[I have two reasons for republishing this particular essay, which first appeared in October 2009. The first is that I have been a little under the weather for the past several days, having contracted something somewhere from something or someone somehow, and so my next regular article may be a day or so late. The second is that I am considering a piece on fairy-tales to appear here at some point in the next few weeks, and so a reflection on fairy-lore might not be out of place. I should point out here, moreover, that John Milbank has long since repudiated his errors—vide infra—regarding the indigenous fairy-folk of the Americas, and is much the better man for having done so.]

As All Souls nears, spare a thought, if you will, and a little pity for the poor Rev. Robert Kirk, who lived from 1644 to 1692, and whose mortal remains rest—or do they?—in his parish kirkyard in Aberfoyle, a Scottish village lying near the Laggan River and at the foot of Craigmore. The great slab of his gravestone is in much the same condition as most of the other funerary markers that survive from the seventeenth century in those latitudes: smoothed and darkened by the winds and rains of three centuries, brindled with dark green and pale glaucous lichens, gently sunken to one side by a slight subsidence in the soil, and bearing an inscription (“Robertus Kirk, A.M./ Linguæ Hiberniæ Lumen”) now worn down to a shallow and barely legible intaglio of milky gray. Such is the sad impermanence even of stone. Perhaps it does not matter all that much, however; the marker may be only a cenotaph, when all is said and done. Local legend has it that there is nothing more interred beneath that slowly dissolving monument than a coffin filled with rocks, the good reverend’s body having been spirited away by fairies soon after his sepulture, to be kept till the end of time in their mansions beneath Doon Hill (the garbled Anglicization, I assume, of “dun sitheen” or “fairy knoll”), by which device they are able also to keep his soul imprisoned in the great pine that grows on the hill’s crest. Another, less terrible version of the same story says that Kirk is not so much a prisoner of the fairies as an ambassador, able to convey messages between two realms that over the years have become increasingly estranged from one another. Whatever the case, the great tree of Doon Hill is still called the Minister’s Pine, and to this day anyone who visits it will find bright strips of cloth—upon which wishes have been written—tied about it or draped from the branches of surrounding trees.

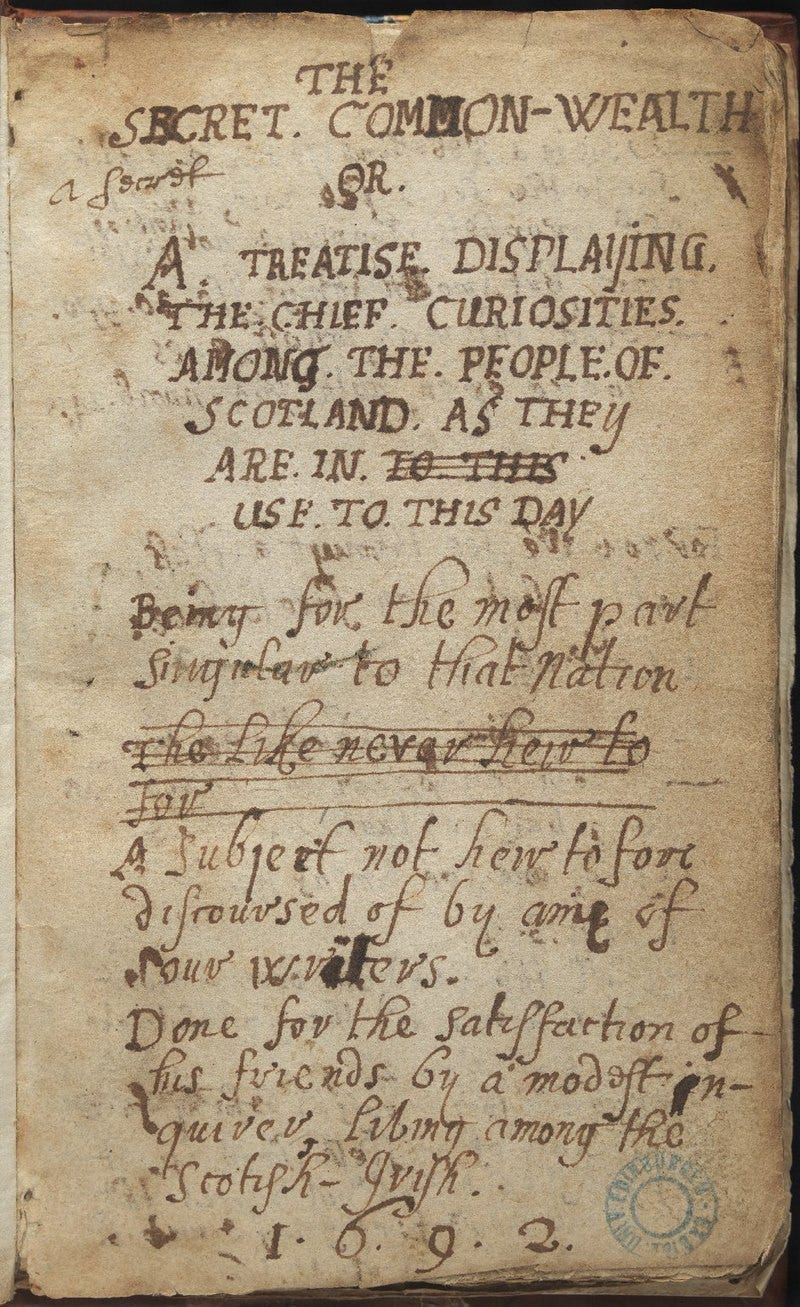

If the legend is true (and I, as any sane man ought, choose to believe it is), Rev. Kirk was the victim not only of the spite of a notoriously capricious folk, but of his own curiosity. A scholar trained at St. Andrew’s and Edinburgh, a master of Celtic tongues, the author of the Gaelic Psalter of 1684, a theologian and student of antique lore, Kirk’s greatest intellectual achievements were as a natural scientist (so to speak) of the hidden realm. He is best remembered for his treatise of 1691 The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns, and Fairies. There is some dispute regarding whether a published edition of this work was actually produced in Kirk’s time or whether instead Sir Walter Scott’s edition of 1815 was its first appearance in print; but the form in which it is best known now is in Andrew Lang’s critical edition of 1893 (which the always indispensable Dover Publications has recently made available again at a reasonable price). Whatever the case, it was not long after completing the book, which may have revealed more than was prudent, that Kirk met his end. He may have trespassed perhaps once too often upon the clandestine counsels of the Unseelie Court and so, on one of his frequent nighttime walks upon Doon Hill—which lay between his parish and his house, and which he was convinced was an entranceway into the other land—he simply fell into a swoon and died (or appeared to die).

Kirk’s true fate would have remained unknown, however, had he not, shortly after his obsequies, made a posthumous visit in a vision to his cousin, Graham of Duchray, in order to relate what had actually happened and to entreat his cousin to assist him in escaping his captors. At the time of Kirk’s death (or abduction), his wife had been with child and had since given birth to a son; Kirk promised that he—or his phantom, at any rate—would appear at the child’s baptism, and that at that time he could be released from his bondage and return to his family if his cousin would at that moment throw an iron knife at his apparition. Graham of Duchray came prepared on the day, but the actual sight of his cousin’s revenant—which did indeed appear—so froze him with wonder that he forgot to do as he had been bidden until it was too late. And so Kirk vanished again and his spirit remained imprisoned in the pine on Doon Hill.

Sad though Kirk’s fate was, we should remember that he was neither the first nor the last naturalist to fall a prey to the species he studied, and should at least be grateful that we still have the fruit of his researches to hand. The Hidden Commonwealth rewards frequent readings, even by persons so fanatical in their prejudices as to refuse to believe its reports (the sort of tragically deluded souls who mistake the book for a mere compendium of folklore). Kirk’s real concern, as it happens, was not simply the fairy realm, but also that rare breed of mortals who enjoy the ability to see its inhabitants with their own eyes. In large part, it is a treatise on the “second sight,” a special gift that Kirk believed to be possessed by only certain specially privileged souls—a great many of whom were, like Kirk himself, seventh sons—and one whose reality is attested not only in folklore, but also in scripture. Not to everyone do the “peaceable folk” appear, it seems, but a wealth of credible anecdotes—concerning persons who have experienced remarkable flashes of foreknowledge or encounters with the specters of friends who have died far away or other uncanny revelations—prove that there are those who have from birth been granted the ability to see the unseen, and even in many cases to pierce the veil within which the fairy realm is hidden. And such individuals, says Kirk, are of the same family as the prophets of ancient Israel, and of all the truly inspired prophets of every land and every race.

That said, one does learn quite a lot of elfin and mystical lore from Kirk too. He relates stories of the fairies’ cruel mischief, such as their wicked habit of carrying away new mothers to act as wet nurses to fairy infants, but also tells tales of their frequent benignity; he discourses on the moral character of the “subterranean people”, explains how each of us is attended through life by an ethereal double who sometimes lingers on in this world after we die, and provides any number of other fascinating facts about those dimensions of the world into which most of us cannot peer. And he dismisses altogether any notion that to believe such things is heathen superstition, and certainly any anxiety that these beings are actually demons. Fairies are, says Kirk, nothing but those elemental guardians of the nations who, according to scripture, have been appointed as wardens in the earth, but who frequently forget their roles and resist the sway of God. They are dangerous, but not evil; they are, rather, morally neutral, like the forces of material nature.

One aspect of Kirk’s investigations I find especially interesting is the purely autochthonous quality he ascribes to the second sight. Once removed from his or her native heath, says Kirk, a prophet loses the ability to see the other world, and becomes just as blind to preternatural presences as is any other mortal. A true seer draws his or her preternatural strength from his or her native heath, and when separated from it is like Antaeus raised up off the earth. Not only is every fairy a genius loci; every seer is a vates loci with a strictly limited charter. And the reason it pleases me to learn this is that it allows me to offer a riposte to an English friend of mine—a famous theologian whose name (which is John Milbank) I should probably withhold—who has quite a keen interest in fairies, and who regards it as a signal mark of the spiritual inferiority of America that its woods and dells, mountains and streams, are devoid of such entities. In proof of this, he once cited to me the report of some English traveler in the New World who sent back a dispatch from Newfoundland (or somewhere like that) complaining that there were no fairies to be found in those desolate climes. But, ah no, I can say (having read Kirk), of course some displaced Sassenach wandering in the woods of North America would be unable to perceive any of their sidhe inhabitants, since whatever faculty he might have possessed for catching sight of them would have deserted him when he left England. And, anyway, anyone familiar with the Native lore of the Americas knows that multitudes of dangerous and beneficent fay haunt or haunted these lands. They may sometimes—but only sometimes—lack a little of the winsome charm of their European counterparts, not having been exposed to centuries of Graeco-Roman and Christian civilization (or, for that matter, decadence); and on occasion they may therefore be somewhat more Titanic than Olympian in their general character and deportment; but they certainly do not merit disdain or a refusal to acknowledge their existence.

Anyway, be that as it may, I have a few observations to make regarding Kirk and regarding his way of seeing the world.

The first is that it is certainly the case that he undertook his researches into folklore out of a genuine interest in the traditions of the Celtic north, and also out of what appears to be a deep conviction that those traditions touch upon a real dimension of vital intelligence or intelligences residing in the world all about us, occasionally visible and audible to us, but for the most part outside the reach of our dull, earthbound senses. That said, there is good reason to believe that he wrote The Secret Commonwealth, and placed so strong an emphasis on scriptural attestations of the reality both of elemental spirits and of the second sight, also because he lived in the days of the early modern witch-hunting craze, when more than a few harmless Scottish country folk who innocently dabbled in the lore of the hidden world had found themselves arraigned by Presbyterian courts for practicing the black arts; it is very likely that Kirk was attempting to enter a brief in behalf of these unfortunate souls by providing a theological warrant for their beliefs. And, after all, such warrant really really can be found in the Bible if one chooses to look for it, and Kirk was simply a more careful reader than most other Christians on this matter. True, Christian tradition came early on in its development to abominate all the lesser spirits venerated or feared by pre-Christian culture as just so many demons prowling about the world with bad intentions, there is quite another view that might have been extracted from the New Testament, the Pauline corpus in particular; in certain of the epistles, these elemental powers seem to have the character not of malevolent demons but of somewhat mutinous deputies of God, part of the compromised cosmic hierarchy of powers and principalities whom Christ by his resurrection has subdued, but not necessarily condemned as servants of evil; Colossians 1:20 seems to speak of these powers as being not simply conquered by Christ, but actually reconciled with God in the process.

In any event, theological concerns aside, my final observation is that there was an essential sanity in Kirk’s approach to reality that we would all do well to emulate whenever we find ourselves gravitating toward the obscene fantasy of a purely mechanical natural order. One need not yet believe in fairies to grasp that there is no good reason why one ought not to do so, and that there may even be some moral imperative that one should. To see the world as inhabited by these vital intelligences, or to believe that behind the outward forms of nature there might be an unperceived realm of intelligent order, is simply to respond rationally to one of the ways in which the world seems to address us when we intuit simultaneously its rational frame and the depth of mystery it seems to hide from us. It may be the case, admittedly, that our understanding of that unseen order, especially when mediated to us in the fabulous forms of folk invention, has been overlaid by numerous layers of fancy—but so what? Everything we know about reality comes to us with a certain alloy of illusion, not accidentally but as a necessary condition of finite faculties. One does not need to be some dreary Kantian, or to believe that all experience is bounded by the supreme fiction of the synthetic a priori and the apparatus of perception, to appreciate that the intentionality of the mind and the testimony of the world become open to one another in a realm of symbolic representations. At the most primordial level of consciousness, the discrimination between the world’s self-attesting truth and the mind’s poetic creativity becomes merely formal. Even if one is so misled about the frame of reality as to think that the world Kirk describes is sheer delusion, again that is of no consequence. A vision of reality this amiable is endlessly preferable to the sheer metaphysical boredom of the materialist view of things and, for that very reason, makes a moral demand on any responsible soul; boredom is, after all, the one force that can utterly defeat the will to care what is or is not true to begin with. It is only some degree of prior enchantment that allows the eye to see, and to seek to see yet more. And so, deluded or not, a belief in fairies will always be in some sense far more rational than the absolute conviction that such things are sheer nonsense, and that the cosmos consists in nothing but brute material events in haphazard combinations.

Another way of saying this, I suppose, would be that the ability of any of us to view the world with some sort of contemplative rationality rests upon the capacity we possessed as children to see in everything a kind of eloquently articulate mystery, and to believe in far more than what ordinary vision discloses to us: a capacity that endows us with that spiritual eros that allows us to know and love the world, and that we are wise to continue to cultivate in ourselves even after age and disillusion have weakened our sight.

So, again, spare a thought for the soul of the good Rev. Robert Kirk, imprisoned in the great pine atop Doon Hill.

Get well soon! I'm sure that you know (but I must share it as it is such a quiet comfort to me through the long nights) that Origen (with his typical good sense) was a bold defender of what you call "quite another view that might have been extracted from the New Testament, the Pauline corpus in particular." Origen wrote in Contra Celsum (8.31) that "the water springs in fountains, and refreshes the earth with running streams" and that "the air is kept pure, and supports the life of those who breathe it, only in consequence of the agency and control of certain beings whom we may call invisible husbandmen and guardians." And Origen closed this point with: "but we deny that those invisible agents are demons."

thanks for sharing hope you make a quick recovery glad to hear mill bank learned his lesson hes far too smart to not greet n meet the woodland spirits