Graysteil

From the deeper archives...

[Back when I wrote a regular column for a magazine whose name at present eludes me, I occasionally accidentally produced more pieces than were needed for the publication’s ten yearly issues. This was one such column, so it never reached print in… (again, the name is just on the tip of my tongue). Recently I extracted it from my back files in order to revise it for inclusion in a volume of Bentley family chronicles. A version of it did appear in one of my essay collections, but I thought I might make it available here—slightly altered—for those who do not own a copy of that volume.]

Among the more curious relics of my family past is the bronzed left thumb of my agnate ancestor Graysteil Bentley, who lived from 1789 to 1850 and who was the sole proprietor of a small merchant shipping fleet of (at the time of his death) eleven vessels. It is a somewhat ghastly object, principally because the bronzing was so expertly done that every line of the middle joint and the cuticles is perspicuously visible (though, happily, its severed lower knuckle is discreetly concealed in a cap of filigreed silver). It rests under glass on a bed of crimson velvet in a small ebony case, to which is affixed a minute brass plate whose now barely legible inscription reads “Varium et Mutabile Semper Femina.” As a child, I was fascinated and appalled by this macabre vestige of a man long since reduced to dust, but did not think to inquire into the story behind it until I was about fifteen. It was my uncle Robert-the-Bruce Bentley who told me the tale.

At the time of Graysteil’s birth in Baltimore, his family had already made its fortune in shipping. His father’s forebears had settled in St. Mary’s City in 1634, at the founding of Cecilius Calvert’s Maryland colony. His mother was a Scot (hence his rather recherché “Christian” name). Graysteil was, it seems, a precocious and promising lad. He was an avid reader, a lover of poetry, fluent from an early age in French and Spanish (both taught to him by his nurse, a Creole woman from Louisiana), a musician whose virtuosity on the spinet was a great source of pride to his mother, and largely indifferent to the family’s mercantile concerns. His father was occasionally vexed at the boy’s dreamy temperament, but was too indulgent to attempt to alter it.

The family business suffered during the War of 1812, when the entire Bentley fleet was commandeered by the United States government and six ships were lost. But by 1817 the Bentley Line was thriving again and Graysteil’s father, seeking to forge an alliance with a larger shipping firm in Louisiana, sent his son to New Orleans as his liaison. To his delight, Graysteil not only easily ingratiated himself to the firm’s chief proprietor, but within a few months had embarked upon a romance with the latter’s daughter, Lucinde. She was a great beauty, by all accounts, as well as being heiress to a great fortune, and at nineteen never wanted for suitors. She was also a lover of the arts, especially poetry. Graysteil was entirely smitten. In his journals, according to my uncle, he rhapsodized about Lucinde’s “sapphire eyes” and “hair of sable silk” and “alabaster skin,” but was even more ecstatic in his praise of her refinement of nature, the delicacy of her sentiments, and the charm of her conversation. She showed every sign, moreover, of welcoming Graysteil’s attentions.

He had a rival for her affections, however, a wealthy plantation owner bearing the ominous name of Maximillian Ganellon. He was tall, handsome, and rumored to be something of a cad (“Max le malfaisant” he was sometimes called). Unlike Graysteil, he had no interest whatsoever in “higher things”: music and poetry bored him, his conversation rarely strayed away from the secure redoubts of hunting and money, his chief occupation was gambling and his chief diversion (allegedly) women of low degree, and his only conspicuous virtues were his prognathus jaw and broad shoulders. It was inconceivable to Graysteil that the woman who had seized the citadel of his soul could possibly prefer this lissome brute to him. And yet she continued to admit Ganellon into her presence, with every bit as much effervescent gaiety as she accorded Graysteil’s visits.

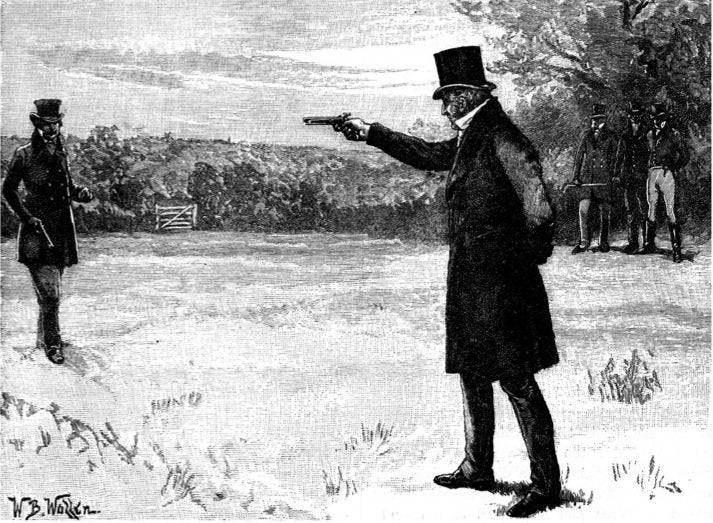

Relations between the two men were poor from the moment of their first meeting, and the sullen suspicion with which each viewed the other soon degenerated into open hostility. Graysteil was somewhat impetuous, it seems, in both his affections and his aversions, while Max Ganellon was a proud and possessive man jealous of everything he considered his by right. Finally, in circumstances of which no precise record remains, one of the men called the other out, and a duel was fought one warm misty dawn just outside the quiet purlieus of New Orleans. Each assumed the correctly oblique posture, confronting the other with as narrow a target as possible; but Graysteil, while holding his left arm folded close against his back, seems to have left his thumb extended behind him. When shots were exchanged, Ganellon missed Graysteil’s chest, but his ball quite by chance amputated Graysteil’s thumb at its base. Graysteil’s shot went entirely wide. The doctor in attendance immediately demanded the duel’s cessation, and all present—antagonists and seconds alike—agreed that honor had been satisfied. Before departing, one of Graysteil’s seconds retrieved his thumb, thinking it a rather indecent object to leave lying in the dust.

With his wound cleaned and dressed by the doctor, faint from pain and shock, and wishing to recover himself properly before venturing out from his rooms again, Graysteil took to his bed for the rest of the day. As he lay there, he resolved to approach Lucinde’s father and seek his consent for their marriage. Surely he had proved the depth of his devotion beyond any doubt. Early in the evening, however, a letter arrived from Lucinde informing him that, having only just learned of the duel late in the morning, she had realized all at once that, while she had felt terrific anxiety for both the combatants, it was the thought of any harm coming to “dear Max” that had pierced her to her core. She knew then that it was he whom she truly loved and that he alone, having won her heart, had any just claim upon her hand. When the doctor arrived next morning to check in upon his patient, he brought the severed thumb with him, washed in spirits and sealed in a green glass phial, not wishing to dispose of it on his own. Graysteil stared at it without words for several moments, and then asked if the doctor knew of any bronze smiths in the city.

Graysteil soon returned to Baltimore, where he began to take a more active role in the running of the Bentley Line. A loss of dexterity in the remaining digits of his left hand caused him to eschew the spinet ever after, and his passion for poetry seems to have cooled considerably. His father died in 1818 and his mother (unexpectedly) in 1821; soon thereafter he appointed his cousin as his agent for running the line and made preparations for a voyage. It was his intention, he said, to immolate himself in the “pyre of the sun.” In fact, he sailed on one of his own ships to the Azores, where he had purchased a house and lands on Pico Island. There he remained for the better part of the next quarter century, pursuing the twin interests of botany (foliate morphology in particular) and seashells. A bit of pernicious family gossip credited him with siring an indeterminate number of illegitimate children on Portuguese women during those years, but no evidence was ever produced to support it.

In 1845, he returned permanently to Baltimore where, within only a few months, he contracted a marriage with a respectable woman more than thirty years his junior who presented him with three healthy sons in four years. He would never see them grow to manhood. One day in June of 1850, while making some kind of an inspection of one of his ships for insurance purposes, he suddenly announced that he intended to scale the rigging. He had never been a sailor, and was hardly a young man, but no one could dissuade him. When he was twenty feet or so aloft, a slight pitching of the ship caused him to lose his footing; and, while his right hand was able to support his weight for a moment, his left could get no grip, and he plummeted to the deck below. Two days later, as he lay dying in his bed, he told his cousin that but for the missing thumb he would not have fallen, and that it was only appropriate that Lucinde’s betrayal would ultimately be the cause of his death.

Anyway, I am not entirely sure what to make of the story of Graysteil’s shattered heart and hand, or of the special significance he attached to the grisly memento that he kept with him to his death, and that he directed be passed on as an inalienable part of his estate as an “admonition to fools who vest their hopes in the fickle heart of woman.” I married young and my twenty-fifth wedding anniversary is rapidly approaching, and the association has left me spiritually content and anatomically intact. Good Confucian that I am, I try to heed the wisdom of my ancestors, but cannot help but think that, where les affaires du cœur were concerned, Graysteil Bentley’s perspective was somewhat distorted. Losing both one’s thumb and the love of one’s life on a single fateful day can do that to one, I would imagine.

I so do regret that socially sanctioned dueling is no longer considered a viable way of settling disputes. It was certainly more civilized than how we handle matters of honor these days. Politics in this country could certainly benefit for reinstating this practice.

A heartbreaking tale. You could have sweetened it by telling us that your ancestor's opponent had met the same end as his famous namesake, but I guess that such a noble reckoning was way out of fashion by then. At least we can find solace in the fact that Graysteil's descendants had much better luck in love.