[As I noted in my announcement in my current “Thoughts In and Out of Season” post, little appears here that cannot be found elsewhere—in the preface for the paperback edition of the book or in an earlier post for Leaves in the Wind—but I issue it here in its complete and continuous form, simply because I have been asked to do so by a number of readers.]

Afterword to the Greek Translation

...if the hypothesis were offered us of a world in which...millions [should be] kept permanently happy on the one simple condition that a certain lost soul on the far-off edge of things should lead a life of lonely torture, what except a sceptical and independent sort of emotion can it be which would make us immediately feel, even though an impulse arose within us to clutch at the happiness so offered, how hideous a thing would be its enjoyment when deliberately accepted as the fruit of such a bargain?

—William James

I: The Etiquette of Hell

My friends’ son is now old enough to grant me permission to tell this story, but it happened more than a dozen years ago, when he was only seven or eight. The year before, he had been diagnosed as having Asperger’s syndrome. He was an extremely intelligent child, shy, typically gentle and quiet, but occasionally emotionally volatile—as tends to be the case with many children classified as “on the spectrum.” They are often intensely sensitive to, and largely defenseless against, extreme experiences: crowds, loud noises, overwhelming sensory stimulation of any kind, but also pronounced imaginative, affective, or moral dissonances. So it should have surprised no one when he fell into a state of panic for three days, and then into an extended period of depression, after a Dominican homilist who was visiting his parish happened to mention the eternity of hell in a sermon. But it did in fact surprise his parents, as they had not realized until then that he had never before consciously absorbed the traditional Christian picture of damnation. Now that he had, his reaction was one of despair. All at once, he found himself imprisoned in a universe of absolute horror, and nothing could calm him until his father succeeded in convincing him that the priest had been repeating lies whose only purpose was to terrorize people into submission. This helped him regain his composure, but not his willingness to attend church; if his parents so much as suggested the possibility, he would slip into a narrow space behind the balustrade of the staircase where they could not reach him. And soon they came to see the matter from his perspective. As a result, they have not gone to mass since that time, except as non-communicating guests at a few weddings, and have long since lost any interest in doing so.

Now, to me it seems obvious—if chiefly at an intuitive level—that this story is more than sufficient evidence of the spiritual squalor of the traditional concept of an eternal hell. After all, another description for a “spectrum” child’s “exaggerated” emotional sensitivity might simply be “acute moral intelligence.” As difficult as it sometimes makes the ordinary business of life, it is precisely this lack of any very resilient emotional insulation against the world’s jagged edges that makes that child incapable of the sort of complacent self-delusion that permits most of us to reconcile ourselves serenely to beliefs that should, soberly considered, cause us revulsion. Even if the received Christian view of hell were that of an exclusive preserve for only the very worst of souls—Hitler, Brady and Hindley, Pol Pot—the sheer brutal banality of the idea of everlasting torment would still be morally unintelligible. As it happens, of course, the received view throughout most of Christian history has actually been that hell is the final destination not merely of the monsters among us, but of all sorts of lesser miscreants: the profligate, the wanton, the unbaptized, the unbelieving, the unelect...the unlucky. But this hardly matters. No matter how exclusive we imagine the criteria for membership in the society of the damned to be, nothing can make the idea morally coherent. Choose just one soul, the most depraved you can conceive, and imagine him or her alone subjected to truly eternal suffering, and then try also to make yourself believe that this wretch’s unabating misery, age upon age, is an acceptable price to pay for the existence of the world, for the great drama of creation and redemption, and for the ultimate felicity and glory of God’s Kingdom. If your conscience is a healthy one, you will find it impossible to do so. Or so I would have thought.

I have to confess, however, that since this book first appeared—not quite a year ago, as I write—I have discovered dimensions of religious psychology of which I had formerly been blithely ignorant, or at most only obscurely conscious. This has been, if not necessarily edifying, at least instructive. I knew that I had undertaken to write on a controversial subject, but I had done that in the past, and knew already that to attempt to rouse a true believer (in anything) from what one sees as a dogmatic slumber is to risk waking a sleeping giant instead. Nothing, though, quite prepared me for the passion and, in many instances, vehemence that this text has provoked, at least from its detractors. Those in sympathy with its argument have been gracious in their praise, as such readers tend to be. Some have even exhibited a mastery of its logic that surpasses my own. But the truly hostile readers have behaved in ways unprecedented in my experience. Many of my past writings have inspired strong reactions from the unpersuaded, true, but generally of an emotionally continent kind. The topic of this text, apparently, touches upon deeper springs of disquiet. It has in some cases inspired polemic so shrill, intellectually diffuse, and rhetorically abandoned as to suggest unfathomable psychological sensitivities. As yet, though, it has elicited not a single cogent, interesting, or even vaguely accurate critique. I am not exaggerating. Apart from two honorable but flawed efforts to address the book’s central claims, its adverse reviews have fallen into a strange but remarkably consistent pattern: incensed denunciations of the very idea of such a book, followed by a series of assaults on positions ascribed to me by the reviewer that are in fact eerily unrelated to any claims actually found in the book, followed by a reprise of the denunciations, sprinkled with not a few personal aspersions. I do not mean, I hasten to add, that these reviews have failed adequately to address the text’s assertions. I mean that, to this point, none has even come close to identifying what those assertions are, let alone confuting them. This is very curious. While I am willing to accept some blame for misunderstandings, in the decorously insincere manner expected of any author, I am not willing to grant that the book’s argument—and it is a single, continuous, and necessarily indivisible argument—is really all that difficult to follow. Something else is going on here.

Now, to be fair, some of the book’s critics have also complained about its “tone,” which I cannot say is a first for me. But even this I take chiefly as a reminder of how profoundly our subjective intentions and expectations shape our perceptions of things. On just this issue of authorial voice, anyone comparing the book’s favorable notices to the unfavorable could be forgiven for thinking that two entirely different texts were under discussion. To one camp, the book rings with militant, perhaps occasionally righteously indignant compassion; to the other, it is a wildly belligerent and unprovoked defamation of all those devout souls who meekly cling to a perfectly inoffensive item of Christian orthodoxy. (Obviously, I think the former camp has far better hearing.) Some critics have even wrenched various of my phrases out of context as evidence that the book arraigns traditional believers for moral imbecility or something of the sort, even though not a single sentence in the book condemns any person for anything at all. Mind you, in these pages I do most definitely deprecate ideas I find especially odious, and in resoundingly candid language. But I do so always as a reproach aimed at everyone and no one—at all Christians, Eastern and Western alike, for allowing themselves to be convinced that they are obliged to believe things about God that they would be ashamed to believe about all but the worst of men.

All that said, however, I suppose I do have to plead guilty to a certain breach of etiquette. I knew before setting out that there are some fairly inflexible rules about how one is allowed to discuss this topic, and I chose to ignore them. No one has ever written them down, of course, but everyone is tacitly expected to observe them, and anyone so tactless as to violate them—to raise serious questions in the wrong way about the logical and moral coherence of the concept of a state of perpetual conscious torment visited upon rational creatures by a God of infinite love and justice, or about its scriptural or historical authenticity—risks the sort of censure that can scour a social calendar clean. These rules tell us that one might think the concept of an eternal hell truly obscene, or that it makes existence itself seem like a cruel burden visited on us by a merciless omnipotence, but one must never be so indiscreet as to say so. We must not scandalize the faithful, after all. If one feels an irresistible impulse to raise questions here, one must still conceal any excessive personal distaste for the received view, affect doubt about one’s doubts, assume a deferential attitude toward tradition, and express oneself humbly, hesitantly, demurely, apologetically—even contritely. This, alas, I cannot do. Really, as far as I can see, these rules have nothing to do with good manners and everything to do with uneasy consciences. I am convinced that, just below the surface of most believers’ seemingly equable and settled convictions regarding the reality of an eternal hell, there is a positively volcanic ferment of doubt and repugnance that, if not scrupulously repressed, just might erupt into the open and reduce their faith to ashes. Somewhere deep down, even the most convinced defender of the conventional picture realizes that it is morally absurd, and fears that this absurdity, if frankly confronted, menaces the entire structure of belief.

This is why it is, I imagine, that the understanding of eternal damnation openly espoused in Christian culture has grown gradually but constantly more emollient over the centuries. At one time, in very late antiquity, Western Christians could speak with firm if dour certitude of a place of real physical and mental agony to which the vast majority of the race would be consigned at the end of days, and to which even babies would be sent forever and ever if they were so thoughtless as to die unbaptized. Today only a relatively tiny if obstinate remnant of believers finds that notion tolerable. Already by the high Middle Ages, the roasting babies had been mercifully plucked from the flames and transferred to a “limbo of infants” where, though forever denied the beatific vision, they would nonetheless enjoy perfect natural contentment. And since then, even in regard to unrepentant adult souls, Christians have grown increasingly uncomfortable with the thought that God actively wills eternal suffering, and many have come to adopt the idea that, although hell is eternal, its doors are locked only from the inside (to use C.S. Lewis’s imagery): the damned, that is, freely choose their perdition, out of a hatred of divine love so intense that they prefer endless torment; and so God, out of his fastidious regard for the dignity of human freedom, reluctantly grants them the dereliction they so jealously crave. Needless to say, in this view the fire and brimstone have been quietly replaced by various states of existential unrest and resentfully guarded self-love. It all sounds quite good (unless, as I argue in this book’s Meditation Four, one thinks about it deeply). But it also demonstrates that many Christians know that something is incorrigibly amiss in the very concept of eternal torment, as otherwise they would not feel the need to absolve God of any direct responsibility for its imposition.

Anyway, it is well past time Christians abandoned the etiquette of hell. It has never been anything more than a strategy for sparing themselves the unpleasant task of confronting the real implications of the beliefs they profess. The reason that this topic, more than any other in Christian tradition, has an almost magical power to provoke ungovernable emotions, I am convinced, is that most Christians do not really believe what they believe they believe. I suspect, in fact, that something of the redoubtable Freudian mechanism of “projection” has been at work in the most incensed reactions to this book. Readers who feel that its argument impeaches them for some moral deficiency—to the point of imagining that they clearly recall language in the text that is not actually there—are in all likelihood merely subliminally accusing themselves and then reacting to the sting of their own consciences by accusing this book of unjustly accusing them. They are aware, at some level they rarely plumb within themselves, that they have acquiesced to an irrational and wicked tenet of the creed. They think themselves bound by faith to defend a picture of reality that could not be true, morally or logically, in any possible world, and so naturally they take exception to being made to do so explicitly, rather than implicitly, silently, without any close examination of its contents, or of the degrading compromise of conscience it requires of them. I cannot help that. I remain unrepentant as regards this book’s tone of voice.

And, let us be honest here: does not the burden of proof—and of a certain seemly reticence—fall quite on the other side of this debate? After all, why should anyone feel the need to apologize for condemning an idea that looks fairly monstrous from any angle, and whose principal use down the centuries has been the psychological abuse and terrorization of children? Who, after all, is saying something more objectively atrocious, or more aggressively perverse? The person who claims that every newborn infant enters the world justly under the threat of eternal torment, and that a good God imposes or permits the imposition of a state of perpetual agony on finite, created rational beings as part of the mystery of his love or sovereignty or justice (or whatever else)? Or the person who frankly observes that such ideas are cruel and barbarous and depraved? Which of these two should really be, if not ashamed of his or her words, at least hesitant, ambivalent, and even a little penitent in uttering them? And which has a better right to moral outrage at what the other has said? And, really, do these questions not answer themselves? A belief does not merit unconditional reverence just because it is old or because its proponents claim a divine authority for it that they cannot prove; neither should it be immune to being challenged in terms commensurate to the scandal it poses. And the belief that a God of infinite intellect, justice, love, and power would condemn rational beings to a state of endless suffering, or would allow them to condemn themselves on account of their own delusion, pain, and anger, is probably worse than merely scandalous. It may be the single most horrid notion the religious imagination has ever entertained, and the most irrational and spiritually corrosive picture of existence possible. And anyone who thinks such language too strong or caustic, while at the same time finding the traditional picture of a hell unobjectionable, needs to think again. If anything, my rhetoric in this book is probably far, far too mild.

Which brings me back to the story with which I began.

Since this book first appeared, I have in a variety of venues stated that to my mind its argument is irrefutable, and that anyone who remains unpersuaded by it has simply failed to understand it. Obviously an assertion meant to provoke, and one that probably reflects a certain temperamental fatigue on my part. But I also happen to believe that it is true. I am not, however, claiming that the book is a unique work of genius, even if I do take a certain pride in the construction of its argument. Rather, I believe that many of the truths it points out are fairly obvious. I do not actually think it an especially rare accomplishment to be irrefutable on this topic. Some of the books I mention in my postscript, for example, as well as many that I do not, all seem every bit as logically unassailable to me. But I think my friends’ child’s natural reaction to that sermon was also an irrefutable argument. In truth, the notion of eternal torment it is so unquestionably, resplendently warped and irrational that every defense of it ever made, throughout the whole of Christian history, has been a bad one. We may deceive ourselves that we have heard good arguments in its favor, but only because we have already made the existential decision to believe in hell’s eternity no matter what—or, really, because that decision was made for us before we were old enough to think for ourselves. Even many otherwise competent philosophers have, under the impulse of faith, convinced themselves and others of the solvency of arguments that, viewed dispassionately, scarcely rise to the level of pious gibberish. It has always all been a mirage. If, however, one can make oneself retract that initial surrender to the abysmally ludicrous, for only a moment, one will discover that all apologetics for the infernalist orthodoxy consist in claims that no truly rational person should take seriously. Every one of them is an exercise in self-delusion, self-hypnosis, pacification of the conscience, stupefaction of the moral intelligence—and nothing else.

I think that all of us, with a few lamentable pathological exceptions, are aware of the preposterousness of the idea of an eternal hell, and that most of us have realized as much at various times in our lives, in moments when we have inadvertently allowed our moral imaginations to slip free from their tethers of pious dread. In those instants, the doubts come flowing in like a tidal wave. We suddenly realize that, were the dominant tradition true, all of existence would be a kind of horror story, like a tale of guests at a party at a splendid estate enjoying themselves in perfect ease of mind while far below, down in the deepest basement of the house, there lies a torture-chamber filled with victims who cannot escape and whose cries never reach the rooms overhead. But then, devout and obedient souls that we are, we regain control of our thoughts, drive those doubts away, and try to forget as quickly as possible what our consciences are telling us (lest God overhear them and damn us forever). Still, it is obvious. There is an argument against the coherence of the doctrine of eternal perdition that is simpler than any other and that is incontrovertibly true and that I think all of us know without realizing we know it. It is not one that appears explicitly in the text below, though it is arguably implicitly present throughout. And, while most infernalists would dismiss it as trivial or impressionistic or sentimental, its logic is devastating for anyone willing to set his or her heart to contemplate it. It is this: The irresoluble contradiction at the very core of the now dominant understanding of Christian confession is that the faith commands us to love God with all our heart, soul, and mind and our neighbors as ourselves, while also enjoining us to believe in the reality of an eternal hell; we cannot possibly do both of these things at once. I say this not just because I think it emotionally impossible fully to love a God capable of consigning any creature to everlasting suffering (though in fact I do think this). I say it, rather, because absolute love of neighbor and a perfectly convinced belief in hell are antithetical to one another in principle, and because all our language of Christian love is rendered vacuous to the precise degree that we truly believe in eternal perdition. Love my neighbor all I may, if I believe hell is real and also eternal I cannot love him as myself. My conviction that there is such a hell to which one of us might go while the other enters into the Kingdom of God means that I must be willing to abandon him—indeed, abandon everyone—to a fate of total misery while yet continuing to assume that, having done so, I shall be able to enjoy perfect eternal bliss. I must already proleptically, without the least hesitation or regret, have surrendered him to endless pain. I must—must—preserve a place in my heart, and that the deepest and most enduring part, where I have already turned away from him with a callous self-interest so vast as to be indistinguishable from utter malevolence.

The very thought sometimes tempts one to wonder whether Nietzsche was right, and all of Christianity’s talk of charity and selfless love and compassion is mostly a pusillanimous charade, dissembling a deep and abiding vengefulness. As I say, the committed infernalist will wave the argument off impatiently (before it has a chance to sink in). But I think an honest interrogation of our consciences, if we allow ourselves to risk it, tells us that this is a contradiction that cannot be conjured away with yet another flourish of specious reasoning and bad dialectics. Can we truly love any person (let alone love that person as ourselves) if we are obliged, as the price and proof of our faith, to contemplate that person consigned to eternal suffering while we ourselves possess imperturbable, unclouded, unconditional, and everlasting happiness? Only a fool would believe it. But what has become the dominant picture of Christian faith tells us we must believe it, and must therefore become fools. It demands that we ignore the contradiction altogether. It also demands that we become—at a deep and enduring level—resolutely and complacently cruel.

II: A Few Clarifications

As I have said, as of yet no solvent criticisms of this book’s argument have yet appeared; but there have been a number of adverse reviews in which entirely different arguments, easier to counter, have been attacked in its place. I have seen this book’s Meditation One, for instance, characterized as a specimen of theodicy—that is, an inquiry into why God permits evil things to happen—though in fact it is nothing of the sort. Similarly, I have seen Meditation Two described as an attempt to argue that the New Testament is uniformly universalist in theology, which it is not. The Third Meditation has been presented as having something to do with the question of whether the saved can be happy in heaven if others are damned, which is a fatuous question and one that could not be further from my real concerns. And as for Meditation Four, the poor thing, it has been the victim of the wildest misconstruals of all: I have seen it described as an argument for determinism, or as some new and outlandish theory of human free will, or as an argument to the effect that our free will must be “overwhelmed” by God’s. So, while I have not had to struggle with serious challenges to my views, I have been obliged to restate them repeatedly.

At times, this has been easy enough, if not necessarily effectual. It takes little effort, for example, to explain that the issue of Meditation Three is not whether we can be happy in heaven in the absence of certain other persons. A heroin addict is happy when high, after all, no matter what his circumambient conditions, and no doubt God could preserve us in an opiate ecstasy forever if he so chose. The issue is at what price that happiness is to be purchased, and whether we can actually be saved as the persons we are—or as persons at all—under those terms. (We cannot, incidentally.)

Again, in the case of Meditation Two, the basic issues are quite simple. There the difficulty lies in convincing readers to relinquish their certitudes regarding what they imagine they know about the text of scripture, as a result of long indoctrination (fortified in most cases by misleading translations). I have, for example, repeatedly seen readers claim with considerable assurance that the Christ of the synoptic gospels spoke of a place called “Hell” where souls suffer eternal torment through the application of unquenchable fire and the tender ministrations of an immortal worm. In fact, Christ spoke of a place called the Valley of Hinnom (Gehenna) which lay outside Jerusalem, and which had become a rather nebulous image in his time of God’s judgment both within and beyond history; and he described that valley in terms borrowed from Isaiah, as a place where corpses would be consumed by flames that were always burning and by worms that were always devouring carrion. It is an image of the final disposal and destruction of the dead, not of their perpetual suffering. And, given that Jesus told his followers that in many instances he was speaking of things that would occur within their lifetimes, it is also clear that much of that imagery applies to intra-historical calamities, not just to some final judgment at history’s end. Then, too, Jesus used a whole host of other images of judgment as well that, read literally, are not compatible with one another, and certainly provide no simple uniform theology of the afterlife; some, in fact, clearly suggest an eventual deliverance from “final” punishment. But, no matter the imagery he employed, absolutely nowhere did he describe a place of eternal misery.

In general, in fact, New Testament scholars are keenly aware that neither Jesus nor Paul advanced a picture of eternal torment like that of later Christian teaching. Where that later language came from—appearing as it did roughly a generation after the time of the apostles—is a matter of some debate. The historian Dimitris Kyrtatas, for instance, attributes much of it to the apocryphal Apocalypse of Peter. Whatever the case, though, the critical consensus is that the New Testament contains, for the most part, two kinds of language about the last judgment: one that seems to portend the final destruction of the wicked at the threshold of the restored creation in the Age to Come and another that seems clearly to promise universal salvation. The question, for those who assume that the New Testament must be uniform in theology (and I confess I am not of their number), is which of these two kinds of language can better explain the other? The former, after all, if the destruction of the reprobate is understood simply as total annihilation, would seem to reduce the latter to vacuous hyperbole. The latter, however, can conceivably explain the former in terms of a harsh purification that destroys the sinful self, but only for the sake of the resurrection of the redeemed creature.

Anyway, while I do sometimes find the misreadings vexing (even if I fully appreciate how convenient they often are for the critics), and while I think this book speaks for itself more than adequately, I have nevertheless learned over the years that understanding is always a collaboration. Both sides have to do their parts. Even the clearest of texts has to be met at least half way by the good intentions of the reader, but even a reader’s purest intentions can be thwarted by a text that presumes premises with which he or she is unfamiliar. And I have discovered that the parts of this book’s argument for which some readers have proved especially unprepared are found in its first and fourth meditations. So, perhaps it would be prudent to provide a brief guide to each here, for those whom it might assist.

In the case of Meditation One, for instance, which concerns the classical metaphysics of creatio ex nihilo and eschatology, I should probably point out that there are very old Christian teachings regarding the difference between the things that God positively wills and the things he merely permits, as well as between what God “antecedently” decrees in creating (his original purpose, that is) and what he “consequently” decrees in exercising his providence over a fallen world (his purpose as qualified in respect to sin). It is also a well-established principle of Christian thought, metaphysical and theological, that God is infinitely good and so can never directly or positively will evil. He may perhaps permit a natural evil (such as suffering or death) to occur, but only as providentially leading to a greater good; he cannot will it as an ultimate reality without thereby morally willing something evil. The purpose of this part of the book, however, and of the exercise in “game theory” it comprises, is to demonstrate that, considered in the full light of the doctrine of creation, and specifically from the vantage of eschatology, these distinctions between divine will and permission, or between antecedent and consequent divine decrees, or between natural and moral evil, fall apart. After all, it is only in the final form of creation in its fullness that what God intends in creating—and the complete calculus of what he is willing to “pay” to bring those intentions to fruition—will be known. At that final horizon, moreover, one cannot even really distinguish between “natural” and “moral” evils, at least not if any of those natural evils enter into the final, accomplished pattern of creation as God intends it. Even if God allows only for the mere possibility of an ultimately unredeemed natural evil in creation, this means that, in the very act of creation, he deemed this reality to be an acceptable price for the ends he desired and thereby, morally speaking, has willed it positively. In acting freely, all the possibilities to which the agent knowingly consents are things he or she has willed directly, as intrinsic conditions of the end to be achieved; one cannot positively will the whole without positively willing all the necessary parts of the whole (whether those parts exist in fully actual form or only as real possibilities). Hence, that final intentional horizon is of necessity a revelation not only of the nature of creation but of the nature of God. For any intentional act that is not conditional upon some prior necessity is a revelation of the moral nature of the agent.

As for Meditation Four, its reasoning is in one sense less complicated, in part because it is wholly negative: the point is, simply enough, that the now popular “free will defense” of the idea of an eternal hell is based on a logical fiction. Really, the essential claim is little more than what Christ is reported as saying in John’s Gospel: that “everyone committing sin is a slave to sin” (8:34), but that if you “know the truth...the truth will make you free” (8:32). The difficulty for many readers is that this part of the book’s argument relies upon a classical understanding of rational freedom—one that the common inheritance of both pagan antiquity and Christian tradition—that at one time was more or less universally presumed, and that still has no plausible alternative, but that modern persons rarely encounter. Most of us today presume the simple, late modern “libertarian” model of freedom, according to which the will is free to the degree that it can spontaneously posit purposes for itself, unconstrained by anything prior to that pure act of volition. But that model is nonsensical. Rational freedom (which is to say, the kind of freedom possessed by reasoning beings, which involves intention, deliberation, and judgment) is of its nature a reflective movement of the will, determined by what the intellect perceives as desirable in light of a more original, more general set of “transcendental” longings (that is, a constant, at times almost unconscious appetite for, say, goodness, or truth, or beauty). And to be perfectly free would be to possess the ability to know with absolute clarity, undistorted by ignorance or emotional trauma, what ends would really satisfy one’s truest and deepest desires, and to enjoy an unhindered ability to realize one’s nature by choosing those ends. Of course, in this life none of us has perfect freedom. But, to whatever degree we are free, it is because we can form judgments and make choices; and, conversely, to the degree that we lack rational competency—that we are deprived of full understanding and sanity—we are not free.

What, after all, makes any choice a free act? Principally, an end, a telos, toward which it is oriented. To act freely, that is, one must be able to conceive a purpose or object and then elect either to pursue or not to pursue it. If it were not for this purposiveness—this “final causality,” to use the classical term—the will’s operation would be nothing but a brute event, wholly determined by its physical antecedents, and therefore “free” only in the trivial sense of “random,” like an earthquake or a purely neural impulse. To be free, one must be able to choose this rather than that according to a real sense of which better satisfies one’s natural longing for, say, happiness or goodness or truth or beauty. One must have some rational index of ultimate ends that are desirable in and of themselves in order to judge lesser, more immediate ends. Hence there can be no real “empirical” freedom except as embraced within a prior determination of the rational will towards these “transcendentals.” There must be a “why” in any free choice, a sufficient reason for making it, a general longing that makes each specific choice possible, as leading toward some kind of happiness. You prove this every time you choose a salad at lunch rather than a plate of broken glass. I desire a particular work of art, say, because I have a deeper and more original longing for beauty, which that particular artwork can partially satisfy; and this ultimate horizon of desire for beauty gives me an index for that evaluation, judgment, and choice. We need not even posit that these transcendentals have some sort of real existence to affirm this (though, of course, Christians are obliged to believe in the reality of Truth and Goodness and so forth). We need only recognize that such an orientation is the necessary structure of thinking and willing, and that every finite employment of the will, to the degree that it is free, depends upon this deferral of rationales toward ends beyond the empirical. Otherwise, the physicalists would be right: what we take as free will would actually be nothing but a delusion generated by what is, in reality, a sequence of purely physical consequences generated by purely physical antecedents.

My argument in these pages, therefore, is not that we cannot reject God, but only that we cannot do so with perfect freedom. The power of choice in itself is not true freedom of the will. In a sense, a lunatic has a far larger range of real options than does a sane person, but only because he or she also has far less freedom. The lunatic might choose to run into a burning building on impulse, to see what it will feel like to die in flames; a sane man, because he can form a rational judgment of what can and cannot satisfy his nature, lacks so expansive a “liberty.”

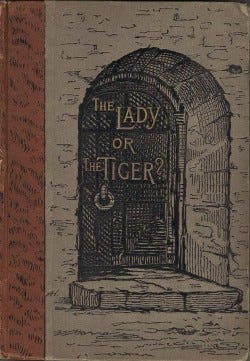

Consider, for instance, the classic story “The Lady, or the Tiger?” by the American author Frank R. Stockton. A handsome young courtier who has had the effrontery to conduct a romance with his king’s daughter is sentenced to the arena, where he must open one of two doors (as he chooses). Behind one waits a fierce and famished tiger, ready to devour him; behind the other, a beautiful maiden, ready to become his wife. These are the only two fates permitted him. And he does not know which door is which. The princess, however, who is watching from the gallery, has discovered which door leads to which fate, and discreetly signals to him to open the one on the right. The question the story leaves hanging is whether she has yielded to jealousy and directed her lover to his death, or whether she has yielded to her love for him and sent him to the arms of another woman. But we can simplify the tale. Let us say instead that the young courtier has a choice between a door behind which that tiger is still crouching and another behind which the girl of his dreams (say, the princess herself) is waiting. First of all, which door should he want to open? If he is perfectly sane and healthy, and barring other contingencies, the latter, obviously. We can agree, I hope, that one of the conditions that allows him to make a truly free decision in these circumstances is that he is not captive to some sort of dementia that would render him incapable of judging whether it would be better to be torn to shreds by a wild beast or to be happily wedded to the woman he loves. But that also means that his freedom—his liberty from delusion, that is—has already reduced the range of his possible preferences to only one of the two outcomes. Then, however, a more crucial question must be asked. Under which conditions can he better make a truly free choice: either knowing or not knowing which door is which? Obviously, the former. Otherwise, it is all a matter of chance, and his choice is an arbitrary decision forced on him by circumstance. The more he knows, therefore, the freer he becomes; but then, at the same time, the freer he is, the less there is to choose, and the more inevitable the choice he will make. In fact, what follows is not really a “choice” at all, precisely because it is a purely free movement of thought and will toward the end he most truly desires. He has been liberated from the need to choose arbitrarily, and so has been determined toward an inevitable terminus by his own freedom.

What then of the claim that hell could be the ultimate free choice of a rational spiritual nature? It is meaningless. To the very degree that a rational creature might reject the one transcendent reality that can alone satisfy its deepest needs and desires, that creature is in bondage. An injured, damaged, and deluded person might behave in such a manner, but never a free person. Freely, sanely, deliberatively to elect misery forever rather than bliss would be a form of madness. To call that madness freedom, in order to soothe our consciences and to continue to reconcile ourselves to a picture of reality that is morally absurd, is to talk gibberish. And, too, there is a deeper metaphysical logic here to be considered. It turns out, on any careful consideration of the matter, that only God himself—the infinite and transcendent Being, Goodness, Truth, and Beauty that is the source and end of all reality—could be the true necessary “final cause” for any really free rational creature. So no perfectly free will can choose any ultimate end other than God, and to the degree that a rational nature attempts to reject God it is simply deluded. In fact, an attempt at final rejection is the most that any such nature could ever accomplish, since a spirit’s ever deeper and more primordial longing for God is the whole substance of its rational volition. God—unlike a creature—could never appear to a spiritual nature as merely one option among others, which could be rejected without intentional remainder. God himself is the ceaseless transcendent orientation of the mind and will, in respect of which alone any merely finite object can be rejected, and so even in trying to reject God one would still be animated by a still deeper longing for God. So, just as God cannot positively will evil precisely because he is infinitely free, neither can we will evil in an ultimate sense, inasmuch as his infinite liberty is the source and end of our liberty too. Simply said, only in him are we truly free.

Ah, yes. A typo that no one noticed.

The tale of your friends' son hit close to home. I, too, am on the spectrum and had a similar experience when I was a young boy of nine. I remember lying in bed for many nights, crying for the injustice of it all. And from fear, too. "Am I going to Hell?" I thought. "Is being sad and afraid enough to condemn me to Hell, too?" These thoughts plagued me. My mother had to come sleep with me because I had become so inconsolable. As we lied together in bed, she would hug me and pet my hair, trying to calm me down. Finally, I calmed down but only after she told me that God couldn't possibly send anyone to Hell. Not even the most depraved psychopath. Still, it damaged my faith and it took fifteen years for me to return to the Christian faith.