[This article originally appeared on 16 March 2010, in a journal whose name continues to elude me. I reprint it here as an accompaniment to my translation of “The Peach Blossom Spring,” which appeared a day or so ago. I have grudgingly altered my transliteration of Chinese names and words in accordance with current Pinyin usage.]

The Sanest of Men

We are now a few weeks into the Chinese New Year (a year of the Tiger, incidentally, elementally specified as metal, metaphysically specified as yang). We celebrated the inception of the current calendar, as we like to do, not because any of us is Chinese, but because some of us suffer from a certain pathetic Sinophilia (in my case expressed by, among other things, an unrequited passion for Chinese ideograms) and because we like having a resplendently colorful festival to observe during the latter part of winter.

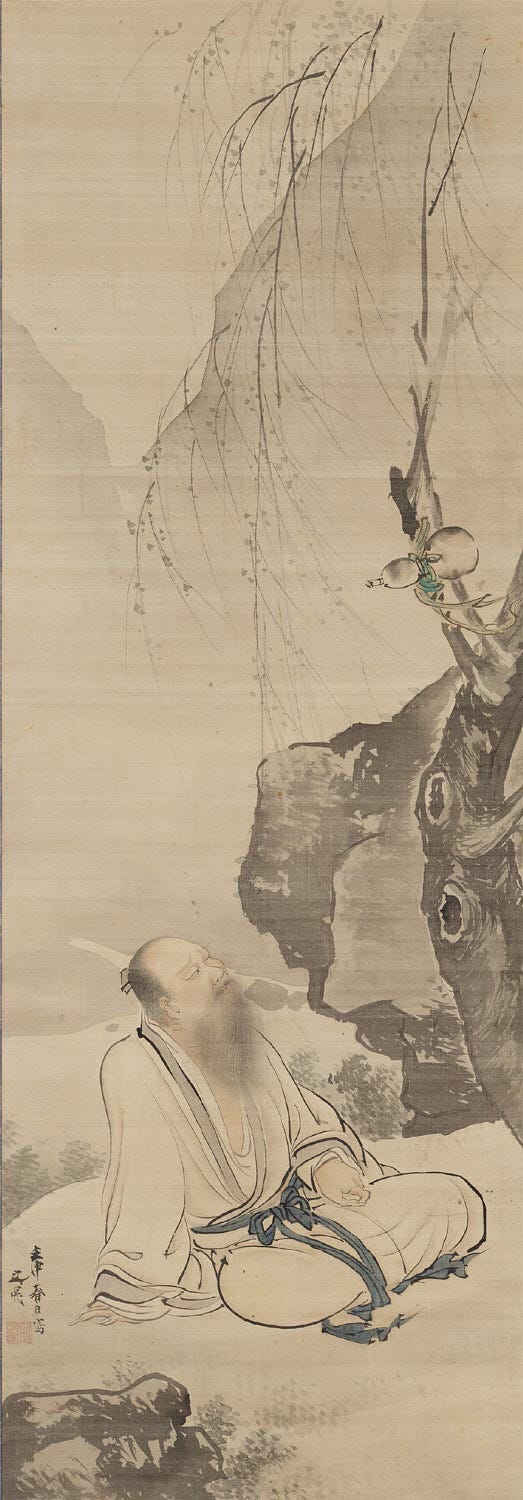

It seems an auspicious time, therefore, to pay tribute to one of my favorite figures from China’s long and glorious cultural history: the great poet Tao Yuanming (AD 365-427), also known as Tao Qian (or T’ao Ch’ien in the Wade-Giles transliteration). In China he is revered not only as one of the two fathers of the high tradition of Chinese poetry—the other being Xie Lingyun (AD 385-433)—but also as a great sage, one who has been claimed, at various times, by the Confucian, Daoist, and Chan (Zen) traditions (the last even though he was not a Buddhist). In fact, one popular—if utterly fanciful—tradition has it that Tao is one of the figures in the famous image of the Three Laughing Sages, although it is not entirely clear whether he should be considered the Confucian or the Daoist in the scene. And a Chinese Buddhist scholar I know has gone so far as to say that, in his opinion, Tao is as important a figure in the formation of Chinese Buddhism as Bodhidharma (the Indian missionary regarded as the first patriarch in the East Asian tradition), and perhaps more important as far as the peculiar sensibility of Zen is concerned.

Tao was not a prolific writer; in fact, he left behind only a small collection of verse, a few short essays, and a single letter written to his son. And, in his own day, his poetry was not esteemed nearly as highly as it later would be. But the great efflorescence of Chinese poetic culture during the Tang and Sung Dynasties (from the eighth to the thirteenth centuries) was inspired, in large part, by a fascination with Tao and his work. In his poems, the great writers of China’s poetic golden age found a model worthy of endless emulation: poetry written in “the voice of nature,” with perfect virtuosity, exquisite in its almost magical combination of subtlety and simplicity, and at its most lyrical precisely where it appeared least adorned. It was the great Sung poet Su Shi (Su Dongpo) who provided the most famous formulation of that peculiar quality that made Tao’s verse so entrancing to his admirers and imitators: “On the outside,” Su said, “it is withered, but on the inside abundant. It appears plain, and yet is truly beautiful.” It would not be exaggeration to say that it was Tao, more than anyone else, who bequeathed to Chinese literature certain of its most pronounced aesthetic values: immediacy, limpidity, and a veneration of the natural order.

As estimable and impressive as all of this is, however, my own affection for Tao arises from my conviction that, if the stories about him are a fair representation of his character, he was simply one of the sanest human beings who ever lived. And, in fact, this has always been a prominent feature of his reputation and his appeal. It was not only his poetry, but his persona, that left an indelible impress on the Chinese spirit, and that all peoples might do well to regard as a sound model of almost perfect mental and emotional health.

I should be clear here. Sanity is not sanctity (indeed, the latter is often achieved only by the forfeit of the former). Tao was neither a saint nor a mystic; he was a profoundly wise man, but he was not a purveyor of any “spiritual wisdom”. In fact, he scrupulously avoided taking the only path of spiritual liberation open to him in his day. Huiyuan, the abbot of the great Buddhist monastery of Lu Mountain, was so anxious to conscript Tao into the local society of Buddhists that he even—contrary to all proper discipline—allowed his monastery to serve wine when Tao was visiting. But, though Tao happily emptied the cup (wine being possibly his greatest passion), he still declined to embrace the dharma. He was temperamentally averse to asceticism, he detested inflexible regimens, and—while his relations with the Buddhists were cordial and kindly—he valued the joys of family and household far above the prospect of a salvation so laboriously won.

So, when I speak of Tao’s sanity, I mean only that he lived as a man who is entirely at home in the ordinary world ought to live. And I say this because I take it as an irrefragable maxim that the essence of mental and spiritual health is to care deeply about a very few, particularly precious, and intimately familiar things, and to regard much of the rest of human affairs with generous indifference; and I take it also that health of this sort is attainable only to the degree that one is free of ambition. Of course, if everyone were wholly sane, in this sense, nothing would ever get done—which would, I suppose, be a bad thing. For instance, as the world goes now, we seem to have some need for politicians; and, while modern democracy is a system that insures that power will almost invariably be given to those persons who are least morally qualified to wield it, it is just barely imaginable that a largely virtuous political class could be cultivated under more propitious circumstances. But, whether virtuous or vicious, only a person who is somewhat deranged could ever possibly care enough about politics to want to participate in its processes; anyone able to read a piece of legislation with interest is already a tad demented, and anyone willing to write a piece of legislation clearly suffers from a minor obsessive psychosis. God bless them all, but may God also spare us their dark fate.

Tao was the exact opposite of such a person. He was entirely incapable of political interests, and entirely devoid of whatever spiritual malady or degeneracy it is that makes certain men and women harbor an ambition for political office. He assumed the cognomen Qian—“Recluse”—in middle age precisely to give notice to the world that he had no intention of ever resuming any of the official responsibilities or titles that had occasionally been thrust upon him as a young man, in part by the accidents of his birth, but in larger part by the exigencies of poverty. He came from a particularly distinguished and accomplished line of classically educated Confucian scholars, of the sort who were trained and expected to serve as the administrators and magistrates of the Middle Kingdom’s government; but he preferred farming. His family, however, was not wealthy, and for many years he could not make his farm solvent.

At the age of twenty-nine, he took up a post in his local provincial government (near Xinyang); but he soon found that he could not play the role of deferential subordinate to a gaggle of pompous bureaucrats and returned to his farm. Financial necessity forced him again into public service from 395 to 400 (a period of considerable civil strife), but in 401 he took leave of his duties and for three years succeeded in wringing his subsistence from the soil. In 405, however, after an injury had made the exertions of plowing, sowing, and reaping difficult for him, and after he had allegedly considered a career as a minstrel to pay for the upkeep of his garden, friends prevailed on him to enter the service of the imperial general (and usurper) Liu Yu; later, he served under the general (and usurper) Liu Jingxuan; finally, he was convinced to accept the position of government magistrate in Penze.

His tenure of only eighty days in this, his final government appointment is the stuff of legend. Soon after taking up his seal of office, he dictated that all the government fields in his jurisdiction were to be planted exclusively with the sort of glutinous rice used for making wine. His wife prevailed upon him to make slightly more prudent use of public resources, but even then he consented to allowing only a sixth of the fields to be sowed with mere comestible rice instead. Otherwise he discharged his responsibilities with as much vigor as he could muster (which was not much, as it happens), and never with more than was required. He could never, however, make his nature obedient to the protocols of office. On being told by his assistant one day that he should fasten up his girdle in order to pay his respects to a visiting government inspector, Tao simply groaned and remarked that he had no intention of bowing and scraping to some oaf just in order to earn a few bushels of rice. That same day, he resigned his office and returned to his farm for good.

Thereafter, for more than twenty years, he politely refused every entreaty to return to public life, and devoted himself only to those things he loved: his farm, his poetry (which, he said, he wrote only for his own amusement), the perennial cycles of the natural world, the transitory music of familial affection, and wine. Everything else he did his best to ignore. He consciously chose obscurity over preeminence, poverty over wealth and preferment, and family over society. He was, all the evidence suggests, almost boundlessly contented. It would be hard, in fact, to imagine a soul congenitally less tortured than his; the organism of his temperament was so sound that practically nothing could disrupt its equilibrium. He was not a sociable man, but in his time and place, among discerning persons, there was no one whose society was more eagerly sought. One of his friends even went so far as to lay “honeyed” traps for him by arranging for tables with flagons of wine on them to be set in his path when he was out walking; Tao generally could not be persuaded to stop anywhere for more than a few moments, but where there was wine he was always willing to sit down and talk for hours.

The principal virtue that Tao pursued and praised, and that he refined to utter perfection, was that of xian, which is usually translated as “idleness.” This should not, however, be confused with “laziness”; farming, after all, is hardly an occupation for the indolent. Rather, xian is a condition of deep peace, a kind of interior quietude. It is not exactly a state of detachment: for one thing, it is not the practice of determined spiritual austerity, as “detachment” often is; for another, and more importantly, xian ultimately flows from genuine attachment to the right things. It is a kind of inability to be agitated by trifles or distracted by irrational appetites, and a capacity for total contentment in doing nothing at all when nothing at all is what needs to be done.

Around this still center within himself, this abiding xian, Tao cultivated a nearly limitlessly appealing character: gentle without being mawkish or servile, humorous without any propensity for cruelty, proud without a trace of arrogance or pomposity, sensualist without taint of depravity or greed. He was a man who made room for his appetites (which were few), without being enslaved by them. For instance, he could certainly drink too much now and then, but for the most part he chose to drink only enough to bedizen the world with a certain amiable glow; and even this he did only on occasion. He was also a man, all the accounts concur, of deep and sympathetic kindness. His one surviving letter has a rather touching passage in which he enjoins his son to be kind to the peasant boy Tao has hired to help with the farming, “for he too is someone’s son.”

It is, needless to say, something of a pleasant irony that a man who craved rustic obscurity should have become one of the great pillars supporting the “gold and jade palace” of Chinese cultural identity. But, of course, it was Tao’s very want of worldly ambition that allowed him to bequeath what he did to later ages. He died largely impoverished, but left behind a joyful and inextirpable cultural memory, a particularly delightful pattern of the ideal man, and a small body of perfectly accomplished art; and he was able to do all this because—as I have said—he was so imperturbably and incorrigibly sane.

I should not go on, however. As I write, it is nearing evening, and a light snow is falling among the trees of the woods where I live; the upper slopes of the mountain that rises above my home are still white with the heavy snows of two weeks ago; I am listening just now to a particularly haunting piece of music (an “Ipirotikos” from the third book of Skalkottas’s 36 Greek Dances); the peculiar quality of the incipient twilight bathes everything in a faint and slightly uncanny silver blue. I cannot imagine Tao Qian would have allowed such a moment to pass unenjoyed while he wrote a long encomium to a dead poet. So I will simply ask that persons of good will, perhaps some time before the first lunar month of the current Year of the Tiger expires, raise a cup (rice wine, ideally, but tea would do) in tribute to a man most of us would do well, whenever possible, to emulate.

Beautiful piece. All I’ve got to add is this little gem by Wang Ji where Tao makes an appearance

Farmers

All his life Ruan Ji was lazy,

And Xi Kang was a carefree spirit.

When they met, they drank their fill,

Sat alone, wrote a few lines,

Tried raising cranes by a tiny pool,

Pastured piglets in tranquil fields.

Grass grew over Tao Yuanming's path,

Flowering trees hid Yang Xiong's cottage.

Lie on your bed, watch your wife weave,

Up a hill and urge your son to hoe-

Then turn your head and the quests for the immortals

Become all one great emptiness.

Are you much of a tea drinker David? One the great pleasures of my life is drinking good aged Sheng Pu-erh, Wuyi Oolong and some of the terpene heavy Taiwanese stuff. Gong fu of course.