[And here is the sequel to yesterday’s reprinted column, inspired by those curiously humorless journalists I mentioned. This, incidentally, is the full version of the original column, which has not previously appeared.]

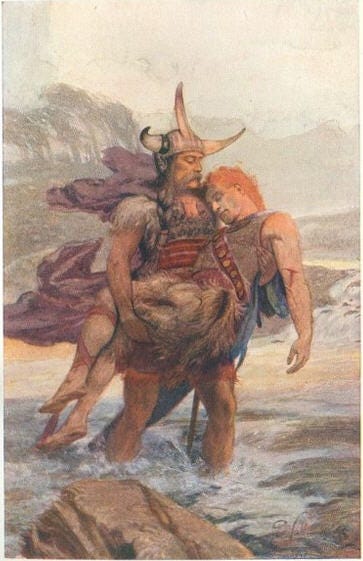

Not to rouse bad memories, but you may recall that my last column contained a list of complaints regarding the misuse of certain words. You may also remember other things about it: Cuchulain battling the sea, mention of “psychotic episodes,” uncongenial dictionaries described as “scented and brilliantined degenerates”… Or perhaps my assertions that grammatical laxity leads to cannibalism, that an unchecked solecism may betray us to the Visigoths or get us eaten by our neighbors, that the use of avocado in sushi is worse than cannibalism….

Well, I assumed the spirit of the piece was obvious. (Dare I call it whimsical? Mercurial? Puckish?) But apparently I was mistaken. One web columnist vehemently denounced me for spreading “fatuous” superstitions about some golden age of correct usage, and condemned my claim regarding bad grammar and cannibalism as “a silly overstatement.” (You don’t say. I stand duly chastened.) Another columnist began by bizarrely describing some etymological argument I had supposedly made about the Latin word parts of “transpire,” which manifestly I had not done, and then proceeded to heap caustic scorn upon my “etymological fallacy.” (Being contemptuously denigrated for an argument one has never made, by the way, is unpleasant. I responded testily to the latter column—called it “dull-witted,” cruelly mentioned endive salad and the superiority of its dialectical skills to those of certain columnists—and then later apologized so as to avoid going to hell. I freely admit it: that guy could acquit himself magnificently against any salad out there.)

Anyway, I’ll take it all as a challenge to clarify or redact my earlier remarks. My column was just an elaborate flippancy, but it did express certain convictions regarding language that I do truly hold, if only with variable earnestness. Most of them require no defense. If you can find a dictionary more than a few years old that, say, allows “reluctant” as a definition of “reticent,” you will also find it was printed somewhere offshore of Singapore under the auspices of “The Happy Luck Goodly Englishing Council.” Moreover, I eschewed artificial grammatical “rules”: no coordinating conjunctions starting sentences, “however” only as a post-positive, “which” only before a non-restrictive relative clause, etc. But I did perversely raise a few genuinely controversial issues, to which I shall shortly return.

The opposition between “precriptivists” and “descriptivists,” let me note, is easy to state in the abstract: The prescriber believes clarity, precision, subtlety, nuance, and poetic richness need to be defended against the leveling drabness of mass culture; the describer believes words are primarily vehicles of communicative intention, whose “proper” connotations are communally determined. The one finds authority in the aristocratic and long-attested, the other finds it in the demotic and current. The one sees language as a precious cultural inheritance, the other sees it as the commonest social coin. The one worries about the continuity of literature, traditions, and the consensus of the learned; the other consults newspapers, daily transactions, and the consent of the people. For one, a word’s proper meaning must often be distinguished from its common use; for the other, they are identical.

In practice, however, no one occupies either position completely. Everyone who cares about such matters engages in both prescription and description, often confusing the two. So does every dictionary. Everyone, moreover, knows words shift in meaning over time. The real question, at the end of the day, is whether any distinction can be recognized, or should be maintained, between creative and destructive mutations. Now, I stand fairly far over on the prescriptive side, for many reasons, but I am not an absolute extremist.

Take my patently subjective preference for the typical British pronunciation of “idyll”—which, incidentally, applies to both syllables. Regarding the initial vowel, the old OED recognizes only the long pronunciation and the The Oxford Dictionary (a different thing altogether) only the short. Good dictionaries now list both. The OED’s editors, however, were classicizing prescribers, swayed not by prevailing practice, but by the syllabic quantities of the Greek “eidyllion.” I, by contrast, defer to the preponderant testimony of generations of English poets and versifiers.

On “intrigue,” however, I take the hard line enunciated in Fowler’s English Usage (the Bible of prescriptivism).

Of “restive,” I was stupid to say simply that it does not mean “restless,” without sufficient elaboration on the point, since “restless” means not merely “constantly moving” or “unresting,” but also “impatient of constraint” or “fidgeting.” Rather, the words are not synonymous. To quote Fowler’s: “Restive implies resistance. A horse may be restless when loose in a field, but can only be restive if it is resisting control. A child can be restless from boredom, but can only be restive if someone is trying to make him do what he does not want.” Thus “restive” can describe a stubbornly inert parliament (Robert Browning), but not Odysseus or Neal Cassady. Restless hearts seek God; restive hearts often reject his call.

Now, regarding “transpire,” I am as inflexible as adamant, as constant as the turning heavens: it does not mean “occur,” no matter how many persons use it that way. This is an old quarrel, true; but its very longevity is instructive. And, curiously enough, it is not only those who reject the “occur” usage in theory, but many who accept it as well, who proscribe or discourage it in practice. Traditionally, there has been a divide between Britain and America here. Scotland’s glorious Chambers, the best one-volume dictionary from the other side of the Atlantic, did not (does not?) admit the “occur” definition at all. The OD traditionally called it “vulgar” or “colloquial” (that is to say, wrong but prevalent). The brothers Fowler regularly abominated it. Webster’s, however, admitted it as a fourth sense in the nineteenth century, while marking it as disputed. American Heritage also used to include it only hesitantly, noting the overwhelming disapproval of its usage panel. The current Merriam-Webster’s, however, claims that the older Webster’s “Sense 4” goes back to the late eighteenth century, and even quotes a 1775 letter by Abigail Adams as proof: “there is nothing new transpired since I wrote you last…”; it notes that the word was popular in nineteenth century journalism, and claims critics began attacking it only around 1870, on etymological grounds; and it says that the usage is now well established in “serious prose.”

Twaddle, alas—and partisan twaddle, at that. Even the Abigail Adams quotation is a blunder: it means not “Nothing has happened,” but only “Nothing new has come out” or “There is no news.” It was principally in nineteenth century journalism that the new definition took hold, and it was attacked as soon as it became common, on many grounds. As for “serious prose,” the best writers now tend to avoid the word altogether. There you have the galling hypocrisy of Sense 4’s educated champions: they discourage it as cumbersomely, ineptly Latinical, but let pass other words of which the same is true, because really they see it as uncouth: vulgar, graceless, fine for the many, unfit for the few. Poor Sense 4: an awkward foundling, admitted into the house of English usage, but denied the love accorded the entitled children. Would it not be more merciful just to drive this pale waif, with his sad opaline eyes and damp ivory brow, out onto the heath? If he cannot be an heir, why condemn him to mere tenancy? Anyway, seriously, Sense 4 is still not universally accepted after two centuries; many of its advocates recognize it only reluctantly and shun it vigorously; and it still strikes sensitive ears as ungainly jargon, even after all this time. For those, like me, who think the distinction valid, its usage as jargon is still not what it really means.

This is an aesthetic prejudice, perhaps, but also a coherent principle. The analytic, lexically antinomian line is that, in themselves, words mean nothing; persons use them as instruments to mean this or that. But, conversely, persons can mean only what they have the words to say, and so the finer our distinctions and more precise our definitions, the more we are able to mean. Hence “prescriptivism,” however hopeless it is, has a rational and moral worth that “descriptivism” lacks. (But the point can be debated without resorting to inflammatory words like “fatuous” or “endive.”)

All of which emboldens me to add: In the present tense, “lie” is intransitive and “lay” is transitive. Coats are “hung” but men are (or used to be) “hanged.” “Aggravate” properly means “exacerbate,” not “exasperate.” “Unique” admits of no comparative or superlative degree. Do not say “enormity” when you mean only “immensity.” And, for God’s sake, do not say “fundament” when you mean “foundation.” Some dictionaries allow such a definition, most do not, and the one definition upon which all agree is something very, very different.

Every time I see the word "fundament" I can only think of Gulliver's Travels:

'I was complaining of a small fit of the colic, upon which my conductor led me into a room where a great physician resided, who was famous for curing that disease, by contrary operations from the same instrument. He had a large pair of bellows, with a long slender muzzle of ivory: this he conveyed eight inches up the anus, and drawing in the wind, he affirmed he could make the guts as lank as a dried bladder. But when the disease was more stubborn and violent, he let in the muzzle while the bellows were full of wind, which he discharged into the body of the patient; then withdrew the instrument to replenish it, clapping his thumb strongly against the orifice of the fundament; and this being repeated three or four times, the adventitious wind would rush out, bringing the noxious along with it, (like water put into a pump), and the patient recovered. I saw him try both experiments upon a dog, but could not discern any effect from the former. After the latter the animal was ready to burst, and made so violent a discharge as was very offensive to me and my companion. The dog died on the spot, and we left the doctor endeavouring to recover him, by the same operation.'

I have a somewhat embarrassing confession to make. When I read Roland in Moonlight you had stated that there were several grammatical mistakes that incite thoughts that border on the homicidal. I misread them at first and congratulated myself. Then I reread the passage, and I’m afraid I have committed every single one of those offenses. I entertained the thought that you were speaking to me through some kind of esp. I half expected you to tell me the color of my t shirt and the couch I was sitting on.

Having said that, reading your work in general has corrected many of my past mistakes. I am immensely grateful for that.