Some Notes and Announcements

Conversations, Gerald McDermott's dishonesty (again), the mad Ed Simon, rules for writers, First Things (again)

1. In months to come—implausibly—I will be recording some conversations with certain friends and acquaintances and posting them here. Mostly writers, but also persons from other (and unexpected) quarters. Not interviews, I hasten to emphasize, but “conversations,” because I do not know how to conduct an interview, and because nearly all of those who have agreed to this scheme have insisted that the interrogations be reciprocal. The recordings should be enjoyable (if only for the spectacle of my incompetence in conducting such things).

2. The writer Ed Simon—anent whom, more below—includes in one of his recent books a chapter on his rules for writers. When I read it, I sent him an email complaining that he had made it impossible for me to write such an essay myself because his perspective and mine were too closely aligned. (Simply said, our shared view of things might be characterized as “Sure, sometimes less is more; but more often less is less and more is more.”) He, however, insisted I go ahead and write such an essay anyway. So, that one too is waiting in the wings.

3. Gerald McDermott, back at First Things, has published an attack on my reply to his attack on Tradition and Apocalypse. I do not know if it is simply an inability to read carefully on his part or instead genuine willful dishonesty, but he begins by citing several supposedly damning quotations from the book that in fact are nothing of the sort. As before, the phrases have all been utterly removed from any context. He presents them as my final judgments rather than—as any competent reader of the book knows—statements either about historical perspectives from the past or about the logical dead-ends toward which Newman’s approach to defending tradition might lead. Thus, for instance, where I lay out how Arians and Eunomians and others in that Alexandrian tradition viewed the Nicene synthesis, McDermott records what I say as if it represented my own personal views of the matter. Thus, too, when I note that, in the fourth century, those opposed to Nicaea could argue that its central synthetic claims encompassed terminology (principally, the word homoousios) that was biblically “unattested,” McDermott casually presents this as a claim on my part that Nicaea was unbiblical in its reasoning (which is, of course, the opposite of what that chapter in the book concludes). And so on. (One hopes McDermott knows that homoousios was a neologism, but who can say?) We live, I know, in an age of fragmentary attention spans, so perhaps McDermott really does not know how to follow a continuous argument across multiple pages, sifting conditional or provisional observations from final judgments. After all, in characterizing my response to his first review, he reveals that he finds certain of the words I used (like “truculent” and “slovenly”) menacingly exotic, which suggests that he suffers from some rather severely arrested reading skills (at least, his vocabulary apparently stopped developing at some point in the fourth grade). Still, as I have noted, of the more than two dozen reviews of the book I have read—positive, negative, lukewarm—only McDermott’s is so bizarrely and systematically inaccurate about its argument. One does not like to think that this is intentional, but the evidence is beginning to tend in that direction. (He also repeats some of his own earlier errors; in defense of the idea of “gnostic universalism” he cites an anomalous and ambiguous sentence from Irenaeus, by way of Michael McClymond, on the Carpocratians—who were not really gnostics, but rather something more like antinomian Orphics—that most scholars do not think means what McDermott imagines it does. What the phrase in question almost certainly means is not that the Carpocratians believed in an eventual salvation of all persons, but only that they believed in one path to salvation for all persons: sic quoque salvari et omnes animas, “and in this way too are any souls to be saved.” McDermott seems to think this is the same as saying et sic omnes animae salvabuntur.)

4. McDermott’s review, I should also note, is pitched at many points in an ad hominem register, full of personal abuse and animadversions on the state of my faith, that would never have passed editorial scrutiny back when First Things actually had editorial standards. I recall David Mills, for instance, drawing a (metaphorical) red line through sentences of mine that only accidentally hinted that I was talking about someone’s character or values. Satire and even sly mockery were permitted, but the rules were pretty inflexible even then. No more. Some readers have noted that, ever since my mysterious parting from First Things (which really is not that mysterious), the magazine has been engaged in a fairly relentless war of abuse against my work. Has any other author ever been honored there with three successive attacks on just one of his or her books, all equally unhinged and rhetorically bellicose? And now McDermott’s review and successor article also seem to indicate a certain recurring pattern. As it happens, when I had finished severing ties with the journal, I intended never to make any public statements on it thereafter. I did, along with other writers who had formally appeared in its pages (Paul Griffiths, Francesca Murphy), sign an open letter criticizing the new “national conservatism” whose advocates included certain members of the senior editorial staff. But I have not until recently spoken about my view of the journal or about the nature of my departure from it. In part, this is because I owe its chief editor a certain debt of gratitude. After the illness that laid me so low in early 2014 and devastated my family’s finances despite my health insurance (God bless America, land of the free), he made it possible for the journal to foot the bill for a long consultation at the Mayo Clinic that, in time, pointed the way toward a substantial recovery (with residual lung damage). It was out of gratitude for this too that I continued my association with First Things far longer than I really felt comfortable doing. But it is now obvious to me that the resentment incurred by my departure is not going to subside, so I think I will have to write an article recounting what happened and why, just to make clear what is going on (and on and on). Unless you, kind readers, advise otherwise. (Comments solicited.)

6. One thing I owe McDermott, however. Since its inauguration a year ago, Leaves in the Wind has attracted far more subscriptions than I had anticipated it would, including a wholly unexpected number of founding memberships. I can now report that there are no great medical debts from my illness from those dark years still hanging over my head, and we have begun to rebuild our savings (so I need not fear dying suddenly as keenly as I did until recently). I could not be more grateful to all of you who have subscribed. Pray God, it continues. But, with the exception of the page’s first two months, I have never had a period in which I acquired so many new subscriptions as I did in the three days following the appearance of McDermott’s review and my reply to it. Maybe the little fracas spread to quarters of the virtual world where the existence of this newsletter was as yet unknown. Maybe there are legions of disaffected former readers of First Things out there eager for any clash of arms of this sort. Who knows? But, if the sudden gush of new paying readers really is connected with that review and my reply to it, I think McDermott may have just bought me a new car (all electric).

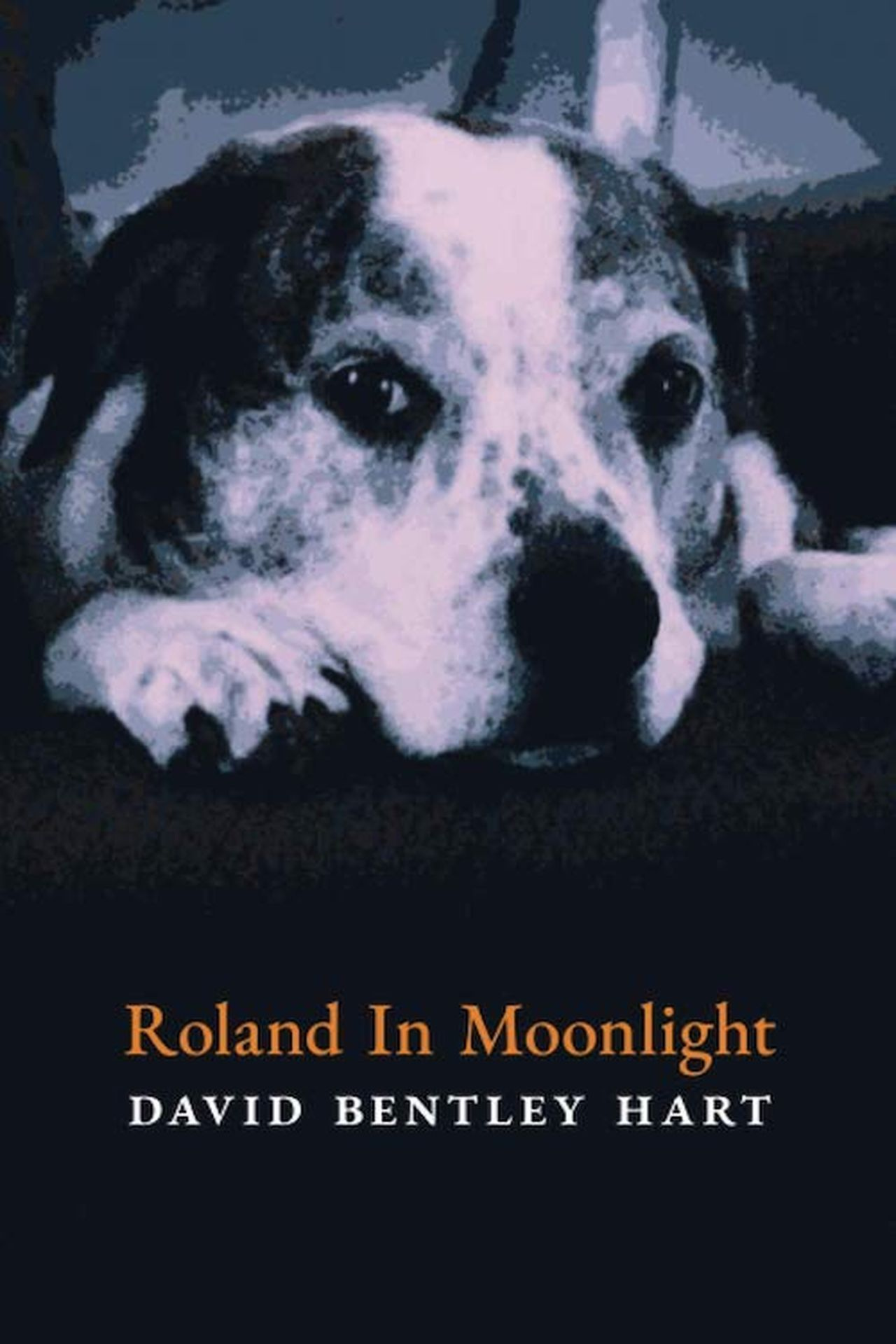

7. Finally, the aforementioned Ed Simon has written a wild and brash review of Roland in Moonlight for the Los Angeles Review of Books. Ed’s take on the book will, I think, throw fuel on the fire among my traditionalist detractors. I think he sees me as an only lightly baptized heathen (which I may be). Whatever the case, it is a review that will make those whose hate I try to attract hate me all the more, and for that I am grateful. And Simon is always great fun to read. My one complaint is that Great Uncle Aloysius and his poetic œuvre get nary a mention, which is a great injustice to the grand old man, whom I still love and revere fervently, despite the disconcerting fact of his never having really existed. (Who then, you ask, is the towering genius who penned the poem “Melancholy”?)

That McDermott's source is not Irenaeus himself but—Michael McClymond! tells you all you need to know about his knowledge of the gnostics. It's like learning about jazz from Adorno. And he claims that you dismiss McClymond's book "without argument," as if you hadn't devoted 4000 words to it—several of them specifically against the claim about the Carpocratians—at Eclectic Orthodoxy three years ago. That said, to give this guy any more attention is straining at a gnat.

I would love to read that story of what happened with FT. Thank you for this update.

Apologies for veering off topic, but I just wanted to mention how grateful I was to encounter your remarks featured over at Eclectic Orthodoxy on Universal Restoration and animals. My dog just received a 6 month prognosis and while my heart grieves mightily, I was comforted by the picture you painted of the personal quality of animals and of their place in the kingdom. Again, please excuse me not adhering to the topics raised in this post, but I wanted to express my gratitude somewhere.