[I wrote this post when the issue it addresses came up unexpectedly, intending to use it as my weekly offering here. Then, however, it had a sort of advance screening over at Public Orthodoxy, so forgive me if you have already read it. I am posting it now, outside the weekly cycle, because I still want it to be preserved in the archives here at Leaves on the Wind. This version, moreover, is slightly longer than the one that has already appeared.

I want to add that, despite the tone of impatience that is fairly audible in this piece, especially in the later paragraphs, my great affection for and friendship with Matt Levering are still both quite intact. He even encouraged me to give full vent to my annoyance at the treatment he accorded my book in his. My purpose in speaking as candidly as I do here is not to antagonize him—which would be difficult in any event, given his almost saintly character—but to try to wake him from what I regard as his dogmatic slumber.]

“Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.” —Michael Corleone

Let me note, before anything else, that I am not concerned in what follows to defend my orthodoxy, which anyone who cares to may impugn without protest from me. I long ago lost the least interest in how others reckon orthodoxy or heterodoxy, or by what ostensible authority they do so, and am more than happy for guardians at the gate to call me a heretic if it makes them feel better. In many cases, I think the charge a badge of honor. All I ask is that, if I am to be arraigned for heresy, it be for things I actually believe. I mean, I have always felt a certain tender pity for Giordano Bruno, not just because he was murdered by fiends—that will happen now and then—but also because those fiends failed to grasp how much more interestingly offensive they would have found his ideas had they only understood them. Not that I dare compare myself to the glorious Bruno....

Truth be told, I suppose I have little to complain about with regard to how my books have been represented over the years by adverse critics (except of course in the case of That All Shall Be Saved, but there I believe the special problem was the volatility of the topic). For the most part, those who have disliked or disagreed with my views have had no great difficulty in broadly understanding what those views were. Naturally, some readers are always going to be more acute than others, and some will prove quite obtuse; but only a very few are likely to get everything wrong. And so it has been with a book I recently published called Tradition and Apocalypse: until very recently, aside from one absurd review in (predictably enough) First Things, which managed to get everything so wildly backwards that it almost qualified as a burlesque, most of what has been written about the book—approving, disapproving, or something in between—has been decently accurate. Now, however, thanks to an excerpt printed in the Church Life Journal of Notre Dame, I discover that Matthew Levering has chosen to take on my arguments in his recent book on John Henry Newman, and in doing so has oddly conflated my arguments with others that concern him deeply but that are not particularly apposite to my position.

This is not a surprise. I have known Levering for many years and have come to know what to expect him to say on certain issues. But I am not the person he should be arguing with. He is very much concerned with a perceived struggle within Catholic thought between what he sees as an authentically orthodox understanding of doctrinal authority and something that he vaguely denominates “liberalism”. By the former, moreover, he tends to mean an insistence on the reality of a dogmatic deposit that has unfolded with impeccable consistency over the centuries, continuously and smoothly generating firm and cognitively transparent propositional contents, while into the latter category he crowds an outlandishly broad array of differing positions as though they were naturally one (for instance, he treats Loisy and Rahner as having the same understanding of dogmatic authority, which is simply wrong). To me, the very terms of the debate seem curiously antiquated, rather along the lines of trying to determine whether women look more dignified with or without their bustles. More to the point, there seem to be only two categories that Levering recognizes on this issue, and this constitutes something of a problem where I am concerned. My arguments in Tradition and Apocalypse are directly opposed to both options, and so Levering seems not to have a class to place them in.

That said, perhaps I could have made things easier for him. I will admit that my book was an attempt at a subtle negotiation with a particularly intractable problem that has been part of the discourse of theology since it was first identified—but inadequately answered—by Newman: the tension between, on the one hand, the institutional claim that dogmatic pronouncements have always only preserved and reaffirmed established orthodoxy by expressing it in new and clearer formulations and, on the other, the irrefutable evidence of history that, judged solely by their dogmatic and theological antecedents, many such pronouncements look like conceptual disjunctions rather than organic developments. The problem with a subtle negotiation, I suppose, is that it can be too subtle by half for some readers, especially those who prefer a tidily exhaustive conclusion that renders all further negotiations needless. Newman attempted to wrestle the problem into submission by frankly acknowledging the reality of doctrinal development (which is to say, doctrinal change) while attempting to provide a set of criteria by which one might determine the legitimacy or illegitimacy of any given development. As I argue in the book, however, the criteria he proposed are hopelessly circular (something I am hardly the first to note), and this was partly because he was too much bound to the historicist premises he was attempting to refute. My contention, for what it is worth, is that he would have done better to make his case in a more Aristotelian fashion, with specific attention to doctrine’s “final cause” (or, as it is known in the trade, eschatology).

(I also argue that Blondel’s more sophisticated case for the coherency of tradition fails as well, not so much from being circular as from being incessantly “pendulous,” so to speak—oscillating dialectically, that is, between history and experience in a way that cannot be resolved, but from which one can only finally lapse into an exhausted reliance on an infallible magisterium. This too, it seems to me, was an error. One cannot prove the validity of authority simply by invoking that authority as the inviolable limit-condition of one’s questioning.)

Still, I blame Levering rather than myself for the larger misrepresentations, for the simple reason that most of them—apart from quotations removed from any context—consist in claims he places in my mouth, and that in fact flatly contradict what I say in my book. This is because he has drawn my book into a debate in which he has been engaged for years, and as a result has assimilated its position to one to which it simply has no connection. For instance, he weirdly asserts that somewhere I argue that Newman’s account of doctrinal development is “wishful thinking in the service of ecclesiastical conservatism.” And yet this is what I most definitely do not say; in fact, in the book I credit Newman with having the courage and intellectual acuity to address the development of doctrine directly, precisely because he knew that such a retreat into conservatism was a foolish response to the critical challenges of the (chiefly German) theological scholarship of his day. I simply argue that his attempt to meet those challenges failed.

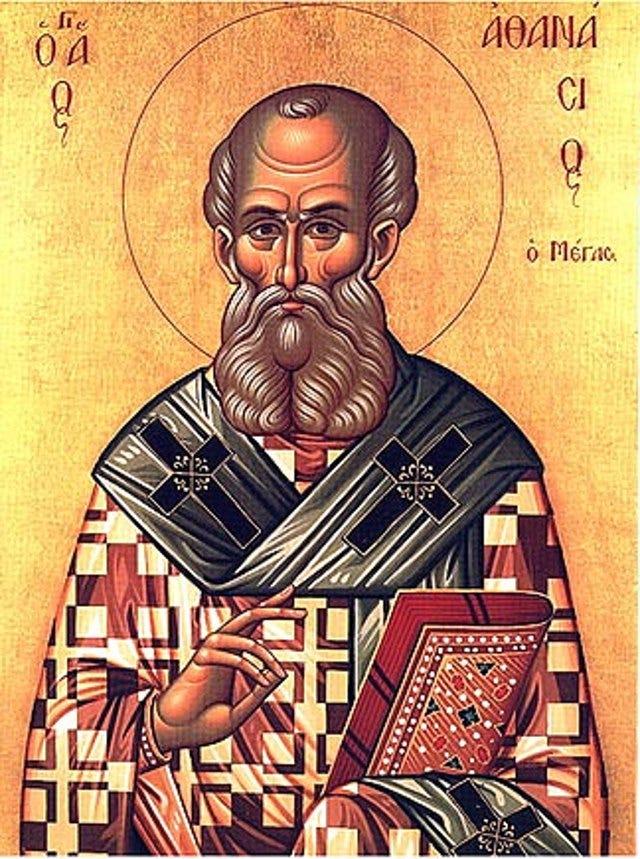

More surprisingly, Levering goes on to claim that it is my judgment that “in reality, there is no doctrinal development of the kind Newman opposes to doctrinal corruption.” I cannot imagine how he arrives at this genuinely bizarre conclusion, since the issue of “corruption” is never addressed anywhere in my book’s pages, while the essential integrity of, say, the Nicene symbol is vigorously defended. He quotes me correctly as observing, in regard to Nicaea, that “the historical record gives no evidence for or against the correctness or incorrectness of any doctrinal synthesis,” which he clearly finds to be a somewhat sinister assertion; yet this is no more than a simple fact about the records of the disputes of the time, and more generally about the nature of all merely historical reconstructions of dogma. That is why Newman wrote his book on doctrinal development, after all. As Levering might have mentioned, though, this observation is not offered as a condemnation of the Nicene position or as some attempt to dilute its validity. In the book, I go on from there to argue that evidences for correctness or incorrectness should never have been looked for solely in such reconstructions in the first place, and that what the history of the Nicene council really reveals is that the rationale for the eventual settlement it reached, and for the very novel “homoousios” formula in particular, rested on a basis more unshakeable than the sort of precedents that the anti-Nicene factions were able to invoke in defense of their views—far more plentifully, in fact, than were their Nicene opponents in defense of the views that eventually triumphed. The Nicene position was premised not simply upon some unambiguous tradition received from the past, but instead upon an established and theologically coherent vision of Christ as the one in whom the transcendent God had truly become human so that humans might truly be joined to him; and only the full divinity of the Son could properly account for this central conviction. In light of this vision, they were then able to render critical judgments upon the past that sorted out and preserved many things that had hitherto been obscure and marginal while displacing many other things from their previous positions of centrality. To be perfectly honest, I am not sure how this marks my argument out as especially “liberal,” even in Levering’s spaciously nebulous understanding of that term.

Inexplicably, moreover, Levering upbraids me for writing that “It would be foolish…to suppose that one could foresee the forms [tradition] might yet assume, the accords it might yet strike, the discoveries it might yet make—both within and beyond itself.” For him, this seems to imply that, in his words, “everything that we think we know in faith (as received and handed on in tradition) might change.” That is a silly and wildly unjustified leap of logic. Of course the church’s understanding of its doctrines, which are minimally formulated for very good reasons, might encourage new paths of thought and new metaphysical and spiritual expressions that as yet we cannot foresee. That has been its entire history, after all. The Catholicism to which Levering is so deeply loyal, for instance, would have been largely incomprehensible to his ancestors in the faith who lived, say, before the sixteenth century, and even more to those who lived before the ninth, and still more to those who lived before the fourth; to the very diverse Christians of the apostolic age, it would have seemed like a completely different faith from theirs, and would have been denounced as heresy by just about every faction. By the same token, the doctrines that the church enunciated over the centuries are nowhere near so concrete or precise as Levering seems to imagine. The Christology of Chalcedon, for instance, has given rise to theologies and systems as diverse as those of Maximus, Scotus, Aquinas, Calvin, and Luther, largely because it is at once propositionally vague and, consequently, speculatively fertile. That does not mean “everything might change.” It does mean that the way Christians understand their faith has changed continuously over the centuries and inevitably will continue to do so in future. This too Newman grasped.

I admit that Levering is correct that I do, in my book, concur with Loisy’s judgment that “Jesus preached the kingdom but the Church arrived,” and even that I observe that it did so in an “often almost comically corrupt and divisive form.” But so have countless historians and New Testament scholars of unquestioned Catholic orthodoxy. So should anyone who knows the New Testament and the record of church history. Moreover, Levering fails to note that, having acknowledged this reality, I then go on to give an entirely different answer to the questions it raises than any that Loisy proposed. I regret that Levering is so disturbed by—I suppose—the apparent irreverence of the observation, but I am fairly sure that the Catholic church in recent years has been more than open to acknowledging frankly the sins of its institutional past (if not, alas, the most egregious sins of the present). This seems like a case of Levering being, as the saying goes, more Catholic than the pope.

Anyway, for Levering, in the end, the damning evidence of my “liberalism” (whatever that may mean) is simply obvious. I condemn myself out of my own mouth.

[For Hart,] tradition is “the constant creative recollection of a promise whose fulfillment and ultimate meaning are yet to be unveiled. Tradition thus must be seen as history’s secret, redemptive rationale.” Hart cautions against smuggling Newmanian doctrinal continuity through the back door. He argues that healthy Tradition “is possible only so long as faith is able to descry a future apocalyptic horizon where the tradition’s ultimate meaning is to be found, and is able also to refuse any reduction of that final revelation to whatever formulations of belief happen to be available at any given stage of doctrinal development.”

The words in quotation marks there are mine, this is true. The interpolated explanations of what I am saying most certainly are not, nor are they remotely related to anything I say in the book. In those genuine fragments of my text, however, I am saying nothing that should offend anyone who does not mistake, say, a formulation as bare and open as the Chalcedonian symbol for a finished revelation of all the mysteries of God’s Kingdom. And I most definitely say nothing remotely like what Levering then imputes to me:

Such a “reduction” prior to the eschaton would assert the ontological truth and irreversibility of all the Church’s solemnly taught doctrines. Preempting such a stance, Hart argues that dogmatic “formulations of belief” are at best “dim prefigurations” that can point us toward the eschaton in which everything will become clear; prior to this end, every formulation is in principle open to rupture and reversal, so long as our trust in the doctrine of the Kingdom does not itself succumb to the solvent.

This is simple balderdash (excuse my strong language). My book certainly says nothing about doctrinal reversal; my emphasis is all upon a future of ever deeper discoveries of the meanings of legitimate developments of dogma, not upon their putative “reversibility.” In fact, the issue never occurred to me, as the book’s central purpose is to make sense of moments of epochal transition in the history of the church. Evidently Levering is failing to distinguish, as I do in the book, between the doctrinal tradition as such and “traditionalist” loyalty to cultural and intellectual habits that have nothing to do with the (again, very minimalistic) language of dogma. What my book cautions against is not “Newmanian doctrinal continuity,” whatever Levering thinks that means, but the attempt to create an impression of historically demonstrable continuities that involves either telling lies about the historical record (which Newman was not willing to do) or inventing vacuous criteria for trying to make the apparent scandal of the historical record disappear.

Of course, yes, I cannot deny that I do indeed believe that the current state of the tradition at any moment in its history should not be mistaken for its sole proper form, and that critical intelligence with regard to the tradition—of the sort exercised by, for instance, the Nicene party in the fourth century—must involve a constant reevaluation of how its past is to be understood in light of the Kingdom it announces, especially when a crisis in the present requires addressing. And thus it always has involved just such a reevaluation. I really do wish Levering had read my chapter on the record of the Nicene council with more diligence and perceptiveness than he apparently did.

Anyway, as the most damning evidence of all of my “liberalism,” Levering adduces a long passage from my book, again entirely severed from any context:

If Christian tradition is a living thing, it is only as tradition—as a “handing over,” a passage through time, a transmission, the impartation of a gift that remains sealed, a giving always deferred toward a future not yet known—that the secret inner presence can be made manifest at all. And that gift must remain sealed until the very end. . . . Once that vital force has moved on to assume new living configurations, the attempt unnaturally to preserve earlier forms can achieve nothing but, at the very best, the perfumed repose of a cadaver bedizened by mortuary cosmetics. True fidelity to whatever is most original and most final in a tradition requires a positive desire for moments of dissolution just as much as for passages of recapitulation and refrain. . . . Even the act of reverently looking back through the past to the tradition’s origin is also an act of critique, a judgment on the past that need not be a kind one, as well as an implicit act of submission to a future verdict that might be equally unkind with regard to the present, and even submission to a final verdict in whose light all the forms the tradition encompasses can be understood as at best provisional intimations of something ineffable and inconceivable. The tradition’s life, it turns out, is an irrepressible apocalyptic ferment within, beckoning believers simultaneously back to an immemorial past and forward to an unimaginable future. The proper moral and spiritual attitude to tradition’s formal expressions, if all of this is correct, would not be a simple clinging to what has been received, but also a relinquishing, even at times of things that had once seemed most precious: Gelassenheit, to use Eckhart’s language, release.

To which Levering witheringly responds, “Loisy could not have said it better.” Well, yes—perhaps not. Neither, however, could Ratzinger have done, nor (in fact) Newman.

I have no objection to the association, I should say, since Loisy—whatever one thinks of his theology—was a great historian who meant well and who was treated abominably. In the Roman Catholic church of today, he would not even be regarded as especially daring in his historical scholarship—but, of course, tempora, mores, and so forth… Even so, I suppose Levering means the remark to be cutting, so let me play along and attempt to parry it. My contention would be that no one who believes that the Kingdom, if it should come, must ultimately infinitely exceed what we can understand about it from the rich but inadequate resources of theological tradition has any reason to be offended by my words. And no one truly familiar with the history of Christian dogma should object to the point I am making in those words. But, as I say, context is everything. What Levering neglects to note is that my remarks at that point in the book are not reflections on doctrinal formulations, which I repeatedly point out are minimally formulated rules that shut down certain broad avenues of thought while opening up others that are often even wider; rather, they are directed at “traditionalism” as opposed to “tradition.” The present-day examples that the book provides of the former are the views of certain Latin-Mass Catholics who believe the pope is a heretic for not reinserting the prayer of Michael Archangel into the liturgy, or certain Orthodox who insist on the myth of an absolutely uniform consensus patrum, or certain Protestants who cling fiercely to a sola scriptura theology that most historically literate Protestantism has outgrown. And the historical examples I provide are such things as the views of those traditionalist theologians of the fourth century who clung to a “subordinationist” trinitarianism, over against the Nicene settlement, both because such subordinationism was in their eyes the established orthodoxy and because they honestly and devoutly believed that it was the only way of properly safeguarding the church’s understanding of the true absolute transcendence of the divine Father. Indeed, they regarded this received picture as central to their Christian confession and to the confession of generations of Christians before them. The Nicene party was, after all, proposing a novel and extra-biblical word—and hence concept—in insisting on a “consubstantial” relation between the Father and the Son. And yet, in time, what had once been regarded by many as central came to be seen as less than marginal, and in fact false; divine transcendence could be asserted, it turned out, and even more radically, in fully co-equalitarian trinitarian categories.

Which makes all the more peculiar Levering’s claim that:

Ultimately, Hart is merely repackaging the familiar notion that there is a fundamental intuition or non-conceptualizable religious experience that is the real core of everything toward which Christians have been striving—the real meaning (if we could only speak it) of everything that the Church’s faltering words seek to express. On this view, Christianity in its essence is a non-expressible religious experience, and “faith is the will to let the past be reborn in the present as more than what until now had been known, and the will to let the present be shaped by a future yet to be revealed.”

This is arrant (and somewhat inexcusably presumptuous) nonsense. What I claim in the book is not that there is some “non-conceptualizable religious experience that is the real core of everything.” As I repeatedly, almost fatiguingly state in the book, the end toward which Christian thought is properly directed is a quite concrete eschatological vision (found, for instance, in 1 Corinthians 15) according to which, in Christ, creation has been truly united to God himself, in a deifying immediacy that no lesser or “secondary god” could achieve. Nowhere—absolutely nowhere—do I suggest that what guides the movement of tradition is some non-conceptual experiential intuition. I say nothing about the experiential side of faith at all, in fact; my emphasis is entirely upon a conceptual horizon that continually generates new formulations. I do call the Kingdom “inconceivable” for us, true, but “inconceivable” and “non-conceptual” are not synonyms.

Finally, there comes this (which I suppose is meant as a rhetorical coup de grâce):

Yet, as always, the theologians proposing this view have dogmas to which they are wedded—in Hart’s case the universal salvation of humans and angels/demons. Hart elsewhere makes clear that anyone who does not believe in this dogma is (objectively speaking) a worshiper of an evil “god” and that any Church that denies this dogma is proclaiming not God but an idol. Liberal theologies are as enmeshed in absolute dogmatic truth as are any other theologies, but on different grounds.

Well, yes, there I must concede the point—not on the “liberal” part or the bit about “dogmatic truth,” but certainly on the matter of the intentionally alarming claim about an evil God. All of that comes from quite another book, of course, and one that (as I say) regularly gets misrepresented; but here Levering is correct. If Christianity is not universalist, I believe, then one can argue that it proclaims an evil God. But, in fact, that is not a “dogmatic” statement on my part. It is a proposition, advanced in that other book’s “First Meditation” by way of a very careful argument (in part, based on a kind of game-theory) regarding what I have elsewhere called the “moral modal collapse” at the eschatological horizon of the distinction between the antecedent and consequent wills of God. If Levering objects, he is free to respond to the argument; the reason for stating my position in so stark a form, after all, was to provoke debate on an issue all too often dealt with inadequately.

Really, though, it scarcely matters. All of this, at end of the day, is just a vapid diatribe; Levering could not bother to follow my arguments, but he certainly seems to have felt a terrific degree of righteous indignation at what he imagined they must be. This is not serious scholarship, it is not responsible or thoughtful argumentation, and at a purely dialectical level it is little better than childish. I know, of course, why Levering chose to draw me into the internal Catholic debate that so concerns him. In Tradition and Apocalypse, I have the temerity to be critical of Newman on the issue of doctrinal development, and Newman’s argument has become over the last century one of the favored weapons wielded by Catholic apologists to fend off whatever questions, legitimate or illegitimate, might be raised by skeptics regarding their tradition. As it happens, even though Levering does not mention it, I also praise Newman, and in fact where I do criticize him it is not for his efforts to defend what he believed was true doctrinal development, but chiefly for being too modern in his assumptions. Even so, Newman’s argument simply does not work, for reasons that are so obvious that it scarcely required my book to call attention to them. I do not mind Levering wanting to engage my treatment of the matter critically; I mind only the misrepresentations. I do not relish seeing my arguments, which I like to think are fairly precise and somewhat delicately calibrated, caricatured in such clumsy terms because Levering insists on reading them through the monochrome spectacles of his stark and simplistic division between a narrow notion of fidelity to Catholic tradition and an impossibly capacious category called “liberalism.” There are far more than only two counterposed perspectives on this matter, even within Catholic circles—indeed, even within “conservative” Catholic circles. If he insists on drawing his picture in crayon, he could at least take a wider assortment of colors out of the box than simply black and white.

Truth be told, the view of doctrine that Levering thinks he needs to defend against the spectre of liberalism at some point becomes both a counsel of willful ignorance and a militant commitment to claims that are objectively falsifiable. And, oddly enough, it is all quite unnecessary. It is perfectly possible to defend the things Levering cherishes—even many that I think drastically mistaken—with far stronger arguments than those Newman came up with in what was, after all, one of his more poorly reasoned texts. In correspondence with Levering since the excerpt from his book appeared, I have discovered that for him the issue is whether or not dogma possesses what he vaguely calls “truth content”; but who is it that he imagines has denied that? Surely dogma can say something true without thereby saying everything. The typical form of any dogmatic pronouncement is a clear but very terse statement of certain rules of theological grammar, as it were; as such, it is specifically designed to invite further and deeper understandings than those that might be evident in the moment. This is scarcely tantamount to saying that there is no such thing as dogmatic truth at all. It really is time to get past this tedious antithesis between fideistic dogmatism and empty emotivism. Both options are idiotic.

I doubt that Levering can be convinced of this. But, frankly, he had better hope that the arguments I make in my book—not the ones he places in my mouth, but the ones really printed on the page—are correct, because they are nothing more than an attempt to make sense of doctrinal history in terms of the actual record (as my chapter on the Nicene Council demonstrates at length). If I am wrong, then Levering has no basis for anything he believes about his faith, because my account of the issue is based on what has actually happened in the course of doctrinal history rather than what one might wish had happened.

All this having been said, I cannot tell a lie: Levering is in fact more right than he realizes. No need to be disingenuous here. I regard the position that he wants to defend over against the oceanic category of “liberalism” as nothing but a nursery fiction, and the effort jealously to preserve it against the banalizing alternative of pure apocalypticism as ultimately an act of bad faith and of scholarly dereliction. That is why my book has the title it has: I am trying to argue that the truth is not an either-or but rather a both-and. So, indeed, my views on dogma probably are far, far more—well, not liberal, which is a fatuous category—but far more radical than Levering would like. I believe he is purveying pious fictions, and I honestly share very few of his beliefs regarding what doctrine is, or what the church is, or even what Christianity is. At present, however, he does not have any idea what my views actually are, so he is in no position to respond to them, much less to deplore them. Perhaps one day, in some context far removed from the internal Catholic debates that render him defensive and me bored, we might discuss them properly. Or not. The opportunity may now have passed irrevocably for both of us, and frankly I am not much interested in the sort of issues that preoccupy him. For now, I ask only to be excused from being associated with a struggle between two positions that I find equally absurd.

Found myself wondering, and by wondering I mean genuinely curious, if Levering’s gross misreading of you, David Bentley Hart—especially since, by your own admission, Levering is someone you heart (pun intended)—might have very well been a deliberate though necessarily unspoken provocation to adequately set you up to bare your Hart (did it again) via your above rebuttal? I.e., perhaps what he would have liked to say about tradition but could not say because of the plausibility if not possibility of authorial, professorial, or overwhelming student/laity disapproval and/or discipline? In other words, well your words to be exact, exactly like you forthrightly admit doing to/for him though for a different purpose: “the reason for stating my position in so stark a form, after all, was to provoke debate on an issue all too often dealt with inadequately.”

David, were you aware of the utterly scathing take on Bruno published with substantive revisions (2019) by the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy?

cf. '7. Religion' in particular ...

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/bruno/