Q & A 12

The greatest epoch of middlebrow British fiction, the power of prayer, the Shade of Hazel, Kilimanjaro and Koine, Cambridge Platonism, American poets, voices of the gods, pesky devils...

Charme (Duodi), 12 Germinal, CCXXXIII

Christian asks: What is your opinion of Ernest Bramah's works? I ask with a particular curiosity regarding the Kai Lung stories, though I'm interested in your thoughts on his other writings as well.

I have not read Bramah for many years, but I always enjoyed him. The Kai Lung stories were always delightful to me, and the Max Carrados stories too. He was very much one of those British storytellers of the late Victorian and the Edwardian periods—expert at ripping yarns, genial humor, supernatural terror—who created a kind of fantastic milieu that was always enthralling to me at a certain age. Curiously enough, the last gasp of that style of fiction known to me was the first four seasons of Tom Baker’s reign as the Doctor in Doctor Who, when Robert Holmes (that glorious virtuoso of the mustily atmospheric) was the script editor. Bliss was it in that dawn to be a child. Anyway, all the now somewhat quaint ‘orientalism’ aside, Bramah was a greatly entertaining writer.

Christian also asks: What are your thoughts on William Hope Hodgson's Carnacki stories?

In general, Hodgson is less to my taste than Bramah. At his most extreme, he skirts too near the fetid swamps of Lovecraft’s fiction. My most vivid associations with him are the nightmares I got as a boy from The House on the Borderland and The Night Land. But I have fairly good feelings about the Carnacki stories. There one is a little closer to Sheridan Le Fanu territory, in the Dr. Hesselius tales, which I find more hospitable. Algernon Blackwood’s John Silence stories come to mind as well (as Patrick has just reminded me). I do enjoy fusions of detective fiction and tales of the preternatural. Again, all very redolent of a period in British popular fiction that formed a significant part of my sensibility as a boy. And I have to add that, when I think of Carnacki, I see him being portrayed by either Patrick Troughton or Tom Baker.

*******

Sebas asks: Have you ever read Mary Russell Mitford? I just finished her most recognized work, “Our Village,” and found her prose quite exquisite. If you’ve read that book, I’d love to know if you share my judgment.

Alas, I am not entirely in agreement with you. She could write very beautifully, and perhaps I need to give Our Village another look. She could also test the patience of an archangel with some of her gauzy digressions and sentimental meanderings and moralistic ruminations. At her best, she was very very good, but when she was bad she was… trying.

*******

John asks: You have occasionally solicited the prayers of your subscribers in relation to your debilitating medical condition. I recently had an intense discussion with a family member on the power of prayer, me from an RC upbringing and she from a Pentecostal background. As it happens, she is currently battling stage 4 cancer and sincerely believes that the strength of her faith is the only thing standing between her and total recovery. According to your understanding, what are the proper objects of prayer? To what extent and within what scope can prayer influence outcomes?

Well, I certainly do not approve of the notion that prayer only works for those who have ‘sufficient’ faith. That would be a weirdly magical notion both of prayer and of divine grace, though it is one disturbingly prevalent in Pentecostal and Charismatic circles. But I hope and pray that your relative’s cancer goes into remission. As for the proper objects of prayer, I’m not sure I have any special insight there. I assume you mean petitionary prayer, of course, and it seems to me correct to ask for anything, for others or for oneself, that is naturally good: health, relief from suffering, sufficient food, and all the things that Jesus says to rely on the Father to provide. One should never pray, obviously, for things condemned by Christ: things one covets, for instance, such as a neighbor’s house or great personal wealth or the misfortunes of those one dislikes. One caveat here, however, is that it is always virtuous to pray that the Yankees and the Dodgers have bad seasons, as these are things pleasing to God and the godly. Now, as to the extent of prayer’s efficacy or influence, I frankly have no idea. I have never personally experienced any evidence of prayer producing a result I asked for, at least not so immediately as to look miraculous, but there are those I know and trust who have had such experiences—experiences, that is, of even some very remarkable and seemingly impossible events as a result of prayer—and I rely on their testimony that such things occur. Does that mean that prayer has ‘influenced’ events or only that prayer has brought someone into conformity with the course of events that God dictates? I haven’t the foggiest.

*******

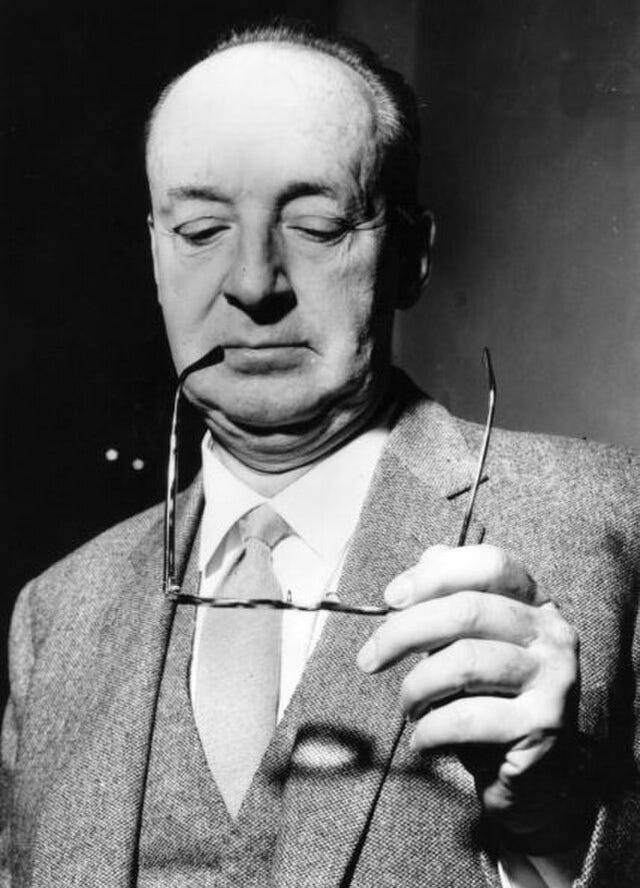

Jigna asks: Is there a specific interpretation of Pale Fire that you favour, specially regarding the question of internal authorship?

Ah, my second favorite topic, coming just after the issue of the many mysteries surrounding Humpty Dumpty’s dialogue with Alice. I can tell you that, in the successive decortication of layers of authorial identity, I stop short of Brian Boyd’s notion that John Shade—still alive and writing—is the author both of the poem and the commentary, and so is the creator of the wholly fictional Charles Kinbote. I have no right to speak for Nabokov, but I think the true answer is the one that the text almost forces you to deduce: that Kinbote is really Vsevolod Botkin, who is genuinely mad and has indeed imagined himself to be the exiled king of Zembla and has genuinely and dementedly confused the poem for an attempt to relate his story in epic form. I think also we are meant to recognize Shade as the poem’s author, to understand that he was indeed killed by a lunatic who mistook him for a judge against whom he was seeking vengeance, and that Kinbote turned the killer into Gradus in his mind. This is mostly because I think the essential story has to do with John Shade and the spirit of his dead daughter Hazel trying to communicate with him. But is there really a single story there? I mean, is there meant to be one definitive answer, or is the ingenious play of mirrors absolute? Maybe Shade is only himself the mad invention of Botkin while Hazel is a mask of his dead daughter Nadezhda. Or maybe Kinbote is the invention of the ghost of Hazel, working through Botkin. And so on and so on. Speaking as someone who willingly goes back into the labyrinth of that utterly magic, absolutely perfect, infuriatingly impenetrable book about once a year, I can honestly say that I am no nearer to finding the Minotaur in his lair than I was at the age of 16, when Pale Fire first appeared in my world and marked my imagination irrevocably.

*******

Peter asks: Have you ever considered translating the Septuagint?

Not really, and for much the same reason that I have not considered trying to scale Kilimanjaro balancing an urn of water on my head: it’s just a little too much trouble. I admit that it is a worthy project (the Septuagint translation, that is, not the Kilimanjaro business). For one thing, the differences from the Masoretic Hebrew text used for most Christian translations of the Old Testament emanate from textual traditions antedating the final Rabbinic version, and for that reason the Septuagint is of considerable historical importance; and it was the Septuagint that constituted the Bible of most Jews and Christians in late antiquity. Understanding the Greek of the Septuagint is essential to understanding the Greek of the New Testament. Then again, so is a knowledge of intra-testamental literature like the book of Enoch. But I am a senior citizen now with books of my own that I want to write before I die, and so I prefer to leave Kilimanjaro and the urn of water to someone younger and with deeper reserves of animal stamina to draw on.

*******

Jason asks: What is your opinion of the Cambridge Platonists? I’m especially curious about figures like Peter Sterry, with his seemingly oxymoronic ‘Puritan universalism,’ as well as the unique style and substance of his overall thought (as cited in Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy, for instance).

I love the Cambridge Platonists. How could I not? Ralph Cudworth in particular. And I have the highest possible regard for Sterry; he almost makes Reformed theology intelligible to me, in the same subversive way as Karl Barth at his best, but with more theological profundity and metaphysical sophistication. Another of that company (Cambridge Platonists, I mean) who deserves more attention than she typically receives, and who was also a universalist, is Anne Conway. Now that I think of it, I should have sneaked some references to her into All Things Are Full of Gods. After all, she is sometimes described as a ‘vitalist monist’, or ‘monistic vitalist’, which tells you a very good deal of why she would appeal to me.

*******

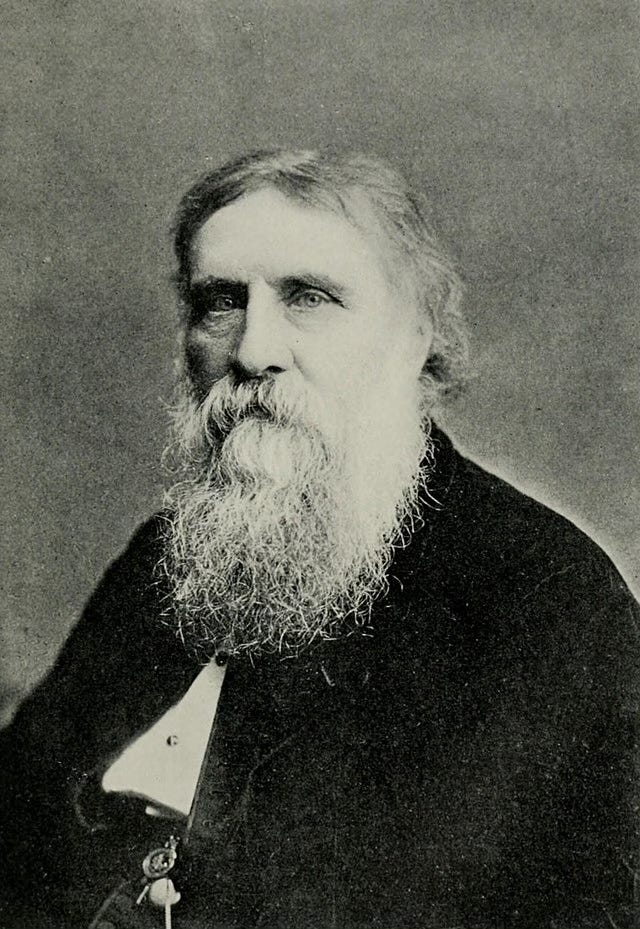

Clayton asks: In his sermon, "The Creation in Christ," George MacDonald argues that a better translation of John 1:3-4 is “All things were made through him, and without him was made not one thing. That which was made in him was life, and the life was the light of men.” In other words, MacDonald shifts the period to before the phrase, “That which was made.” He seems to think this reading is much more interesting and insightful theologically and also that it is supported by the best manuscripts. MacDonald believes that “life” is something created in Christ through Christ's devotion and obedience to his Father, and this devotion and obedience is the light of men. I'm wondering if you think he has a strong argument?

Syntactically, yes, it is a very plausible argument. Metaphysically, however, my first impulse on considering such a revision of the typical pattern of translation would still be to unite that language to the late antique notion of the ‘secondary God’ or ‘Logos’ who is the mediating divine principle through whom cosmic life is created, and only then to extend that language of divine vitality to what it is that the incarnate Logos brings into the world ‘from above’ to those who are ‘from below’. All of that, of course, has to do with my aversion to any theological approach to John’s prologue that might sever it conceptually from a vaguely middle Platonic or Philonian picture of God’s relation to the lower realms of being. For me that is a matter both of historical accuracy and of intellectual honesty.

Clayton also asks: Also, in his sermon, “Abba, Father!” he passionately argues that Greek word usually translated as “adoption” does not mean adoption at all, that since it is, as far as we know, a word that originated in the New Testament, we can only find out its meaning through context, and context makes it clear that it means something very different in the fives verses of the Pauline epistles where the word is used. It seems that something essential about the message of the Gospel is lost when translating huiothesia as adoption, namely God being the very source of our being and having loved us into being as our natural Father.

I am not willing to say that υἱοθεσία definitely does not mean ‘adoption’—literally, ‘installing as a son’—but I grant the force of MacDonald’s argument. Hence some translators prefer, for example, to have Paul speak of ‘a spirit of sonship’ rather than ‘a spirit of adoption’. The word certainly need not be taken as meaning something like the purely forensic convention of legal adoption of a person who has no natural claim to filiation. That said, when the word appears in Romans 8, for example, it does so as part of the prelude of a long discourse that culminates in the image of Gentiles who, being wild olives, are grafted exogenously into the cultivated olives of God’s covenant with the Jews. These may be two separate topics, of course. If I had my druthers, I’d simply say that MacDonald was right, but the truth of the matter is not perfectly clear one way or the other.

*******

WT asks: Do you enjoy Whitman or ‘Song of Myself’?

We walk here on dangerous ground for me. I am something of a heretic when it comes to America’s nineteenth century canon. Not completely, but significantly. I am fully on board with the national pride taken in Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Muir, the James brothers, Henry Adams, Bierce, Twain, and of course (God bless the man) Melville. But I depart from the broad highway of opinion on certain other figures. For instance, granting his gifts as a prose stylist, at least when he wasn’t torturing the English language into something monstrous, I cannot honestly enjoy Poe; and his poetry—absolutely all of it—I abominate. In fact, for the most part, I think American nineteenth century verse is pretty ghastly stuff, almost all of it more or less on the level of William Cullen Bryant and John Greenleaf Whittier (though, oddly enough, I would defend much of Longfellow, especially for young readers, and especially Hiawatha). My two favorite American poets of the nineteenth century are in fact Melville and Jones Very; the former is now much more widely recognized as an important poet than once he was, while the latter is always only just on the verge of being recovered from oblivion. This leaves open the (for me) vexed questions of the two most celebrated American poets of the time: Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman. I have an unfashionably tepid opinion of both, which I usually keep concealed in an inner jacket pocket.

On Dickinson, I see the appeal in her dry morbidity of temper; the quality of the verse, however, often seems not much more impressive than greeting-card jingles, and some of the imagery seems positively ridiculous. To see her compared favorably to, say, Keats or Hopkins, both of whom possessed a mastery of language and imagery far surpassing hers, seems strange to me. I struggle to find many truly strikingly beautiful or haunting lines anywhere in her verse, or any instance of genuine verbal genius. There probably is far more than I can see, and I am just a little obtuse, or a bit like a man from Oregon who can’t quite hear the “melody” in Balinese Gamelan.

So, too, I find that a little Whitman goes a very long way with me. There are some very memorable lines in his poetry, and quite a few of them are found in ‘Song of Myself’, but they are memorable more as souvenirs of a certain very American sensibility and a certain very expansive personality than as specimens of writing I deeply admire. I enjoy it when I am in a certain mood, but to me a lot of it seems quite drab and incontinently gossipy, and some of it is just gushing sentiment. I agree with, I believe, Emerson (if I have that right) who, his initial enthusiasm for Whitman beginning to cool, wrote something along the lines of: ‘I had hoped he would write America’s epic; instead, he seems content only to write its inventories.’

*******

Tim asks: If neither time (as in, the actors don't have to be living) nor budget were a constraint, who would you cast to perform/voice the four characters in All Things Are Full of Gods?

In a comment box attached to this question, one reader opined that I would choose Diana Rigg for Psyche and George C. Scott for Hephaistos. No doubt that was based on what I have written in the past about both of them, specifically in connection with the film The Hospital. I can honestly say that I could think of no better artists for the job. My one alternate off the bench here would be Glynis Johns for Psyche, since she had the most oddly enchanting voice ever granted to living woman by a kindly providence. Anyway, some lovely British woman’s voice in counterpoint to Scott’s rough, irascible, and yet extraordinarily sonorous American voice would be ideal. As for Eros, I am somewhat less certain. I think I might choose Roddy McDowall, just to capture that strange tone of perennial youthfulness, or perhaps Oliver Reed, to capture instead that silky tone of suave salacity; but in the end I think I would have to go with Richard Burton, recorded a few moments after last call. Eros probably does have some Welsh in him. As for Hermes, the choice is so obvious that I probably do not need to say it out loud: Patrick Troughton. No one else was better at snapping off an impatient reply to an irksome question, though he might have to be reminded not to keep addressing Hephaistos as ‘Jamie, you simpleton!’

*******

Michael asks: What are the experiences you have in the past obliquely referred to that convinced you of the existence of malevolent spirits?

Oh, yes… Gosh. I want to be careful here, so as to avoid violating any confidences; I would not want some clever person somehow figuring out what relatives I am talking about in the story and then seeking them out online. Mind you, it was more than 50 years ago. Then too, I do not want to seem like a lunatic or a fool, much less someone who tells tall tales in order to excite interest from the credulous; so I will not wax garrulous or explicit, and will not expand on my remarks here in the comments section. (And, anyway, one doesn’t want to be likened in any way to the revolting Tucker Carlson, who apparently recently claimed to have been assaulted in his bed by a demon. No doubt, if he wasn’t simply lying, he was merely being attacked by his own conscience, to the degree that such a thing exists. If it was a demon, however, I suspect that it was prompted by envy at how much more evil Carlson is than even the most enterprising devil ever could be.) So, here’s the story in summary form, though the names have been omitted and the details largely suppressed:

Back in the early 70’s, relatives on my mother’s side of the family were living in an old and rather rusticated little house a bit off the broad paths, at a time when central Maryland was still largely forested and peaceful. The family consisted of a father with three children who were about my age and younger. The mother was gone and under institutional care, dealing with severe psychological issues that had included, it turned out, some serious dabbling in the diabolistic occult. Anyway, some seemingly malevolent force began to manifest itself fairly unmistakably, in ways physical and audible and seemingly far outside the realm of natural causes. I was present one night when one of these events occurred, trying to go to bed, but not quite making it under the covers on the not unreasonable grounds that it is hard to feel enthusiastic about sleep when the bed is trying to rise from the floor. I really do not want to go through many of the anecdotes, and after half a century my memories are a bit tangled now. Some things one could try to explain away naturalistically, like the appearance of a shocking number of copperhead snakes in the back yard one day or jets of flame leaping from the stovetop at people’s faces at an odd angle; but other things, of a somewhat poltergeisterhaft variety (moving objects, sudden drafts of icy wind, a very distinct and unpleasant voice emanating from an empty room, and some other nasty phenomena), are harder to account for. Even when such things were not immediately perceptible to the human occupants of the house, the little dog there was often able to sense a hostile presence that he bravely wanted to drive away. Anyway, to rush to the conclusion of the tale, the children were removed from the house and came to stay with us chez Hart. A priest (my relatives were Catholic) performed an exorcism of the premises, of an apparently somewhat harrowing sort with some rumored resistance on the part of whatever the presence was, and thereafter the phenomena ceased and the children returned home. You could not have gotten me back in that house for all the tea in China, but they were a hardier breed.

I have no theories about evil spirits, or even about whether actual independent entities were involved. I could just go with theological tradition, I suppose, but that is less illuminating than it initially seems. The dominant strains of Christian lore on the matter differ from the New Testament accounts, and none of it is straightforward. Then, too, one of the children in the household was a girl, and Poltergeist phenomena often occur around children, and around girls in particular; but she was considerably younger than is typical in such cases. It certainly seemed that there was some independent agency at work, but what do I know? I am not a believer in any particular ‘theories’ about demons or powers of darkness; but, sadly, I do not have the option of not believing in something out there, on the other side of the visible order, that is in some sense real and in every sense hostile. Whether the presence in question was a devil, a ghost, or some kind of force summoned out of the psychical distress of one or more members of that family I have no idea. I do not have much interest in such topics, and would rather believe that such things do not exist, but there were simply too many episodes to explain away, at least according to my poor lights. So there. I hope I don’t sound like an imbecile. But I have been in a confessional mood of late, so I might as well risk a little ridicule here. One Orthodox Jewish friend of mine told me that perhaps I should think of whatever that thing was as a dybbuk, which is to say the malicious ghost of some person who had been wicked and who (if I have this right) had been caught betwixt and between embodied lives in the course of the gilgul. If so, a properly posted mezuzah might have had an apotropaic effect, like the blood on the lintels at the first Passover, and might have kept the dybbuk away. For what it is worth, on one occasion the impromptu use of a crucifix seemed to cause one violent manifestation to subside, but I attach no particular conclusions to that. I suspect we are really talking about things that happen in the liminal space between human consciousness (or psychology) and the outer world. Perhaps I should canvass the opinions of Jungian theorists on the matter. Whatever the case, whenever I have flirted with becoming an austere rationalist, like those prophets of Aufklärung for whom I harbor so deep an affection, this is one of the memories that stands as an obstacle in my path that I cannot clamber over. (—And why will you say that I am mad?)

Incidentally, I do realize that today is April (or Germinal) Fool’s Day, but that has nothing to do with this story. I am entirely in earnest.

[Update: My brother Addison has written a reflection now on those events in the 1970’s and on malicious spirits in general over at his Substack page, The Pragmatic Mystic. You can read it here.]

The incidents you refer to that took place in the 1970s are something that directly affected me, given how frequently I stayed there. I was very nearly set alight, in fact, more than once. Since then, I've had a few other such encounters (a few of which I fictionalized in "Patapsco Spirits"). There is no doubt in my mind, at any rate, of the reality of such entities.

Then again—what would the effective difference be between some creature that inhabits the psychic wastes of the imaginal realm as it gathers like turbid shadow around the unconscious of a living soul, conjured by emotions unnameable to children and to the deeply repressed and feeding on their preternatural energies, manifesting in phenomena physical and parapsychological—and a demon?