On the Dish Known Vulgarly as Pumpkin Pie

Being a complete and accurate account of the filling, crust, baking, and eating thereof, with many salutary cautions, whereto is subjoined a question on the translation into French of a feeble jest…

…ad maiorem gloriam Dei…

At the request of a number of readers here, I am supplying the pumpkin pie recipe to which I alluded in passing the day before Thanksgiving. After all, some of you reminded me, there are those who might want to make it for Christmas or Hogmanay.

There are various other versions of properly spiced pumpkin pie out there, some even also containing bourbon, and you may wish to look some of them up; but this simple confection has been a constant throughout my life and the lives of my brothers and their assorted offspring. I can attest to its rapturous reception by every guest to whom we have ever served it, with the exception of one peculiarly perverse girl who did not care for the flavor of bourbon at all (a condition for which there is no name and little hope).

The first thing, however, that I must urge is that you set aside any prejudice you may have against tinned ingredients. I have known one or two persons who attempted the madly reckless venture of making pumpkin pie from fresh pumpkins. The problem with this is twofold: For one thing, not all pumpkins are the right kind for making the best pie. For another, the correct process for rendering the common cucurbita orange winter squash into a palatable—or, at any rate, comestible—purée suitable for a sweet dish is an art long vanished from most human memory, having been lost in that vast cultural calamity that we now remember dimly only as ‘The Fall of Night’. Moreover, remember that it is purée that you should be buying, not ‘pie filling’; the tins of these two very different substances are often indistinguishable from one another, so you must pay close attention to the labels.

Above all, you must use a good bourbon. The flavor of the pie varies greatly from one distillation to another. In my experience, none is better than Maker’s Mark for this dish. Its smooth, faintly vanilla finish blends miraculously well with all the other ingredients.

I leave it to you to decide which crust you want to use, only imploring you not to settle for some insipid store-bought frozen pastry. I recommend a good short crust, ideally with some crumbled toasted pecan mixed in.

Now then:

Filling Ingredients:

3 1/2 cups pumpkin purée 2 1/3 cups undiluted evaporated milk 2 cups sugar 1 cup bourbon 2 beaten eggs 4 tsp. cinnamon 2 tsp. ground ginger 1 tsp. nutmeg 1 tsp. salt 1/2 tsp. ground cloves 1/2 tsp. mace

Preparation:

Beat the ingredients together until smooth, pour into pie shells (2-4, depending on the depth you choose, but 3 9-inch deep-dish shells is the typical allotment), and cook by one of the following methods:

Baking:

If you wish to bake your pastry wholly in advance—say, lined with parchment paper, weighted, and cooked for 20-25 minutes at 350˚F.—you can bake the pie at 400˚ with the edges foiled for 25-30 minutes.

If you prefer partially baked crust—say, 10 minutes at 400˚—cook the pie 30-35 at 375˚.

My wife likes a lower temperature and longer cooking time, baking the pie at 325˚ on the lowest rack in the oven for 45 minutes.

The truth is that every oven is different and custard pies are mischievous beings, so just keep an eye on things. You will know when the pie is fully set.

Special Instructions:

It is important to allow the flavors to blend fully, so the pies should be baked a day or two ahead of time—preferably two—and refrigerated. Alternatively, one can mix all of the ingredients other than the eggs two days in advance and refrigerate them, adding the eggs on the morning of the baking day.

Toppings:

In the Midwest and other benighted deserts of the soul, pumpkin pie is often nothing other than a sweet pumpkin blancmange in pastry, served with whipped cream, the latter frequently sweetened as well. This is not food and should never reach your lips. Real pumpkin pie requires no topping at all. If you wish, however, to add a different accent to the dish, gently prick the top of your slice of pie all over with your fork and splash a teaspoon or two of sherry, cognac, or more bourbon on it.

A Variant:

Some members of my family believe the pie tastes better without the mace. I may be one of them. If mace is not to your liking, you may wish to omit it.

Now a quick puzzle for those out there whose French is good and whose wits are nimble. It relates to our competition from some weeks back regarding the rhetorical device (or trick) of the zeugma. There is an old joke out there that comes in various forms, none of them especially amusing, that goes something like this: A man at a bar is nipped on the ankle by a small terrier, which the bartender tells him belongs to the piano player. The man goes to the piano player and says, “Do you know your dog just bit my ankle?” And the piano player replies, “No, but if you hum a few bars, I can wing it.” As I say, not particularly funny. The question I have, however, is whether anyone out there can think of a way of rendering the joke into French so that it is intelligible.

The issue, of course, is that the English verb ‘to know’ functions here faintly zeugmatically. In French, though, this ambiguity is seemingly impossible to reproduce, since the two kinds of knowledge involved correspond to two distinct verbs: savoir and connaître. What the man would ask the piano player would be something like “Vous savez que votre chien vien de me mordre la cheville?” But the piano player would be responding to something like the ungrammatical “Connaissez-vous votre chien vien de me mordre la cheville?” This of course makes no sense.

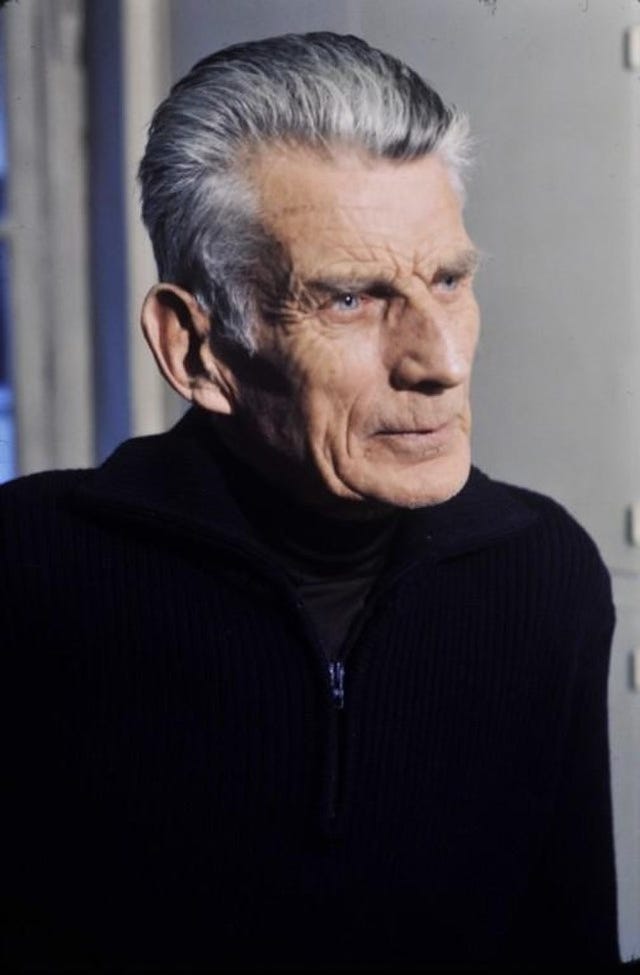

The vexing thing about this, however, is not that the joke is untranslatable, but that in some mysterious way it is. That is to say, we have it on good authority that there is some means of getting around the difference in French between knowing ‘how’ or ‘that’ and knowing ‘of’ something by acquaintance. At least, Samuel Beckett (no less) once claimed that he knew some means of collapsing that opposition into a single equivocal verb, resulting in a zeugmatic duplicity, in French; but then he never got around to saying what it was, and apparently he carried this (Gaul)ling secret to his grave. (Blame Patrick for that wretched pun.) It torments me. For the life of me, I cannot imagine what his solution was. If any of you out there can figure it out, please tell all of us here posthaste. The prize for coming up with the answer is that I will share with you my pumpkin pie recipe.

This translation conundrum could be a case of Beckett's Last Theorem; not space enough in the margin to record it for posterity. Or maybe it's just his own ludic means to keep the critics busy for generations.

Hey David, french fan of yours here, I tried translating the zeugma and came up with that : Un homme, assis à un bar, se fait mordre la cheville par un terrier ; le barman lui explique qu’il appartient au pianiste. L’homme va voir le pianiste et lui dit : « Est-ce que tu mesures ce qui vient de se passer ? » Ce à quoi le pianiste répond : « Non, mais si tu en fredonnes quelques-unes, je peux essayer. »