[The following has been published before, under the title “Brilliant Bad Books,” but only in much shorter form. It was one of those pieces that I was forced to abbreviate for reasons of space when it first appeared, and it remained in that curtailed form when it appeared in one of my collections of essays. So here for the first time is my full tribute to the glorious Amanda McKittrick Ros. It seems to me a fitting sequel to my articles on writing. And I thought it might make a nice gift at the midway point of the twelve days of the feast. Blessings to all.]

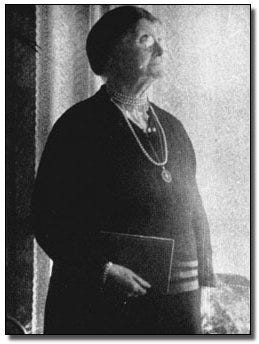

Best to begin in medias res, says Horace, so let me start with two exemplary excerpts from the works of the inimitable Irish writer Amanda McKittrick Ros (1860-1939). The first is the opening paragraph of the fourth chapter of her debut novel of 1897, Irene Iddesleigh:

When on the eve of glory, whilst brooding over the prospects of a bright and happy future, whilst meditating upon the risky right of justice, there we remain, wanderers on the cloudy surface of mental woe, disappointment and danger, inhabitants of the grim sphere of anticipated imagery, partakers of the poisonous dregs of concocted injustice. Yet such is life.

And the second is the opening sentence of 1898’s Delina Delaney:

Have you ever visited that portion of Erin’s plot that offers its sympathetic soil for the minute survey and scrutinous examination of those in political power, whose decision has wisely been the means before now of converting the stern and prejudiced, and reaching the hand of slight aid to share its strength in augmenting its agricultural richness?

I could not hope to put matters better than that. Neither could you. Neither could anyone else.

There has never been another literary figure remotely comparable to “the divine Amanda” (whose real name was Anna Margaret Ross, née McKittrick). She was, many discriminating readers believe, at once the single most atrocious writer who ever lived and also one of the most mesmerizingly delightful. She was supremely talentless—she was wholly incapable of producing a single intelligent or well-formed sentence—and yet her incompetence was so sui generis that it constituted a kind of genius.

Most bad writers, after all, tend to be bad in only the most boringly conventional ways; the ineptitudes of an Ayn Rand or Danielle Steel or Dan Brown are drearily predictable, and whatever malicious pleasure one can extract from them soon turns into a depressing surfeit. But the joy of reading Amanda McKittrick Ros is all but inexhaustible, because every line she wrote was utterly unprecedented in its sheer ghastliness. In the realm of bad literature, she was a pioneer of the spirit, tirelessly exploring new frontiers: a true innovator, prodigious and unique. No mere hack could have perfected a style of such horrendous and delirious originality. Once more, from Irene Iddesleigh:

“Speak! Irene! Wife! Woman! Do not sit in silence and allow the blood that now boils in my veins to ooze through cavities of unrestrained passion and trickle down to drench me with its crimson hue!”

One could labor for years on end to imitate that voice and never come close to pulling it off. To her admirers (and I am among the most fervent), her books are as inspired in their way as any great works of art could ever be. And those who have once fallen under her spell—Lord Beveridge, Mark Twain, Aldous Huxley, C.S. Lewis, Osbert Sitwell, J.R.R. Tolkien, Anthony Powell, E.V. Lucas, Siegfried Sassoon, D.B. Wyndham Lewis, to name a few—are her captives ever thereafter.

It was all quite unintentional, I hasten to add. She was not some brilliant parodist or cunning absurdist. She was, in fact, almost insanely devoid of anything like a sense of humor. Her visiting card in her later years was a perfect expression of her vision of herself: “Amanda McKittrick Ros, Authoress, At Home always to the honourable.” She took herself and her art with the utmost seriousness, and regarded all of those “critic crabs”—all those “evil-minded snapshots of spleen,” “bastard donkey-headed mites,” “poisonous apes,” “hogwashing hooligans,” “talent wipers of wormy order,” and “auctioneering agents of Satan”—who failed to recognize her genius as enemies and fiends, intent upon punishing her for having drawn back the veil from before the depravities of the ruling classes and having thereby perturbed “the bowels of millions.” One could say, I suppose, that she was a brilliant surrealist; but she was so only by inadvertence.

*******

“Amanda” came from the town of Ballynahinch in County Down originally. Her father was a schoolteacher and so she became one as well, and was teaching in a school at Larne in County Lantrim when she met and married Andrew Ross, a railway stationmaster. It was this poor soul who was obliged, on the occasion of the couple’s tenth anniversary in 1897, to pay a printer in Belfast to publish Irene Iddesleigh; his wife would accept no other present. She had begun writing the book two years earlier—if, before then, she had had any literary ambitions, she had kept them to herself—and was convinced that it was a masterpiece. She repaid him by amputating the second “s” of their surname for her published works in order to suggest some sort of connection to the Ros family, who ranked high among the local landed gentry.

The world had never before seen such a book. From its opening paragraphs, it announced itself as a kind of stella nova blazing in the firmament of English letters:

Sympathise with me, indeed! Ah, no! Cast your sympathy on the chill waves of troubled waters; fling it on the oases of futurity; dash it against the rock of gossip; or, better still, allow it to remain within the false and faithless bosom of buried scorn.

Such were a few remarks of Irene as she paced the beach of limited freedom, alone and unprotected. Sympathy can wound the breast of trodden patience,—it hath no rival to insure the feelings we possess, save that of sorrow.

And everything that followed sang the same uncanny music:

He was tempted to invest in the polluted stocks of magnified extension, and when their banks seemed swollen with rotten gear, gathered too often from the winds of wilful wrong, how the misty dust blinded his sight and drove him through the field of fashion and feeble effeminacy, which he once never meant to tread, landing him on the slippery rock of smutty touch, to wander into the hidden cavities of ancient fame, there to remain a blinded son of injustice and unparalleled wrong!

With this novel, all at once, the Amanda McKittrick Ros style had been established, in all its wild eccentricity: the obsessive fondness for alliteration, the spasmodically coiling and uncoiling sentences that never seem to arrive at any discernible meaning, the weirdly jarring turns of phrase, the riot of clashing metaphors, the convulsively lurching narratives, the long descriptive passages that seem to correspond to nothing in the physical world, the lunatic perorations in that nightmarish travesty of English, the galloping melodramatic plots that veer off again and again along bizarrely Gothic lanes… Bad marriages to wicked men, thwarted love, jealousy, sadism, suicide… More alliteration…

Practically no one would have noticed, however—the utter magnificence of the thing would have gone more or less unremarked—had the humorist Barry Pain not been sent a copy of the novel by a friend. He was so enchanted by what he read that he promptly wrote a satirical review for Black & White in which he declared Irene Iddesleigh “the book of the century.” Amanda was wounded by the review, and attacked its author in the preface of Delina Delaney as a “clay crab of corruption” and a “cancerous irritant wart”; but Pain’s article had turned her into a celebrity. Among the literati of London, it was even fashionable for a time to throw Amanda McKittrick Ros parties, where all the guests were required to talk like the characters from the novel (not that anyone could) and to take turns reading aloud from the text.

For the most part, mercifully enough, Amanda was unaware of the sheer scale and robust callousness of the mockery her book had provoked. She was, in any event, a sublimely arrogant and self-regarding woman, and was quite incapable of interpreting adverse comments on her work as anything other than expressions of spite and envy. So she pressed on. Delina Delaney—also privately published at the expense of her longsuffering and haplessly indulgent husband—was a longer and more ambitious work than its predecessor, and its tale of (once again) thwarted love, mad jealousy, intrigue, and murder was so elaborately convoluted and so arbitrary that it defies summary.

It also contains some of the most splendid specimens of her prose. Here is Amanda’s description of Delina’s occupation (needlework, in case it is not immediately clear):

She tried hard to keep herself a stranger to her poor old father's slight income by the use of the finest production of steel, whose blunt edge eyed the reely covering with marked greed, and offered its sharp dart to faultless fabrics of flaxen fineness.

Here too is the wicked Madam-de-Maine, sitting alone in her bedroom soon after shooting to death the poor old servant who had known that it was she who had poisoned Lord Gifford’s pudding:

Her frame sometimes shook to chorus a thirsty sob, as if she were again contemplating a similar ordeal. Eventually, however, the signs of nervousness, that now visited her, died and withered away, and a miraculous peace, sometimes seen on the marbled faces of Roman statuary, that exhibit strongly the polished calm of revengeful rulers, rested on her features.

And here is the moment when Delina and Lord Gifford first meet and all at once their love springs into luxuriant life:

Could a king, a prince, a duke—nay, even one of those ubiquitous invisibles who, we are led to believe, accompanies us when thinking, speaking, or acting—could even this sinless atom refrain from tainting its spotless gear with the wish of a human heart, as those grey eyes looked in bashful tenderness into the glittering jet revolvers that reflected their sparkling lustre from nave to circumference, casting a deepened brightness over the whole features of an innocent girl, and expressing, in invisible silence, the thoughts, nay, even the wish, of a fleshy triangle whose base had been bitten by order of the Bodiless Thinker.

Magnificent. Incomparable. Brava!

Sadly, it was the last of her novels to appear while she was alive. She did, however, produce two volumes of verse: Poems of Puncture in 1912 and Fumes of Formation in 1933. And she printed a few broadsheets for the troops during the Great War, one of which featured her poem “A Little Belgian Orphan,” a tale of German atrocities that begins with the extraordinary line “Daddy was a Belgian and so was Mammy too” and that includes such plangent couplets as

Just then they raised the little lad and threw him on the fire, And wreathed in smiles they watched him burn until he did expire

*******

Andrew Ross died in 1917, leaving Amanda to fend for herself, which her general impracticality made her unable to do particularly well. So she contracted a second marriage, to a prosperous farmer from County Down named Thomas Rodgers, which allowed her to dedicate herself wholly to her art. In 1926, moreover, she enjoyed a revival of interest in her works, when the Nonesuch Press published a new and particularly handsome edition of Irene Iddesleigh. Amanda, still not quite cognizant of the reasons for her enduring appeal, contentedly observed that her novel had now “risen to the shelf of classic.”

It may have been this that encouraged her to write her third and final novel, Helen Huddleson, which was still unfinished at the time of her death, but which appeared at last in 1969, with a final chapter supplied by her biographer Jack Loudan. It is a glorious performance. All of Amanda’s oddities are present in abundance, but now accompanied by a wonderful array of new perversities. Most striking of all is her wholly inexplicable decision to give most of the novel’s characters the names of fruits. In addition to the malevolent Lord Raspberry, there is Cherry, Duchess of Greengage, Sir Peter Plum, Mrs Strawberry, Madame Pear, the Earl of Grape, and Sir Christopher Currant—though, for variety’s sake, she tosses in a legume too, in the person of the housemaid Lily Lentil. Madame Pear is the chief villainess, and her dastardly retinue comprises

a swell staff of sweet-faced helpers swathed in stratagem, whose members and garments glowed with the lust of the loose, sparkled with the tears of the tortured, shone with the sunlight of bribery, dangled with the diamonds of distrust, slashed with sapphires of scandals.

By this point, Amanda had clearly perfected her personal style. Indeed, she had achieved entirely new amplitudes of inspiration:

They reached Canada after a very pleasant trip across the useful pond that stimulates the backbone of commerce more than any other known element since Noah, captain of the flood, kicked the bucket.

She had even elevated her alliteration to heights more dizzying than any she had hitherto conquered:

Ah dear Helen, I feel heart sick of this frivolous frittery fraternity of fragiles flitting round and about Earth’s huge plane wearing their mourning livery of religion as a cloud of design tainted with the milk of mockery.

I shall resist the temptation to quote any more of my favorite passages, however. I shall only remark that, to my mind, Helen is her supreme accomplishment.

*******

There is no moral to this tale. I have no better reason for talking about Amanda than the whim of the moment. At times, I confess, I feel a little guilty about my fondness for her books; there has always been a hint of cruelty in the devotion she excites in her admirers. My only defense is that I have come to feel a very genuine affection for her over the years, and am profoundly grateful for the sheer delight she has afforded me again and again since I first discovered her writings. There really was something madly brilliant about her books, and I sincerely treasure them. What other posterity should a writer crave?

So, rather than reproach myself, I shall simply remind myself that, as Amanda wrote,

Life is too often stripped of its pleasantness by the steps of false assumption, marring the true path of life-long happiness, which should be pebbled with principle, piety, purity and peace.

Again, I could not possibly put the matter better than that.

I especially treasure "bastard donkey-headed mites" as an epithet because it seems to imply the existence of legitimate donkey-headed mites got 'tween the lawful sheets.

To my eternal shame I had never heard of Mrs. Ros until Dr. Hart kindly shared with us this crowning achievement of the Western literature. I think we have finally discovered the true inspiration for Vogon poetry.