Gerald McDermott's "Review"

Surveying the Ruins of "First Things"

I have been asked by a number of readers whether I intend to comment upon Gerald McDermott’s truculent and ridiculously misrepresentative “review” of Tradition and Apocalypse—wherein our intrepid warrior in the cause of orthodoxy claims that the book portrays Christian tradition as “bankrupt” (which came as a bit of a surprise to its author, I can tell you). The review appeared on the online site of (as if it needed saying) First Things, where editorial standards have been in tragic decline ever since my dog decided to sever ties with the publication.

One voice (mine) tells me that I should respond: it would be hard to imagine a review that gets the argument of a book more extravagantly backward than McDermott’s does. (Then again, First Things has a positive genius for digging up ever less competent reviewers, so who knows what buried gold the journal has yet to unearth?) About two dozen other reviews of the book have appeared to this point and all of them, even those that have been less than totally sympathetic, have at least gotten the basic line of argument in it right. McDermott’s account, by contrast, is so ludicrously inaccurate that I now feel I must say something, just to reassure those who have not read the book that I have not gone raving mad.

Another voice, however (and one of sounder counsel), advises that I refrain. The eminent and wise Robert Wilken always tells me not to bother to respond to especially silly reviews—and I would take his advice always if I were as eminent or wise as he. After all, life is short and I am busy (and lazy at the same time).

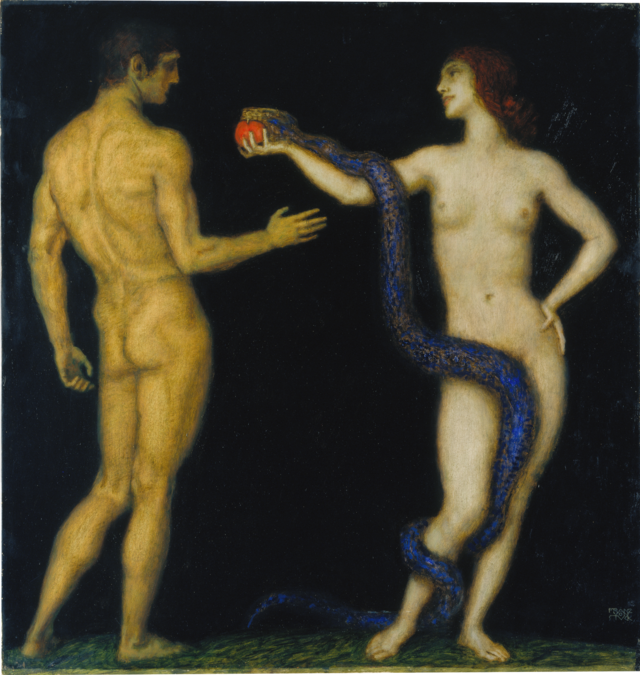

So I have decided to split the difference and spare myself some of the effort by relying initially on two articles by Jesse Hake, to which I provide links below for anyone who might be interested. Then I shall add some notes of my own (which you will find just under the lovely painting by Franz von Stuck reproduced here). Hake has already responded to McDermott in ways that deal quite well with the more substantial slanders in the review.

Alors les voici: ici et ici. (Note how that might also work as a dialogue bubble for the painting.)

Now, I might put some of what these articles say differently, but in essence they get very well to the point. Hake is impressively acute.

I would add only these observations:

A footnote to one of these articles records the estimable Tom Belt’s uncertainty regarding my account of the earliest stratum of the Eden narrative on certain points. Other readers of the book have raised similar questions. But all the evidence one needs is on the page. It is remarkable how we have all been taught to read Genesis through eyes bedazzled by later theological transfigurations of its stories. But my remarks are hardly the result of fancy modern hermeneutics; they record things of which even Church Fathers and ancient rabbis were perfectly aware. I encourage Belt and others to read, for instance, Genesis 3:22-23, and perhaps to supplement it with Genesis 11:6-7. I encourage them also to disabuse themselves of the notion that the original Yahwist myths existed in a world that encompassed the concept of spiritual rather than physical death, or a concept of the gods notably more elevated than what you find in Gilgamesh. The oldest strata of those myths, moreover, are hiding in plain sight in the scriptures as we have them—which perhaps suggests not carelessness on the parts of the Second Temple redactors so much as a sophisticated sense of their people’s religious history.

It is testament only to how slovenly McDermott’s reading of the book was that he could possibly claim it portrays Christian tradition as “bankrupt,” or claim it more or less rejects the Nicene creed. In fact, the book is a defense of tradition—as a living thing to be cultivated rather than as a dead artifact to be curated—and mounts a defense of the creedal formula of Nicaea in particular. Admittedly, I argue for the Nicene synthesis as a synthesis rather than as a digest of some pre-existing, clearly defined orthodox consensus. Newman attempted something along those lines, albeit in the more sophisticated form of a tale of development and emergence; but his arguments fail, as I show in the book, both logically and empirically, principally because he attempted a kind of modern historicist reconstruction of what is, after all, presumably a spiritual history. I therefore propose instead a defense at once more Platonic (in terms of an eternal, analogically grasped essence) and more Aristotelian (in terms of final and formal causality), one that allows us to understand Nicaea as both a terminus ad quem and a terminus a quo, rather than merely as the former. Chiefly I argue that Nicaea was not a reaffirmation of a single prior orthodoxy, but was instead an “inspired” hermeneutical sifting of wheat from chaff and a reformulation of the past in what were novel terms and concepts at the time, guided by a firm if somewhat inchoate sense of the final cause shaping the tradition; and this was possible because, while that antecedent finality (as Blondel would call it) was only adumbrated in the tradition’s past and only imperfectly grasped in its present, it was tacitly recognizable nonetheless. I would blame myself for McDermott’s failure to grasp any of this if it were not the case that so many other readers, from every walk of life, have had no trouble following the argument. Here, let me simply include one of the many, many, many passages in the book that seem to have cunningly eluded McDermott’s notice (those little imps):

For the greatest champions of the Nicene position, such as Athanasius and the Cappadocian fathers, the paramount question seems to have been how such union with the transcendent God was possible for finite creatures. If (to use the familiar formula) “God became human that humans might become God,” could it possibly be the case that the Son or the Spirit was a lesser expression of God or, even worse, merely a creature? It would seem to be a necessity of logic that only God is capable of joining creatures to God; any inferior intermediary, especially one like the created Logos of Arius, will always be infinitely remote from God himself. The Cappadocian arguments against the Eunomians were numerous, complex, and subtle; but at their heart lay a single simple intuition: If it is the Son who joins us to the Father, and only God can join us to God, then the Son must be “capable” of the Father, so to speak. The Son must be God not only in an inferior and secondary sense, but in a wholly consubstantial sense. Moreover, as the argument would play out further at the Council of Constantinople and afterward, if in the sacraments of the church and the life of sanctification it is the Spirit who joins us to the Son, and only God can join us to God, then the Spirit too must be God in this wholly consubstantial sense. In Christ, they believed, God in his fullness really has come to dwell in our midst; and in the Holy Spirit, God in his fullness has really brought us to dwell in Christ.

That said, one cannot really say that the Nicene party’s theological position would have seemed explicitly or obviously more faithful to the past. The prejudice against any suggestion that creation can ever come into direct contact with the transcendent Father was as deeply founded in Christian language and belief as any conviction could be; an immediate presence of the Father to the creature or of the creature to the Father would have been unthinkable in most of the halls of “orthodoxy.” And so it would have been natural for many (perhaps most) of the theologians of the late fourth century to see the union between God and creatures achieved in Christ as merely a kind of inclusion of creatures in the always mediated, structurally subordinationist continuum of divine self-communication: God reaching down to his creatures, but joined to them by the economy of divine diminution. That more radical sense of deification advocated by the defenders of Nicaea was as yet most definitely only one among many possible conceptions of the meaning of the Gospel. It was most definitely an emergent theological model, arising from countless forces and impulses and turns of phrase within the tradition—“let us make them after our own image,” “and God breathed into Adam and Adam became a living soul,” “the Logos became flesh,” “he who has seen me has seen the Father,” “You are gods,” “that they might be one as you and I are one,” “that you might become partakers of the divine nature,” and so on—but it was certainly not foreordained to take the shape it did. On the basis of the testimony of the past, all those forces and impulses and turns of phrase might very well and very convincingly have coalesced into an altogether different dogmatic composite. But when we turn to the great exponents of Nicene theology in the fourth century, what we find in their texts is not merely a catechetical recitation of received wisdom, and certainly not a reliance entirely upon past forms of confession. Yes, they were engaged in a patient practice of critical anamnesis, a discipline of recollection that was also a synthesis of the full testimony of earlier generations of the faith; but that very synthesis and the conceptual and confessional revolution it produced required a standard of judgment that could render the whole tradition intelligible by drawing its various elements into a rational unity and directing them toward a more clearly understood end.

That end, that final cause, was a model of deification adequate both to revelation and to reason. In the case of the former, it did full justice to the very idea of God making himself present in creation as a man. In the case of the latter, it showed that a God whose transcendence is understood in so absolute and so crudely objective a way as to allow no participation, no full communion even with his own divine “Son,” is a God who could never really be present beyond himself at all; only if his very transcendence were already a dynamic relation of full self-expression in his Logos and the full living satiety of Spirit—only if the divine nature really is, as divine, really participable—could he bring creatures into living union with himself. It was the clarifying light of that final causality that made sense of the tradition as a genuine unity. It was the recognition that all those diverse streams of Christian thought and belief regarding the persons of the Trinity and creation and incarnation and glorification in the Age to Come and so forth possessed an intrinsic rationale and meaning that had not yet been clearly stated or ever fully grasped because, until now, its full manifestation had still lain in the future. Once that antecedent finality was grasped—and even then only in part, only as in a glass darkly—it could not fail to be discerned in everything that had gone before. By their openness to what was more than merely the evidence and settled orthodoxies of previous ages, the Nicene party discovered a deeper logic written throughout the tradition they had received, but in a language that had to be deciphered, and for which they only now were able to produce the key. And I wish to be clear here: to the most unforgiving historicist it might seem that the Nicene symbol or the stream of theological tradition that followed from it and thereafter became dominant were merely clever constructs that arbitrarily or accidentally created a new faith out of the old. But here the evidence of history is sufficient to say that what happened in the ascendancy of Nicene orthodoxy can be read as a genuinely rational and even necessary synthesis of the tradition of the past. Even then, however, if the faith inherited by believers in the fourth century possessed a true inner coherence stretching back to its most primordial sources—a coherence that was real and durable and capable of accounting for all its seemingly diverse elements without contradiction or confusion—it was one that could be discovered, manifested, preserved, and confessed only by being reconstructed in light of that more eminent finality: that future, as yet to be fully revealed, but always in the process of being revealed.

(I trust that this is enough to demonstrate how wildly false the picture McDermott paints of the book’s arguments is; but I could adduce quotations from almost every page demonstrating the very same thing.)

McDermott seems shocked—well, actually theatrically contemptuous—at my noting that Arius, in his time and place, could very well be regarded as the champion of a deeply established orthodoxy (especially in the Alexandrian context). That, however, is simple historical fact. That is why there was so large and persistent a resistance to Nicaea even decades after the council, and why the Nicene party was constantly at odds with very eminent bishops and priests and theologians (such as Eunomius). Nicaea was something new, however much it advanced and reformulated things that were also very old. Since this is a matter of the plain historical and textual record, which no good Church historian, of any doctrinal disposition, would deny (not even Newman, however much in his youth he tried to shift the blame to Antioch), it merely shows that McDermott is not particularly learned in early Church history.

McDermott also seems to think that my remarks on the ambiguity of our understanding of “gnosticism” and Marcionism are meant as a kind of simple embrace of what he understands by “gnosticism” over against what he thinks is “orthodoxy.” Readers of Leaves in the Wind are, for the most part, already familiar with my thoughts on these matters, and are aware of how impossible it would be to reduce my views to some crude historical either-or. And, again, I am saying nothing particularly exotic when I assert that, in several respects (cosmology, anthropology, angelology, soteriological narrative), many of those we casually class together as gnostics were closer to the language and vision of Paul or the Fourth Gospel than are many of the later figures of magisterial tradition (Catholic, Protestant, and even Orthodox). This is hardly a controversial claim among those who are (as we have established McDermott is not) deeply familiar with the Christian world of late antiquity. It is also common sense, given that the so-called gnostics inhabited the same spiritual and imaginative world as the authors of the New Testament. All of it is right there to be seen in the pages of scripture (especially if one is reading the actual Greek). And, of course, McDermott does not bother to follow the point I go on to make from there.

McDermott claims that in Tradition and Apocalypse I constantly resort to modern historical-critical scholarship to defend my positions. Now, were this the case, there would be no disgrace in it, since scholarship is a good thing and since current scholarship has an exponentially greater fund of textual and historical resources at its disposal than did the scholarship of a few generations back. But, in fact, most of the historical scholarship I discuss in the book is that of the late eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries, chiefly in regard to the challenges it posed for Newman and Blondel.

McDermott repeats the currently fashionable claim that, in my recent work, I have been moving away from what he and others like him regard as orthodoxy, and that my embrace of universalism was probably the beginning of this tragic dégringolade into damnable heresy. He even tries to draw a connection between that universalism and my supposed apologetics for “gnosticism,” citing as evidence the “magisterial” study of Michael McClymond, The Devil’s Redemption (which is rather like calling the collected works of Rod McKuen a “magisterial” monument of American poetry). Since, however, there are no ancient “gnostic” schools that embraced universalism—in fact, the idea is absurd—and since McClymond’s big book on the subject is widely recognized to be a scholarly catastrophe, this has a rather tinny ring to it. That aside, and for the ten-trillionth time, I have not changed any of my religious leanings in recent years. I was never a champion of the kind of Christianity McDermott believes in. Indeed, I have always been its ardent enemy. I have from the beginning of my intellectual career been a universalist in my understanding of what a coherent Christianity would have to be, and I have always regarded the doctrine of a hell of eternal torment as a barbaric nonsense (which it is). I have also been from the first a metaphysical monist of the Neoplatonic and Vedantic variety, as well as a thinker of a freely and proudly syncretistic bent. And I have never been especially concerned about terms like “orthodoxy” and “heterodoxy” in any narrow or univocal sense, since I have long been aware of how very fluid their acceptations have always been. It would never occur to me to be offended by being called heterodox or to be gratified at being called orthodox. None of this was hidden in my earlier writings.

The distinction the book makes between the modern anthropological category of “religions” (plural) and the ancient and mediaeval concept of religio (singular) as a human virtue goes quite over McDermott’s head. It should not.

Finally, this is something I have been avoiding saying for some years now, but after a relentless series of rhetorically violent attacks on my recent books and willful misrepresentations of my views in the pages of First Things (my explanation for which I will withhold for now), I have lost my patience. Tradition and Apocalypse is, I admit, a provocative book; and it is in fact a somewhat detached one, since it is not a profession of faith, but only an experiment in thinking about tradition in a coherent way (it could have been written by either a believer or unbeliever in exactly the way I wrote it, because I thought dispassion advisable). So criticism is to be expected—but ideally intelligent criticism. Still, the most troubling aspect of McDermott’s review is not its wild inaccuracy or its poor argumentation. It is its tone of absolute hatred. I am a man who enjoys a good exchange of poisoned barbs; but it has to be done with humor and in an honest way. One must not tell lies, or simply blunder blindly over the facts because one is in such haste to attack. One’s polemics must be proportionate to the actual state of affairs. A review in the slanderous and venomous voice of McDermott’s would never have appeared in First Things when Richard John Neuhaus was alive. Whatever you think of the way that suavely thorny individual thought or wrote—I know, sometimes he could seem condescending when he ought not to have done, but no one could accuse him of clumsy viciousness—he was a personally very generous man. When we spoke, he did not fret over our political differences (however much he regretted the “pink flush” in the final pages of The Beauty of the Infinite) and was much more interested in the things we agreed to care about. He even shared my universalist leanings, albeit in a Balthasarian “hopeful universalist” form; more than half our email exchanges over the years concerned just that topic. The last email I ever received from him recorded his “shivers of horror” at having read Garrigou-Lagrange’s book on predestination, and included a link to a review that Nicolai Berdyaev had written of the book when it first appeared. It was possible in his day for me—and others of differing political hues, like Paul Griffiths—to write for the journal in good faith. Moreover, Neuhaus never ceased to be proud of his youthful activism in the company of Martin Luther King Jr. and others, and he would never have embraced the insidious politics of “national conservatism” now pushed like heroin in the pages of the journal he founded, sometimes slyly and sometimes openly, and with room made for only the occasional cosmetic demurral. And, while he enjoyed robust satire and principled polemic, he did not tend to descend to petty screeds and explosions of bile. But that was then. I cannot say that one person in particular is to blame for what has happened to the magazine as it has sunk into the mire of far right traditionalism and nationalism; but, whatever the case, First Things is now to a great degree a journal that feeds and feeds on anger, resentment, hatred, and ever more extreme religious and political views. The tone of the McDermott review is perfectly in keeping with the infantile, carping, petulant, and often cruel tone that has to a large degree become the journal’s house style. The sort of expansive Lutheran-Vatican II Catholic-Evangelical-inter alia Christian comity and hospitality of its former days is very little in evidence, and the genuine concern for a truly Christian social vision (as opposed to mere confessional cultural identity) is more or less entirely absent. The magazine has become something often very sordid indeed: ever more aridly fundamentalist in theology, ever more nastily alt-right in politics. It makes me ashamed to have ever been associated with it. And it makes me grieve for the legacy of a controversial but genuinely decent and deeply thoughtful man, who always tried to be a Christian first.

I have always wondered why Dr. Hart’s positions attract such a fierce criticism from fellow Christians considering that he is, without a shred of doubt, “God-intoxicated” (to borrow Edward Feser’s characterization, which he genuinely meant as a compliment), has vanquished (with his formidable intellect, erudition and writing talents) countless enemies of Christianity, and (as a staunch universalist) believes in the most optimistic apocalyptic horizon. So, what’s not to like?

Surely, some of them disagree with him on purely intellectual grounds, while others are deeply offended by his (sometimes brutal) critiques on the theistic or metaphysic schools (to which they have sworn allegiance) or, in some rare cases, on their mental faculties or education. However, I suspect that most of the attacks (at least those from true believers) come out of fear of divine retribution (which might be exacted on them if they show him even a modicum of tolerance). In that sense, they remind me so much of Job’s friends. And I suspect this because I can recognize that same fear in my own heart. Some of the beliefs Dr. Hart professes (no matter how close to the patristic tradition or how metaphysically sound they are) are simply too frightening to recognize and adopt for Christians taught a much more frightening concept of God. But I really, really hope that his (and Origen’s, Gregory’s and Maximus’s, etc.) theology is the right one, because it is the only one that interprets the Gospel as good news for all of humanity. I can also confidently say that his vision of God is the one that resonates best with my own conscience (which, I would like to believe, is not just a result of operation of cultural forces, but a divine spark). And, lastly, I know that if God were somehow susceptible to flattery, He would find Dr. Hart’s opinion of Him much more complimentary that the one shared by DBH’s critics.

I am among those who only read FT for your articles. As a former (born and raised) Mormon with a doctorate in philosophy and religious thought from Claremont Graduate University, I am in a minority of fellow grad students who didn't retain their original faith or become conventional atheists, and I largely credit your writings and some treasured theological writers I return to from that time as almost the only things that have kept me connected to theology and in that sense to an understanding of God more rational, expansive, and non-provincial than that of my former tradition. Hailing from a framework for God-talk that was thoroughly "radical" or "heretical" (depending on the blasphemic cudgel you happen to prefer), I have no problem with so-called "heterodox" or "radical" theologies, and I have often, from an extremely outsider position, bemusedly and with no small amount of fascination observed the self-appointed warriors of orthodoxy raving like lunatics about your writings, which to me are nearly alone in re-conceiving and re-presenting the Christian tradition in much the same ways that Nicene and other ancient thinkers sought to preserve their history, i.e., in ways that caused that tradition to actually live in and be relevant to the present (including in ways that go well beyond theology proper), instead of being encased behind museum glass that becomes more and more obscure with the passing years.