then again, it would have been impossible just then even to feign anything like dignified equanimity, so perhaps it is for the best that circumstances intervened to delay me. One has, as a rule, only a very few childhood heroes, and it is difficult to control one’s sentiments when any of them depart the world. It takes some time to put things in proportion.

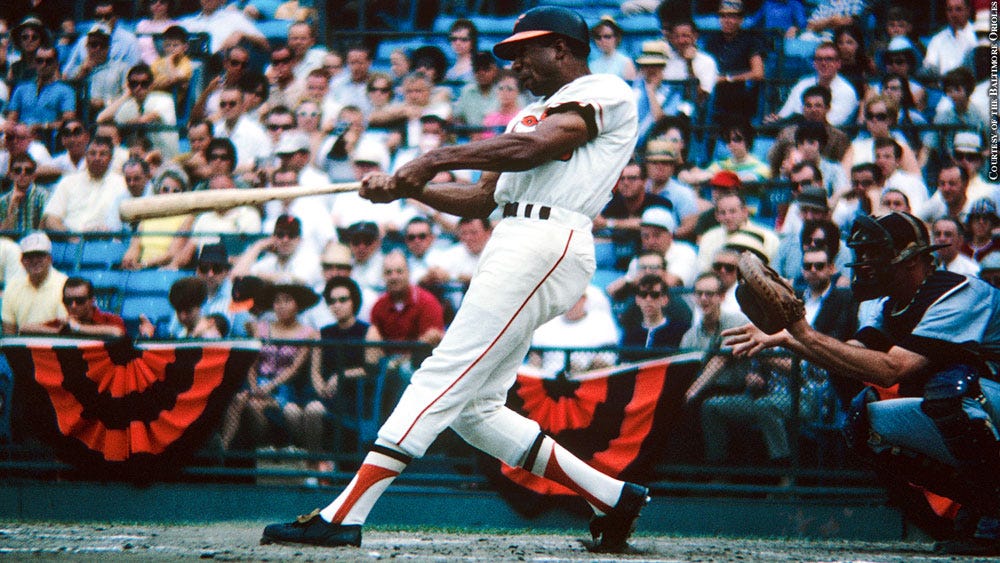

I have loved baseball and the Baltimore Orioles all my life. Admittedly, the latter of those attachments was much easier to sustain during the first two decades of my life, when the Orioles were the team that won more games than any other in the major leagues and were widely regarded as the very model of organizational excellence in the sport. But I have remained faithful during the lean years as well. And a very great part of that loyalty has been nourished by my particular devotion to Frank Robinson, far and away the greatest player ever to wear the Orioles’ uniform, one of the most astonishingly gifted and passionate players in the history of the game, and surely among the most dedicated to the sheer art of playing it well. Mind you, he was on the team for only six seasons (as a player), and only in the first of those was he able to perform at the absolute height of his powers; a serious injury in his second year reduced him to mere magnificence; but since those years happened to coincide with my very, very, very early childhood, they seemed to stretch from everlasting to everlasting. And they were filled with moments of glory, most of which I was unable properly to appreciate until I was older.

I was a very little fellow indeed on June 26, 1970, for instance, and far too young to grasp the significance of what I was seeing as I watched the game being played in RFK Stadium, just down the road from Baltimore in DC, between the Orioles—in those days, widely acknowledged to be “the best damned team in baseball”—and the Senators—who, to put it mildly, were definitely not “the best damned team in baseball.” In both the fifth and sixth innings, Frank came to the plate with the bases loaded (in each case with Dave McNally on third, Don Buford on second, and Paul Blair on first), and both times he hit a grand slam (and, believe me, there were very few cheap home runs in RFK in those days). That in itself, of course, was impressive enough, and it was surely the most spectacular of the many times he brutally shattered the hopes of Washington fans with his bat. But the whole story, told in its entirety, is far more interesting. Far more miraculous, one might almost say. (Really, it belongs properly to the realm of the mythic.)

For one thing, later in the game Robinson was on deck with the bases loaded yet again, but the inning ended before he came to the plate because the hitter ahead of him (and I refuse to recall who it was, for fear it will turn out to have been Brooks) grounded into a double play. I will go to my grave believing, however, that had he reached the plate with all those “ducks on the pond” (aren’t baseball’s traditional metaphors our most splendid national poetry?), he would have hit another home run, probably on the first pitch he saw.

And yet that is not where the wonder of the tale lies, nor does it explain why those particular 8 RBI were especially—even ridiculously—emblematic of the man’s greatness. You see, just the night before, June 25, the Orioles had been in Boston, and had been trailing 7-0 late into the game; but they were the Orioles and they were playing in Fenway, so they had tied the score in the ninth. The game went fifteen, if memory serves, and Boston very nearly won it in the thirteenth; they were prevented from doing so by a brilliant leaping catch in right field by (of course) Frank Robinson, but one that sent him careening into the right field wall and cracking a rib. As a result, when he came to the plate again, he could not lift his arms properly to swing the bat; but he had given no indication of this to anyone. There was a runner at third with two outs, and both infield and outfield were playing him deep, mindful only of his power. He, however, somehow alerted the runner that he was going to lay down an impromptu suicide squeeze, and shocked the defense with a perfect bunt that he beat out by a step, thus plating what turned out to be (again, of course) the run that won the game. All of which makes his two grand slams of the following night...what, precisely? Homeric? Semi-divine?

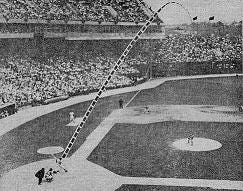

I, at any rate, was in the habit of viewing him as a kind of demigod throughout my childhood—and, to be honest, long thereafter. It was hard not to. His greatest achievements all seemed to be marked by a special kind of grandeur; they were simply on a different scale—of a different magnitude—than even the most impressive feats of most other players. Every time I attended a game in Memorial Stadium, up until the opening of Camden Yards in 1992, the first thing I did after finding my seat was cast a long, lingering, adoring glance at the top of the left field seats to the orange flag flying there, bearing the simple legend “HERE” in black capitals. It marked the place where on May 8, 1966 Robinson had hit a ball entirely out of the stadium. He was the only player ever to do that in a game—and he hit it off of no less a pitcher than Luis Tiant. Understand, the dimensions of those stands were nothing like the left field bleachers in Wrigley Field, and the conditions nothing like Chicago on a windy day. The seating was a great many rows deep and the rise of the stands vertiginously steep. It was a prodigious—in fact, an absolutely titanic—blow, now reckoned at 541 feet, though a mathematician friend of mine assures me that, given the ball’s angle of ascent, this is a very conservative estimate. I choose to believe him. Frank himself, naturally, did not get long to admire the sight of the ball leaving the building; in keeping with the game’s somewhat Confucian etiquette, he no sooner had hit it than he dropped his head and began circling the bases at a quick trot, so as not to seem to be mocking the pitcher.

That was Frank’s annus mirabilis, of course: the year that he led the Orioles to a championship, winning the Triple Crown in a particularly pitching-rich era (.316 BA, 49 HR, 122 RBI, with an OPS of 1.047 and 367 TB), winning his second league MVP, and winning the World Series MVP. The four game sweep of the Dodgers that year, in which the Orioles’ pitching staff and impenetrable defense held LA scoreless for the last 33 innings, ended with a 1-0 Baltimore victory in game four. That lone run came, naturally, off a Frank Robinson home run.

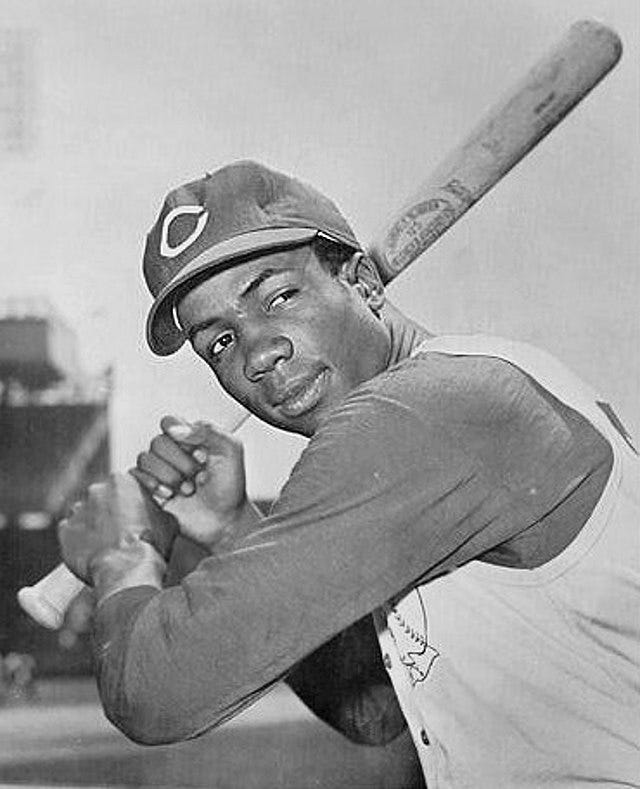

His career has entered into the lore of the game in any number of ways, I should note. He was the only player ever to win the MVP in both leagues (for Cincinnati in 1961 and for Baltimore in 1966). In his first season with the Reds (1956)—which would have come a year earlier but for a shoulder injury that would trouble him on and off throughout his career—his 38 home runs set what was then a record for a rookie. (Since that time, of course, it has been surpassed by vastly inferior talents playing with a far livelier ball in stadiums with far less spacious outfields, aided perhaps on occasion by a soupçon of illicit pharmacology.) He was also, again, one of those rarest of players, a Triple Crown winner. He went to fourteen All-Star games, and was the game MVP in 1971. To this day, he is the all-time leader in slugging percentage (.554) and run-production for the Reds, the oldest franchise in the majors. In Cleveland in 1975, while still a player, he became the first black major league manager. (The most beautiful episode of his tenure there came on April 8 that year, when he won the opening day game by inserting himself as a pinch-hitter and promptly delivering a game-winning home run.) And so on.

His most prominent distinction in baseball legend, however, is rather incidental to his accomplishments on the field. He is more or less universally recognized as the principal player involved in the most unequal trade in the history of the game. In the decade leading up to his glorious 1966 campaign, which was his final more or less entirely healthy year, he had spent a decade compiling seasons of shining excellence in Cincinnati. He had, for instance, followed up his heroic rookie year with a .322 average in his second season. In his first MVP year, 1961, he had led the Reds to the championship with a .323 average, 37 home runs, and 124 RBI, as well as 32 doubles and 7 triples. The following year he raised that to a .342 average, 39 home runs, and 136 RBI, as well as an astonishing 51 doubles and 2 triples. In 1958, he won the Gold Glove (he should have won more, probably, but his hitting overshadowed his defense, as so often happens). I could go on. And yet Cincinnati traded him to Baltimore in December of 1965 in exchange for a very good but not great pitcher, Milt Pappas, as well as a journeyman pitcher named Jack Baldschun and an outfielder named Dick Simpson. (You need not bother looking up their statistics.) Cincinnati’s ownership had come to the bizarrely capricious conclusion that, though Frank was only 30, he was in decline as a player.

Mind you, by Frank’s own standards, 1965 had been a shameful season. By anyone else’s it would have been fairly remarkable (.295 BA, 33 HR, 113 RBI). But that year—and it was the only time this ever happened to him—he had struck out exactly 100 times. For an uncompromising perfectionist like him (and I shall get to that aspect of his personality shortly), this was humiliating. Today, of course, the game is full of players who think nothing of striking out more than 200 times in a season so long as, when they do make contact, they do so with the right launch angle; dazzled and stupefied as they are by the statistical mirages generated by fashionable analyses of mean quantitative effects over the course of a season, they are content to waste countless AB’s by swinging the bat with the same wild abandon no matter what the count. Frank came from a time in which a good batter was expected to shorten his swing when there were two strikes against him, to keep the bat level and attempt to hit the ball on a line or between the middle infielders, and to try to send any outside pitch the other way. This had never really put him at a great disadvantage, since he had a swing that was in fact unnaturally level and he was able to keep it on the plane of the ball much longer than normal, so when he caught a low outside pitch on the end of his bat he could drive it on a line, sometimes over the right field fence. So, for him, to reach three-digits in strikeouts was an intolerable stain on his record.

Not that this explains what the Cincinnati front office was thinking when they agreed to that preposterous transaction. In the event, it was a disastrous decision on their part and a Godsend for the Orioles. Baltimore was already a rising force in the American League, but the addition of Frank Robinson turned them into a team that, even after his departure, exhibited the sort of habitual excellence that set him apart from lesser players. It was the beginning of a golden age for the franchise. And his tenure in Baltimore coincided with its greatest period. For his final three years on the club, the Orioles were one of those “dynasties” that regularly appear on the lists of “greatest teams ever” that cognoscenti of the sport so much enjoy arguing over. Its deep batting order was imposing enough; but what set the team apart was its absurdly talented rotation (four—four—20-game winners in 1971, for instance) and by far the most scintillating array of defensive talent ever assembled on a single field (Brooks Robinson, Paul Blair, and Mark Belanger were merely the most amazing on a team composed almost entirely of amazing fielders). And, during those years, Frank was the team’s acknowledged leader. Naturally, when the players instituted a kangaroo court in 1966, convening after every win to assign penalties for lapses in the field, he served as the judge, appearing at the bar in a wig fabricated from a mop and wielding a bat as a gavel.

Oh, but I am still failing to explain my fascination with the man. The statistical records and the tales of his extraordinary feats on the diamond amply testify to his talents, but cannot capture his peculiar brilliance as a virtuoso of the game—a game, after all, that is almost impossible to play well in its every dimension. Much of that was a matter of personality. He is rightly remembered as one of the most ferocious players the game has ever seen. He hated to lose with an almost insane intensity; and this had two conspicuous effects on his manner of play.

The first was that he approached the game with a kind of controlled recklessness that made him something like a force of nature, not only at the plate but on the basepaths and in the outfield. The only other player of his generation who matched him in temperament was probably Bob Gibson. And, like Gibson, Frank was not at all a nice fellow while the game was on. He rigidly observed the unspoken rule—quaint by today’s standards—that one never fraternized with players from the opposing team. After all, in the course of the game one might have to break up a double-play by sliding into second or third with cleats up, and one must not allow personal sentiment to soften the blow. Not that he was ever trying to hurt anyone as such, but neither was he making any special effort not to hurt anyone. That was simply the code of the game. In 1957 Johnny Logan went on the disabled list for six weeks as a result of Frank’s spikes, and in 1960 a collision with Eddie Matthews at third led to a fistfight that left both men dazed. Only an altogether fearless batter, moreover, would have crowded the plate quite as intimately as Frank did. In his ten years with Cincinnati, he was hit by a pitch 118 times. Admittedly, he was able to do this because apparently his wrists were made of tempered steel. He could turn on an inside pitch with terrific speed and power without pulling it foul. Still, that does not make a fast ball to the ribs any less agonizing.

It was this same recklessness, however, that ultimately cost him the opportunity to finish his career in an appropriate blaze of glory. Of his many injuries over the years, the most consequential came on June 27, 1967, the year after his glorious Triple Crown, MVP, and championship season. He was in his absolute prime. Halfway through the season, he was on a better pace than he had set the year before. With all due respect to Carl Yastrzemski, had Frank remained uninjured he would very likely have taken the Triple Crown again. At that point in his career, he had become simply the best player in the game; and he seemed still to be getting better. But on that day, sliding into second with his customary indifference to life and limb, he struck Al Weis’s knee with his head and suffered a concussion that left him with double vision for a prolonged stretch of the season. He still finished the year (ridiculously enough) with a .311 average, but he was never quite the same hitter again. In later years, he would occasionally wonder aloud how much of himself he had left out there at second base. And then, there were more injuries to come the following year, and at intervals thereafter. Mind you, it is hard to pity him when he is matched against other players; in 1969 he hit .308 and in 1970 .306, and his power numbers still placed him among the elite of the game. But matched against himself, and against the mastery of the game he had achieved in his eleventh season and the first half of his twelfth, he was a much reduced demigod.

The other effect his hatred of losing had on his style of play was a peculiar fastidiousness about doing everything on the field with exacting precision. It was this, I think, that made him for me not merely my favorite baseball player, but also an endlessly fascinating study in the art of pursuing perfection, whatever one’s vocation. In some ways, his unflagging attention to every detail of the game—which made him such an ideal fit for an organization famed in those days for its punctiliousness about mastering the small and least glamorous excellences of the sport—did not always serve him well when he became a manager. He was not at first renowned for his tender solicitude for the feelings of players of inferior talent or less inspired play; he was very much of a generation that believed in challenging rather than encouraging, and he could not always grasp how impossible it was for most of the players he managed to perform at his level; he had to mellow into the rôle, over the course of several seasons with a variety of franchises. But, as a player, he was always and indefatigably driven by his singular will to play the game without flaw. It made him, for example, among the best hitters in the clutch I ever saw. It also made him a true connoisseur of the sport. “Baseball is the most beautiful game in the world,” he is quoted as saying on several occasions, “if you only play it the right way.” Therein, of course, lies the simple secret of all beauty in human action and art.

To this day, I have to say, I often feel that there was something unfinished about Frank’s career (as there is for everyone’s life, I suppose). True, his final numbers as a player were marvelous—.294 BA, 586 HR, 1812 RBI, 2943 BH, 1186 XBH, 5373 TB—but he is definitely one of those greats regarding whom one can only wonder what a career unmarred by injuries would have looked like. Some of those algorithmically generated “alternate world projections” produced by SABR-style mathematicians (based on his RBI and TB per AB when healthy, presuming a career beginning one year earlier and holding to a statistically rational curve over its closing seasons) are staggering; but, given their finally fantastic nature, they are anything but comforting.

There is something galling, moreover, about the “almost but not quite” nature of some of Frank’s final totals: his last years of sporadic playing time and mounting injuries lowered his lifetime average to just below .300; his refusal as a player-manager to put himself in as many games as he should have done (so as not to “show up” the younger players) left him with a home run total tantalizingly short of 600; lost time cost him that magical 3000 mark in hits. It is all rather like that third grand slam he never got to hit or that violently curtailed pursuit of a second consecutive Triple Crown: one knows that, for all the brilliance of his play, he would have shone more brilliantly still had fate favored him more. Of the five greatest field players of his time—Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Roberto Clemente, and his own good self—only Mantle suffered more injuries (and, of course, sabotaged himself with his drinking). It is also somewhat annoying that, of those five, Frank seems at times to be the least clearly remembered by the generations of fans who came along after his playing days had ended. True lovers of the game, needless to say, recognize his importance. No less a player than Mike Schmidt has always cited Frank as his ideal of what a baseball player can and should be, and during his own career he wore Frank’s number 20 in tribute. But casual followers of the sport are likely to be far more cognizant of Mantle, who ultimately accomplished less.

Perhaps, however, I am only imagining that. And it does not really matter, I suppose.

For me, Frank Robinson represents a certain fierce elegance and unremitting excellence in a game I love. But, more than that, he represents the essential nobility of seeking to do anything as well as it can be done. For some reason, he—as much as anyone else in the gallery of my special heroes—has often come to my mind whenever I have found my own will or attention to detail weakening in the course of some task. Somehow the thought of him inspires me to a greater effort even if what I am trying to do is to get a particular sentence just right, or to frame an argument correctly, or to describe something as exactly as possible, or to time a joke in print well, or to find the precise mot juste. It is all but impossible, of course, to realize complete excellence in any endeavor; with the exception of Bach alone, we know of no mere human who ever succeeded at doing anything to absolute and unsurpassable perfection; but we cannot be Bach. This is the land of unlikeness; for the rest of us, the ideal is reflected here below only dimly and fitfully, in the shattered mirror of material existence; so it is always an aid to the soul to be able to look to the examples of those who have struggled against impossibility with rare fidelity as long as they were able.

After all, so long as we do dwell in the land of unlikeness, it is only through our dedication to our own limited crafts and callings that we can begin our ascent toward the Sun of the Good and nourish our souls’ innate “desire and pursuit of the whole.” Any man or woman who does anything intrinsically worth doing—music or poetry, baking or gardening, farming or building, laboring at a hard job or playing a beautiful game—and who strives simply out of the purity of his or her desire for ideal form to do it with consummate skill has done enough to be credited with a life well lived, and has achieved genuine greatness. So it was with Frank Robinson, and this is why I loved the man and was moved to tears when he died, even though when he did so he was full of years. As I say, one has only a few childhood heroes, and it has surely been my great good fortune that he was among mine.

1969? As I recall, both the World Series and the Super Bowl weren’t played that year, for some reason…

Genuinely enjoyed this post (I don't know much about the game, but I felt moved to watch a few highlight clips of Mr. Robinson) - my condolences & RIP to a legend