[Here is the second Orlando article from the misty past. By this point, my surgery should be several days behind me, deo volente without complications. As I cannot see the future, however, I cannot yet give any reports on the matter here. Still, prayers, et cetera are as welcome as ever.]

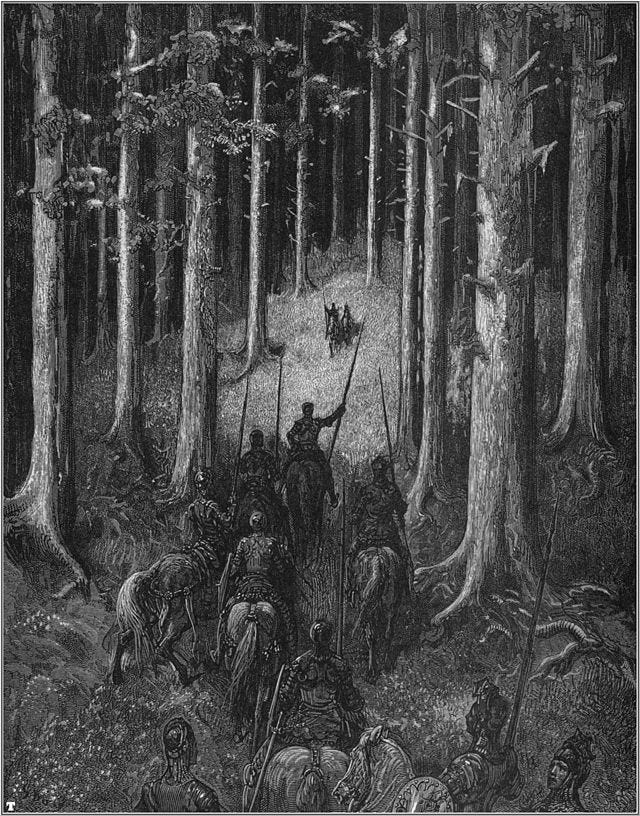

During the high Middle Ages, poems written on the “Matter of France”—that is, tales of the paladins of Charlemagne, and of Count Roland (or Orlando) in particular—were among Europe’s most beloved and most purely fanciful literary entertainments; only stories of the Arthurian court (the “Matter of Britain”) rivaled them in popularity, variety, or extravagance of invention. One would scarcely guess this if one knew only of the Chanson de Roland, the late eleventh century poem from which the whole Carolingian cycle sprang; unlike the earliest Arthurian fables, it was a fairly plain affair, whose atmosphere of austere martial realism was alleviated in only a few places by an incredible detail or two. But, once the Carolingian theme had been stated, the variations that followed from it—in successive chansons de geste and cantares de gesta and Heldengedichte and “epick histories”—departed ever further from the original story’s stern simplicity, and came to incorporate ever more fabulous elements: impossible feats, mythical beasts, magical objects, superhuman foes, and so forth. In the end, the whole tradition culminated in that sudden effusion of glorious literary lunacy that produced the three great Orlando “romances” of the Italian Renaissance—Luigi Pulci’s Morgante (1478-1483), Matteo Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato (finished 1486, published 1494), and Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1516-1532)—which are, without question, among the wildest and most profligate fictions in European literature. They are “epics,” perhaps, but are every bit as defiant of the classical unities (not only of time and place, but of tone and texture) as the dramas of England and Spain’s Golden Age theatres; and they are even more heterogeneous (well, once one excludes Cymbeline from the comparison). Their stories spill across the entire known world, to say nothing of Hell, the realm of fairy, and the moon; they recount sieges, military engagements, and single combat, but also tell of giants, sprites, sorcerers, sea monsters, ogres, magic gardens, and hidden kingdoms; and they lurch convulsively—though somehow quite nimbly—from the hilarious to the sardonic to the violent to the tragic to the mystical. And, once upon a time, they were widely, even avidly read, and their influence pervaded all the literatures of the continent. Certainly, it would be hard to exaggerate their importance for later Italian and French writers (Rabelais is unimaginable without Pulci, for instance); and they may have left their most indelible mark on English letters, from Spenser to Byron and beyond.

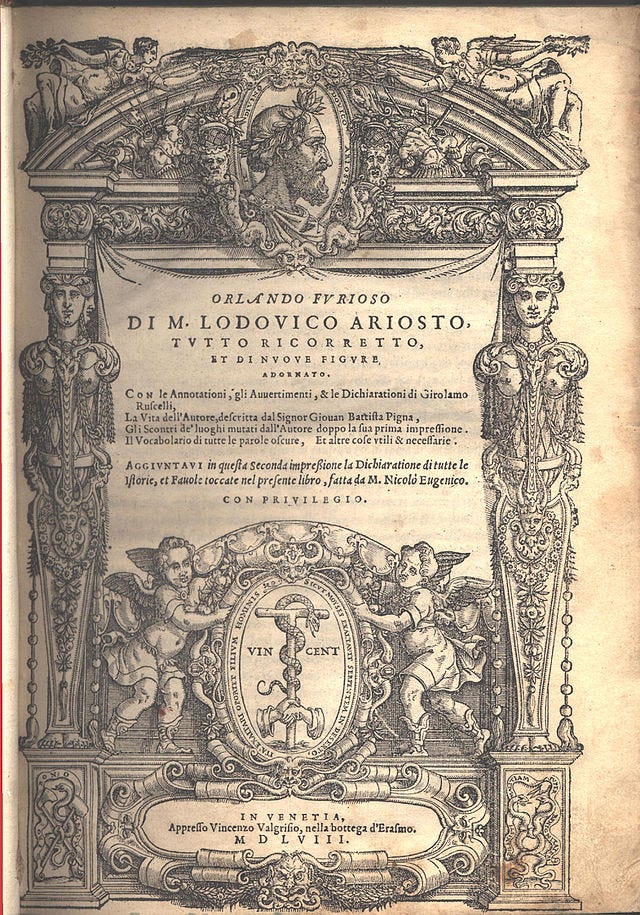

Now, though, they gather dust in those shadowy galleries where the Western canon’s most rarely visited monuments are kept. This is a terrible pity. Modern readers may not have much patience for long verse narratives, but these are anything but forbidding works; they are thoroughly delightful and can be enjoyed by anyone with an imagination and a sense of humor. And yet Pulci and Boiardo, in particular, are scarcely remembered today outside Italy, while Ariosto lingers on in the consciousness of educated persons generally only as an “important” name. There is at least, I suppose, some small justice in this: Ariosto is unquestionably the greatest of the three—the best poet, the most imaginative fantasist, the wittiest humorist, the gravest tragedian—and so, if only one of them is to be allowed any significant posterity, it should be he. And the Furioso is by far the most fully accomplished of the three romances. It retains and improves upon the best aspects of the other two—Morgante’s ribaldry, irreverence, and parody, the Innamorato’s whimsy, brio, eroticism, and fancy—while enlarging the scope of action, enriching the portrayals of individual characters, deepening the pathos of the material, making its levity still more buoyant, and infusing the whole with a greater and more ironic sophistication. Admittedly, exactly what the poem is about is somewhat difficult to pin down; but this hardly matters. The narrative takes up the various stories begun in the Innamorato but left unfinished at the time of Boiardo’s death: the infatuation of Orlando with the beautiful sorceress Angelica, daughter of the King of Cathay, and his pursuit of her across Europe and into the Far East; the siege of Paris by the Moors; the adventures of Ruggiero, mythical founder of the House of Este (of which both Boiardo and Ariosto were clients); the rampages of the evil Moorish King of Sarza, Rodomonte; the wanderings of the English paladin Astolfo; and a number of other plot lines. And the principal pleasure the poem as a whole affords lies in the ingenuity with which Ariosto weaves the disparate tales together in ever more outlandish, intricate, and frenzied complications, and then still at the last manages to resolve them all in a single moment of dramatic finality.

*******

Which brings me, somewhat reluctantly, to the occasion of these observations: Orlando Furioso: A New Verse Translation (2010), by David R. Slavitt. Ariosto’s magnum opus has never wanted for translators, however much reading fashions may have changed over the years. English versions have appeared with a certain predictable regularity ever since John Harington’s splendid edition of 1591. In modern English, there are two faithful and eminently readable translations readily available: Guido Waldman’s in prose, and Barbara Reynolds’s in verse. Now David R. Slavitt has entered the lists with a verse rendering of his own, and… well… What exactly can one say of Slavitt’s version? Clearly it is to his credit that he would undertake so enormous a task, and that he wants to make the book available in what he takes to be a particularly engaging form. But, frankly, there is nothing to recommend this book to any reader interested in Ariosto, or even in a good story. Slavitt makes high claims for his achievement in these pages: he believes (or affects to believe) that he—unlike any of his predecessors, with the possible exception of Harington—has genuinely captured Ariosto’s mercurial “playfulness”; he is even sufficiently pleased with his attempts at an English ottava rima that he does not hesitate (very, very unwisely) to invoke Byron; and he thinks that the exorbitant liberties he takes with the text and the constant intrusions of his own voice into the poem somehow capture the spirit of the original better than a more faithful rendition would. On every count, he is tragically mistaken.

To begin with, it must be pointed out—since one would never know from the book’s cover—that Slavitt’s is an abridgement of the Furioso. It is little more than half the length of Ariosto’s text. Nor is it a prudent, judicious, careful abridgement; it is sheer, haphazard, arbitrary butchery. The first half of the epic is more or less intact; but then it is as if Slavitt simply grew fatigued with the whole project and began hacking off great portions at random. The entire story simply collapses in a heap of disjointed fragments, and all of Ariosto’s mad, elegant narrative choreography is entirely lost. The omissions are simply staggering, and inexcusable. Just as the poem is building to its multiple climaxes, for instance, Slavitt cavalierly skips the last eighty stanzas of Canto 30, then all of Cantos 31 to 33, then the first 39 stanzas of Canto 34, and then all of Canto 35… (and so on). Absolutely crucial episodes disappear altogether (I was especially annoyed to see Astolfo’s visit to Hell discarded), and what remains is incoherent. And then—alas, alack—there is Slavitt’s absolutely ghastly poetry. Charles Ross, in his introduction to the volume, says that Slavitt writes in an “elastic version of iambic pentameter,” which is a nice way of saying that his verse does not scan very well. True, it is pentameter for the most part, but in sprung rhythm—now iambic, now dactylic or anapestic or what have you—with lines of anywhere from ten to fifteen syllables. In principle, this is a problem: the special charm of good ottava rima, as Byron shows, is its combination of aphoristic brevity and humorous digression, which only really works when metric discipline is fairly rigid and the rhymes are particularly clever. Still, though, Slavitt’s dilated periods might be bearable if one did not have to read so many lines twice to hear the stresses, and if his stanzas were not so awkwardly put together; but the syntax is often clumsy, the rhymes are rarely inspired, and the effect is almost always jejune. To take a specimen, more or less at random:

Is it paradise? Or hell? Or is it the place where Love was born? Everybody is dancing, singing, or playing games. There is no trace of snowy-headed Thought. Lascivious glancing seems to be what they do here. In any case, Abundance is everywhere on display, prancing And scattering goodies from its cornucopia In what could easily pass as a utopia. (vi. 73)

“Lascivious glancing/ seems to be what they do here,” forsooth. Could that be more awkwardly phrased? This is simply doggerel, of the most laborious kind (especially that truly execrable concluding couplet).

This makes it all the more irritating that, in his introduction, Slavitt is so condescendingly dismissive of the Barbara Reynolds Furioso; it is not, to his mind, “funny” or “sprightly” enough. In reality, though, Reynolds’s version is superior to Slavitt’s in every way: it is complete, it is more accurate, its versification is more competent, its poetry is usually better, it is more genuinely amusing, and it captures Ariosto’s tone far more faithfully. For example, here is a stanza from the original poem, in which the African soldier Medoro prays to the moon:

—O santa dea, che dagli antiqui nostri debitamente sei detta triforme; ch’in cielo, in terra e ne l’inferno mostri l’alta bellezza tua sotto più forme, e ne le selve, di fere e di mostri vai cacciatrice seguitando l’orme; mostrami ove ’l mio re giaccia fra tanti, che vivendo imitò tuoi studi santi.— (xviii. 184)

Here is the Reynolds translation:

‘O sacred goddess, who in times gone by Hast rightly worshipped been as three in one, Who on the earth, in hell and in the sky In triple loveliness thyself hast shown, Who as a huntress dost in ambush lie Or footprints follow, hear my orison: Show me my king among these many dead, Who in his life by thee was led.’

And here is Slavitt:

“O triple goddess, who in heaven, here, and down in hell you have your different faces, favor us beyond our deserving, appear, and guide us through the horrors of these places. Show us among these corpses where the dear body of our late king lies. Your grace is needful to us now, who bear you love, and pray to you to shine down from above.”

Now, even if one dislikes Reynolds’s (perfectly appropriate) use of an archaic diction to represent the formal language used by Medoro in his prayer, still one must grant that her stanza actually says what Ariosto’s does, using the same imagery, in the same agile measure, and with a certain graceful ingenuity. Slavitt’s, by contrast, departs far from the original in its search for a set of particularly lifeless rhymes—especially that final, forced, embarrassingly leaden couplet—while sacrificing the utterly crucial image of the divine huntress entirely.

And then there is the matter of wit. Here is another stanza from Ariosto:

Quel che fosse dipoi fatto all’oscuro tra Doralice e il figlio d’Agricane, a punto racontar non m’assicuro; sì ch’al giudicio di ciascun rimane. Creder si può che ben d’accordo furo; che si levar più allegri la dimane, e Doralice ringraziò il pastore, che nel suo albergo le avea fatto onore. (xiv. 63)

Here is the Reynolds version of the same:

What in the darkness of the night befell Between the Tartar and the young princess I cannot, I regret, precisely tell, So everyone must be content to guess. I think that they agreed together well For in the morning they arose no less But rather more content; and, turning to Their host, the princess thanked him, as was due.

And here is Slavitt:

And what do you think happened that night between Doralice and Agrican’s son? Do you think…? (Wink, wink! Nudge, nudge! Know what I mean?) I’ll let you imagine what you like. But it’s true that in the morning both of them were seen to be somewhat more cheerful. And calmer, too. She thanked the shepherd for putting them up, and he Said they were welcome, responding most courteously.

It is a matter of taste, of course, whether one finds this obtrusive Monty Python cameo droll (it makes me cringe); but it must be said that, as a matter of simple fact, these sorts of broad vaudevillian antics are utterly alien to Ariosto’s voice. His is a dry, wry, and understated brand of wit, which Reynolds much better approximates (“It think that they agreed together well” is just right).

Anyway, there is no need to go on. Suffice it to say that I come to praise the Furioso, but would dearly love to bury this latest translation (“certain fathoms in the earth”). For those who want to enjoy the book in English, the best choices are still the Harington, Reynolds, and Waldman versions—and I would recommend the Reynolds.