(The following is an essay of mine that first appeared on 27 July 2009, in a journal whose name seems now to elude me; it is also found in my collection A Splendid Wickedness and other essays. I reprint it here so that I need not recapitulate its contents in my final article in this series.)

My son was still too deeply immersed in his thousandth or so rereading of The Wind in the Willows to take an immediate interest in the copy of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince that I had just rescued for him from the chilly hinterlands of my library, so I decided to read it again myself. Memory, I found, had not really altered the story in my mind, but also had not quite prepared me for its total effect. I am no less susceptible to the tale’s charm than most of its readers are, I can honestly say, or to its fetching dreamlike atmosphere; but I still came away from the experience thinking that there is something rather mystifying about the perennial appeal of this book.

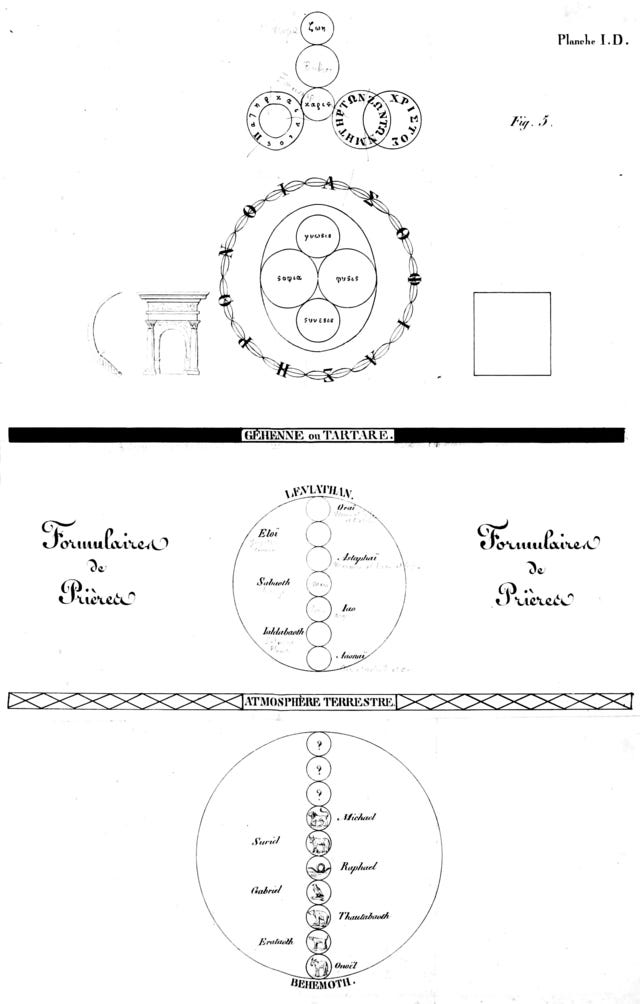

It is, for one thing, a deeply melancholy little fable, and while this is hardly a surprising quality in a book written by so incurably wistful an author—or at so dreadfully dark a moment in the world’s history (1943)—it is certainly a surprising quality in a children’s book of such enduring popularity. Children, as we all know, are quite capable of enjoying grim or frightening or perverse stories, and do not mind being a bit disturbed by what they read; but one generally does not expect them to have much of an appetite for tales that are morose, or pervaded by adult nostalgia, or freighted with spiritual disenchantments. The Little Prince is all of these. It is, moreover, a somewhat dated piece, what with its crowded gallery of slightly annoying symbolist personifications—the proud rose, the fox who wants to be tamed, the serpent who brings eternal sleep—all of which probably seemed exquisitely profound to a rather romantic French writer reared in the long lavender shadow of Maurice Maeterlinck, but all of which now, on too pitilessly close an inspection, possess little more than a quaint pasteboard bathos. (Though, to make a clean breast of things, I actually like all those bits.) My error may, of course, lie in assuming that it is in fact children, rather than their parents, who are the principal admirers of the work. I honestly do not recall what my reaction to it was when I was, say, seven; but I know that what fascinates me about it now is the enigmatic but fairly obvious Christian Gnostic allegory at its heart. The Little Prince is—if not a savior figure—nonetheless a bearer of a higher wisdom, blessed with a positively transcendent innocence, too pure for our fallen reality and so no more than a temporary sojourner here on earth. He comes to us out of an eternal childhood and, for that very reason, has never been rendered foolish by experience. His own world contains both good and evil seeds, we are told, but he is without fault. He even, in descending into our world, passes through the planetary spheres, pausing briefly at each to converse with its reigning archon: the king who imagines himself ruler of all things, the vain man who demands only adoration, the drunkard sunk in shame, the heartlessly calculating man of business, the harried and miserable lamplighter, the explorer who never leaves his study—all quite absurdly self-important and all trapped within their fated roles.

Then, to one lone, eccentric, and somewhat unworldly man, stranded in the desert, he brings enlightenment, and that of a rather thin and impalpable variety: the knowledge that somewhere above this world a divine child is laughing and the ability therefore to hear (as others cannot) the laughter of the stars. Then the Little Prince departs again, even more mysteriously than he came; unable to ascend again to his true home while still burdened by an earthly body, he must submit to the serpent’s bite; and the next day even his body has vanished.

Perhaps this is precisely what the book’s admirers really like about it—or, at least, what most of the adults and a few particularly lugubrious children like about it. After all, its sadness is a sadness that emanates from the inescapable dilemma of the modern spiritual imagination. In a sense, a certain “Gnostic turn” is inevitable for us today when we attempt to find our way towards the transcendent, inasmuch as we begin all our spiritual journeys now in a world from which the transcendent has been forcibly expelled, and not as a result of mere cultural prejudice.

The world we inhabit—the world our imaginations know and within which our deepest desires must move—is the world after Darwin (and Marx and Freud and a host of other prophets of disenchantment, but first and foremost Darwin); we simply cannot now (if we are paying attention) imagine a universe whose grandeurs and mysteries unambiguously lead the reflective mind beyond themselves towards a transcendent order both benign and provident. There was a time, perhaps, when nature really did seem to speak with considerable eloquence of a good creator and a rational creation. Formal and final causes were everywhere visible, guiding material and efficient causes towards their several—yet harmoniously interwoven—ends. The endless diversity of nature was an elaborate, gorgeous, and glittering hierarchy, rising from the dust to heights beyond the merely cosmic, comprising worms and angels within a single continuum of articulate splendor. That was a while ago, however.

Whether or not Darwinism is really quite the “universal solvent” that Daniel Dennett and others believe it is, and whether or not, logically considered, it really does away entirely with the need for some concept of final or formal causes, at the level of general cultural imagination it has certainly drawn a veil for us between experience of the world and knowledge of God. Nature as many of us cannot help but see it now, no matter how much we may delight in its intricacies and beauties and dangers, is primarily an immense and mindless machine that generates poignantly ephemeral life out of a perpetual chaos of violence and death. And, far from constituting a rational continuum, obedient to what Arthur Lovejoy liked to call the principium plenitudinis (that is, the metaphysical law that no possible level of existence can be absent within a complete cosmic order), nature’s diversity appears to us now as only the fortuitous result of a combination of spontaneous material forces and enormous spans of time. Whereas, for example, an ape’s morphological proximity to a man could once have appeared to educated minds as evidence of a perfect arrangement of graded eidetic kinds within an ideal universe, that same similarity appears to us now to be chiefly the residue of a random series of divergences and ramifications and attritions within a phylogenic series, guided only by chance and material necessity. A likeness within difference that at one time could be seen as the line of demarcation between angelic intellect and bestial impulse is now the humbling reminder of an arbitrary division of fortunes within a single mammalian family; the ape does not just point upwards towards us; he also draws us down again into the mire of animal organism.

Now, this is not to say that many of us cannot feel quite at peace with this state of affairs. I, for one, rejoice in the knowledge of my kinship with the gentle and venerable mountain gorilla, and suspect that—of the two of us—I may be the more honored by the association. Moreover, I do not really believe that an acknowledgment of the fact of special evolution obliges me to abandon the instinctive Platonism of my nature that tells me that goodness, truth, and beauty still infuse all of creation with a transcendent purpose, one that includes both me and my distant simian cousin. But even I, reflecting on the vast torment and ruin of nature, cannot help at times slipping into a slightly Manichaean mood and wondering whether he and I are not both together involved in some great tragic cosmic drama in which good and evil, light and darkness, even spirit and matter ceaselessly vie with one another. At such moments, when looking for a source of spiritual comfort, my eyes do tend to turn somewhat upward and away from the world.

Hans Jonas defined the special pathos of Gnosticism as the unearthly allure of the call from beyond, the voice of the stranger God that resonates within the soul that knows itself to be only a resident alien in this world. And he saw this as a pathos peculiarly familiar to us in this the age of “unaccommodated man.” This is undoubtedly correct, but it should also be said that this “call of the stranger God” is itself only one modality of a more general summons audible to all persons (except those who have laboriously deafened themselves to it), more or less at all times. It is that same experience of wonder at the sheer unexpectedness and mystery of existence that Plato and Aristotle called the beginning of philosophy, or the same primordial agitation of desire that Augustine described as the unquiet heart’s yearning for God. The distinctive note that shifts this summons into a Gnostic register, however, is that of alienation from the world; and this is largely a matter of cultural circumstance.

It is undoubtedly the case that it is our shared imaginative grammar that determines for us how and to what degree we can reconcile our native human longing for the divine with our love of the things of earth. In a more hospitable cosmos than ours now appears to be, it was much easier to be at home in the world and to believe that that which lies farthest beyond us is also that which lies most deeply within all things; in such a cosmos, transcendence is the mystery at once of the far and the near. But the modern perspective seems to shatter that unity; for us, to a greater degree than for most of our more distant ancestors, the beyond is only beyond, and transcendence is a kind of absence or impenetrable paradox, announced to us not so much in the splendor and order of nature as in our alienation from it.

This is why so much of the art of the modern age, high and low, so often treats of spiritual longing in Gnostic terms. French literature—being at once the richest and most diseased of any nation—provides the most vivid examples, produced by believers and unbelievers alike: Hugo, Huysmans, Anatole France, Mallarmé, Verlaine, Bernanos, and, of course, Baudelaire (whose inner sense of a certain “Gnostic paradox” generated a poetry at once fervently pious and blasphemously decadent). The novels of Patrick White (especially Riders in the Chariot) might be the most striking recent specimens of high Gnosticism in English letters. At a considerably more popular level, a great deal of science fiction, written or cinematic, turns again and again to Gnostic themes. A particularly famous example would be David Lindsay’s atrociously written, but oddly absorbing, A Voyage to Arcturus—to which one should subjoin a mention of Harold Bloom’s virtual reconstruction thereof, the even more hermetic The Flight to Lucifer. And of science fiction films constructed around Gnostic themes—implicit or explicit—there is already a notable tradition: George Lucas’s 1970 filmTHX 1138, for instance, or the Matrix trilogy. Two films written by Andrew Niccol—1997’s Gattaca and 1998’s The Truman Show—were both consciously Christian Gnostic fables; the latter especially was an affecting expression not only of a certain Gnostic paranoia regarding the nature of reality, but of faith in a spiritual dignity in the soul that transcends the world (it even ends with a rather splendid and moving confrontation between the hero, the one “true man” in the tale, and the demiurge of the universe from which he seeks escape).

My final observation, I suppose, would be this: Our longing for transcendence is inextinguishable in us, and the appeal of the transcendent to our deepest natures will always be audible and visible to us in some form—first and finally in the form of beauty—and will continue to waken in us both wonder and an often inexpressible unhappiness. But in an age such as ours, within the picture of the world that now prevails, that beauty must seem more ambiguous, more beleaguered, and the call of transcendence more elusive of interpretation, like a voice heard in a dream. In the absence of that scale of shining mediations that once seemed seamlessly to unite the immanent and the transcendent, the earthly and the heavenly, nature and supernature, we are nevertheless still open to the same summons issued in every age to every soul; but it must for now come to us as something more mysterious, tragic, and terrible than it once was.

This is very good stuff but I do wonder, the older I get, whether the sense of the ancient world finding evidences of kindly gods and inherent order in nature isn’t something of a projection we’ve inherited from Roman (and to a lesser extent Greek) antiquity and a reflection more of wistfulness for a lost era of shepherds and forest oracles than of the somewhat more chthonic, certainly less Apollonian image we more often get from much earlier survivals, or even the remains of Celtic, German, Slavic paganism, etc. Not to mention the practically miserabilist cosmology of the Sumerians, for whom a forest is a nightmare realm crawling with scorpions and a god is a parasitic being that swarms over sacrifices like a fly on a dropping. I wonder if, in the west at any rate, our sense of alienation from nature isn’t very ancient, I guess. And our sense of being alienated from a nature to which we were formerly close is also pretty old, much older than we sometimes assume. But I’m probably just being a donkey about this.

This is simply lovely. To appreciate what all of these modern stories are after, while not fully embracing it—and to be able to appreciate it properly, because one doesn’t fully embrace it—is so illuminating. Perhaps you will give us a few more sentences on Harold Bloom at some point, who was likewise engaged with the gnostic current in our culture, but wasn’t able (as far as I can tell) to distinguish it from Platonism, so that he lacked the distance from the current that would have enabled him to understand it, rather than being swallowed up in it. I wonder, though, whether the summons of transcendence “_must_ come to as us something more mysterious, tragic, and terrible than it once was”? Certainly it does often come to us in that way; this is totally clear. And yet we have Gerard Manley Hopkins, Walt Whitman, and Mary Oliver, for whom it seems far from mysterious, tragic, or terrible. Rather, it’s the most manifest and embracing feature of their experience. I’m not sure that the “scale of shining mediations” is entirely absent, for them or for us.