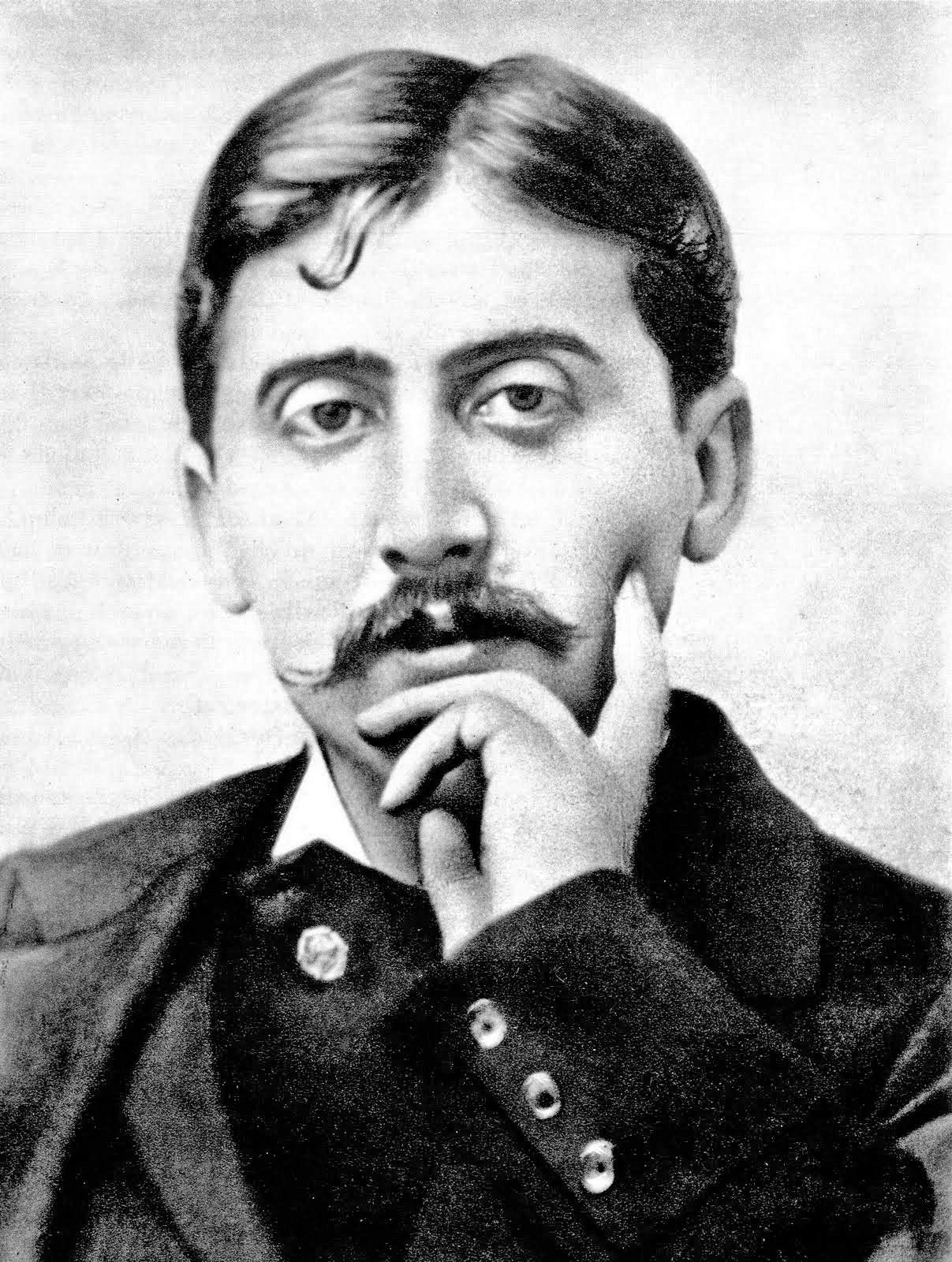

Cher Monsieur Proust,

Je veux vous souhaiter un très joyeux 150e anniversaire, et vous adresser, où que vous soyez en ce moment, mes plus sincères félicitations. Il n'est pas exagéré de dire que vous avez été un écrivain aussi important pour moi qu'Homère, Shakespeare, Lewis Carroll, Kenneth Grahame, Kafka, Nabokov ou Borges. Veuillez donc accepter mes expressions d'admiration et mes meilleurs vœux.

Some day, I expect, I shall write the long essay—or short monograph—on À la recherche du temps perdu that has been incubating in my mind for roughly thirty-seven years; but only God knows when. Today I am writing simply because I feel I owe you a great debt of gratitude, and I did not want to let your 150th birthday pass without telling you as much. Of course, I may be violating one or another sacred prohibition in trying to communicate with the dead, but I assume that, as long as I make no attempt to elicit a reply, no one can accuse me of necromancy. (As to whether I am guilty of a breach of etiquette, I cannot say. But do note that I did not take the liberty of addressing you by your Christian name, as Clive James felt free to do.) In any event, I have no real choice in the matter. When I first truly made your acquaintance—at least, as anything other than a name invested with a tantalizing air of mystery—I was all of 19 but you were already 113 and had been 62 years in your grave.

I was at university in those days, and was living in England; I had not yet made any friends or met the girl who would eventually become my wife; my sole close companion for those first few months were the three large dark silver volumes of Terence Kilmartin’s revision of C.K. Scott Moncrieff’s version of your great work. (I confess that I did not read you in French for another four years.) It was enough. For many nights, over two months or more, I retreated into those pages—and into Combray, or Balbec, or Paris, or Venice, or wherever else the narrative had arrived. Nabokov was absolutely right to describe your book (or its first half, at any rate) as a “fairy tale.” Yes, of course, it is also the consummation of the nineteenth century novel, in its most refined and exquisitely autumnal phase, as well as the first great “introspective” novel of the twentieth century. It is at once an elegy for and a satire on the fading French aristocracy of the Third Republic, as well as a portrait of France’s opulently golden fin-de-siècle twilight and its subsequent slow descent into the starless night of the Great War era. And so on and so forth. But chiefly it is a fabulous journey through a mythic landscape. All of its settings are secret gardens, invisible castles, magic springs, and enchanted woodlands—even the places that putatively exist in the real world. Beginning with that first, outlandish feat of sorcery—conjuring the entire vast architecture of your novel out of a madeleine dipped in lime blossom tea—you are engaged on every page in casting spells: in summoning up strange realms of sensibility, beautiful or mysterious or (on occasion) morbid, but all of them enthralling.

And, of course, the magic at which you most excelled was that of shaping seemingly fully formed characters out of an accumulation of half-formed, sometimes even misleading, partial perspectives and impressions. I think it was Edmund White who noted that, in the portrayal of personality, you possessed all the strengths of the mature Dickens and the late James but none of their weaknesses. Your characters almost always have the vivid, concrete, imperturbably distinct quality of the former’s but never their static completeness, as well as all the subtlety and nuance of the latter’s without ever dissolving (as they repeatedly do) into a mist of tenuous motivations, rarefied sensitivities, precious mannerisms, absurd exactitudes, and exquisite psychological refinements. Your characters are built level by level, by a constant, patient superimposition of transparencies one upon another, some of them mere tissues of rumor, reputation, and misapprehension, others diligently unearthed strata of the hidden past, still others layers of direct observation and acquaintance. The effect is frequently so compellingly convincing that it tempts one to wonder whether real personality is itself anything more than this fluid composite of partial images and apprehensions, a succession of films or membranes of perception, so finely separated from one another that any actual transition from the social to the psychological, or from the objective to the subjective, or from the fictional to the authentic is all but indiscernible.

But that is all far too metaphysical a matter for a birthday greeting. So let me simply note a few aspects of your work for which I am especially grateful, and then leave you in peace. In no particular order, then:

The spire of the church of Combray, glimpsed always at a distance and never quite where it is expected, which is—according to the hour of the day and the angle of vantage—either pink or violet or red or brown or gold. Billowing clouds of white and pink hawthorn blossoms along country paths. Daylight slipping a single luminous “wing” through a parting in the drapes. Bergotte (Anatole France, that is, with a dash of Paul Bourget) rising from his sickbed in order to see the small patch of yellow wall in Vermeer’s “View of Delft” and then suffering his fatal stroke before the canvas. The recurrent musical phrase from Vinteuil’s sonata in its various, ever richer, ever more evocatively unearthly iterations. The long excursus on place-names and the mysterious depths of time that echo up through them. The group of untamed, at times almost feral jeunes filles at Balbec (not your most convincing masquerade, but perhaps your most entertaining). That uncanny thrill I experienced when, in the course of describing Albertine—who reminded me of a girl in high school (let’s call her “Christine”) for whom I had felt a long and hopeless fascination—your narrator mentioned that her beauty mark (which in memory, for a long time, he could not precisely place) was in fact situated on her upper lip—precisely where “Christine’s” was to be found. The final marmorean repose that restores the appearance of youth to the narrator’s grandmother (Sur ce lit funèbre, la mort, comme le sculpteur du Moyen Àge, l’avait couchée sous l’apparence d’une jeune fille). And, of course, the final episode in Le Côté de Guermantes, which may be the most perfectly constructed, most ingeniously choreographed scene in the history of the Western novel: the long disquisition on noble titles, the Comtesse de Molé’s pretentious substitution of used envelopes for calling cards, the flawless set-up for the Duchesse de Guermante’s brilliantly impromptu response to it—above all, Swann informing the Duc and Duchesse that he is dying just when they are preparing to depart for dinner chez Sainte-Euverte and have no time to spare—all of it terminating in the Duc’s hearty, heartless, hilarious, and utterly chilling exhortation: « Et puis vous, ne vous laissez pas frapper par ces bêtises des médecins, que diable! Ce sont des ânes. Vous vous portez comme le Pont-Neuf. Vous nous enterrerez tous ! »

Principally, however, I want to thank you for confirming me in my deepest and most cherished superstitions about the arts. You were a man with no theology (I cannot say whether you still are), and with no precise God as such; but, as you yourself noted, your entire vision of reality had a religious quality to it. One of the most moving passages in À la recherche du temps perdu is one in which you reflect upon the vocation of the true artist—which you characterize as a kind of priestly or vatic rôle, a hieratic mediation between this world and another, higher, purer world. This, at least, is what I wish to believe: that the greatest of artists, far more than philosophers or theologians or saints or prophets, occupy an indispensable station in the Great Chain of Being, there in the Platonic metaxy, intermediate between the realm of the eternal splendors and their shadowy reflections in the world of the senses; that, like the angels, they enjoy at once a cognitio vespertina of reality and a cognitio matutina, and somehow, as even the angels are impotent to do, effortlessly combine the two in their art; and that, like the “great daemon” Eros in the Symposium, they are bearers of oracles and dreams from the “really real” there above to the “land of unlikeness” here below. Your great novel makes me all the more able to believe in a certain ontology, a certain metaphysics, a certain vision of the whole to which I have always been entirely devoted, but of which I need again and again to be reassured. So, for that above all, you have my profoundest gratitude.

En tout cas, j'en ai assez dit. Adieu, Monsieur Proust. Ou plutôt: Adieu, Marcel. (Je n'ai pas pu résister à la familiarité présomptueuse, après tout.) Si l'éternité vous a apporté ne serait-ce qu'une partie du bonheur que vous avez donné à des lecteurs comme moi, alors vous êtes vraiment béni.

Beautiful! I love Proust, he is a portal into the real humanities

This is a wonderful essay. Have you seen Ruiz's excellent, if not great, film, Time Regained?