Extenuant vigiles corpus miserabile curae, adducitque cutem macies et in aera sucus corporis omnis abit. Vox tantum atque ossa supersunt: vox manet; ossa ferunt lapidis traxisse figuram. inde latet silvis nulloque in monte videtur; omnibus auditur: sonus est, qui vivit in illa.

[Her sleepless cares wear away her suffering body, and emaciate her skin, and her body’s moisture withers all away into the air. Only her voice and bones are left: her voice remains; her bones are said to have assumed the form of stone. Thenceforth she is hidden in the woods and is seen no more on any hill; she is heard by all: it is a sounding forth that has its life in her.]

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book III, ll. 394-399

§1

The planet’s human population at present exceeds eight billion souls—more than enough, one would think, to assure that we need never want for company. And yet, as a species, we have a remarkable gift for loneliness. So deep is our longing for communion with the world about us that nothing can entirely satisfy it, or even quell it for very long, so long as we suspect any dimension of reality might be indifferent to our overtures or incapable of addressing us in turn. Until very recently, of course, it scarcely occurred to us that such a thing was even possible. For most of our history, our instinct had been to view all of cosmic nature as the residence of mysterious and vital intelligences—gods and nymphs, daemons and elves, phantoms and goblins, and every other kind of nature spirit or preternatural agency—not because we were victims of the “pathetic fallacy,” and not because our evolutionarily engineered “intentional stance” had populated our landscape with personable mirages, but only because our nature dictates that we can never be at home in a world that does not speak. This is largely why we delight in fables about talking animals, and in stories that infuse inanimate objects with consciousness and personality, and in any other kind of tale that tells us there is a subjective depth in all things that knows us as we would wish to be known. Our proper habitat is an enchanted world, charged with mana or filled with fairies or kami, where we can always find places of encounter with immortal (or at least longaevous) powers; and in the absence of those numinous or genial presences we feel abandoned, and very much alone.

It is, however, only in the modern age—having done so much to drive those presences away, and to reduce the world to something intrinsically impersonal and dead—that we have really discovered how profound that loneliness can be. The history of disenchantment has been the history of our own long, ever deepening self-exile. So, naturally, no longer believing that the world hears us or speaks to us, we find ourselves looking elsewhere for those presences. We call out to the stars and scan the skies with enormous radio telescopes, searching for the faintest whisper of a response. We try to convince ourselves that our machines might become sentient. We dream of creating a virtual reality responsive to our needs in a way that the now spiritually evacuated world around us no longer seems to be. Even among many analytic philosophers, whose entire intellectual mission is to think as boringly about everything as humanly possible, perhaps the most fashionable theory of mind at present is panpsychism, which tells us that the material world may yet be in some sense full of life and intelligence after all.

*******

§2

Perhaps this, at least—the growing tolerance of panpsychism by Anglophone philosophers, that is—is something of a promising development. It still needs to be liberated from a number of lingering materialist prejudices; but one would like to think it might portend some slow epochal shift away from the cultural dominance of a mechanistic paradigm of nature. That, though, seems a remote possibility at best just at the moment, and on the whole our surrogates for those missing presences are fairly miserable compensations for what we have lost. When, two weeks ago or so, I likened our fascination with our computers to Narcissus bewitched by his own reflection in a forest pool, I mentioned in passing that he had been condemned to die from unrequited love because he had refused the amorous entreaties of the nymph Echo. I did not mention, however, that Echo also perished as a result of his imperviousness to her appeals. She was so lovelorn as a result of his rejection of her advances that, in the end, she vanished away, her bones petrified and her voice attenuated to a dying reverberation in desert places. I really should have included that part of the story in my lugubrious little diatribe; it would have made the central allegory all the better. At least, the conceit seems an elegant one to me: we turn to the thin, pathetic, vapid reflection of our intelligence in our technology for companionship because we have so sealed our ears against the living voice of the natural world that now nothing more than its fading echo is still audible to us. You see how well that works as an extended metaphor. At least, for me it might have captured some further dimension of the pathos of our situation.

*******

§3

Mind you, not everyone finds that situation as terrible as it truly is. There are even some who would like to deepen our loneliness. And why not? In a sense, silencing the voice of nature has always been very much the great project of modernity. For a very few among us—Daniel Dennett comes to mind—the most enchanting promise of that phantom we imagine haunting our technology is not that it might possibly possess real consciousness, but that it might help us to recognize that we do not: that we too are only machines who only imagine we are conscious beings in a living world. How peaceful it might be to be delivered from the invasions of a real world, insisting on being received by a real self. Then the silence would be complete. Even our own voices would become inaudible to us. We would know that nowhere at all is consciousness real—that nowhere at all is there a place of communion with real presences, not even with ourselves. It is an insane desire, of course; but perhaps it is not entirely inexplicable.

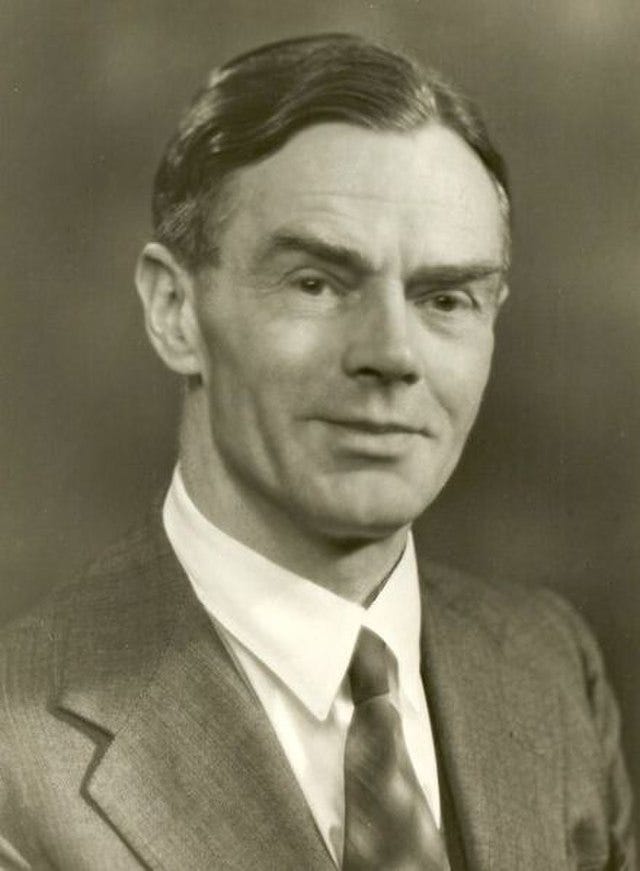

I believe I mentioned, in my remarks some weeks ago on the death of my friend Tom McLeish, that for some years he had been directing a project—in which I was a participant—on eclipses. The idea had occurred to him in 2017, when he and I were fellows at the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study and had both, from different parts of the country, viewed that year’s full eclipse of the sun, which had occurred on August 21st. I have to say, I had found it a remarkably moving experience. I had never observed a full solar eclipse before I, my wife, my son, and my dog had traveled to Nashville to see that one. Our view of it was perfect. We were able to watch it from beginning to end through a cloudless sky from a broad, open prospect atop a mountain outside town. In the city itself, rooftops and balconies and public parks were thronged with spectators, many of them deep in their cups well before the spectacle began to unfold itself on high; but, quite by chance, we had on the previous day discovered an ideal observation site: secluded, sylvan, but affording an unobstructed prospect of the heavens and wide open to the horizon on every side. We had taken all the proper precautions, needless to say. All three of us (Roland refrained from watching) were garishly bespectacled with deeply tinted lenses set in lime-green cardboard frames (though I also know that we all peered out from beneath them at constant intervals as the moon made its progress across the face of the sun). I was not at all prepared, I discovered, for the effect the event in its entirety would have on me. At first, I was merely stirred by the fantastic incursion of the lunar disk—now utterly black—upon the solar, and by the ways in which the colors of the world became increasingly unusual (the sunlight on the leaves and grass, for instance, becoming a kind of sullen amber, and the shadows cast by that light a kind of fantastic heliotrope).

It was at about the point when two-thirds of the sun were obscured, however, that the true uncanniness of the experience began to take hold of me. It was then, almost in an instant, that the entire sky began to change its aspect; visibly darkening, it acquired a strangely glassy quality, and then continued to deepen in hue till it had become a translucent cerulean directly overhead in the sky’s vault but a gauzy violet down at the world’s edges. Then, as the sun and the moon reached perfect alignment, and the former was reduced to a thin and ever so slightly prismatic nimbus around the latter, the dome of the sky began to become diaphanous and I realized with a start that the dozen or so soft gleams of light I saw hovering in its depths were in fact stars. In an instant, the canopy of the lower atmosphere had been withdrawn; for the first time in my life I thought I had some sense of what the Qur’an means when it speaks of the sky being rolled up like a parchment at the end of days; and it was a genuinely tremendous and dizzying sight. How could anyone look at such thing, I remember thinking, and not feel, at least fleetingly, as if the whole world were dissolving? In other ages, neither so disenchanted nor so sensually surfeited as ours, it must have been a truly terrifying experience. Even I felt a tremor or two of existential vertigo as I stood there gazing into the abyss of space through a suddenly crystalline sky, although I certainly had no fear that the frame of things was in any imminent danger of disintegrating. Then, after several minutes, the vision began to fade, the pallid stars melted away again into the brightening sky, the full circle of the sun gradually emerged again from behind the moon, and the ordinary fashion of the world was restored.

It took some time for me to decide what the entire effect of the eclipse on me had been—or, rather, the effects, since my reactions continued to develop and fluctuate for some time. Certainly the experience had been of something majestic and mysterious; I had been overwhelmed, astonished, and even vaguely alarmed when the stars above had become visible through the diluted daylight. Why this should have come as a surprise to me I cannot say, since it is an amply attested phenomenon of which I had been apprised many times in the past. Admittedly, several friends who had themselves witnessed full solar eclipses had all told me that they had seen nothing of the sort, and that for them the sky had remained obstinately opaque even when the sun had been fully obscured. Still, it was all there in the literature, again and again.

Diodorus Siculus, for instance, had included a mention of the stars’ visibility in his brief account of the eclipse of 15 August 310 BCE that had preceded the escape of the tyrant Agathocles with sixty ships from a Carthaginian blockade of Syracuse; both Plutarch (in “On the Face of the Moon’s Disk”) and Phlegon of Tralles (in the Olympiads) had recorded the same detail, the former in regard to one on 20 March 71 CE, the latter in regard to one on 24 November 29 CE; so had Marinus of Neapolis about one that occurred on 14 January 484 CE, in a passage from his Life of Proclus that I myself had once translated as a school exercise. Only a week before our sojourn in Nashville, moreover, I had begun skimming through a remarkably comprehensive compendium of eyewitness accounts, Historical Eclipses and Earth's Rotation by F. Richard Stephenson, and I had noticed that the same detail had recurred there with a fairly pervasive regularity throughout its pages. The very first account I had come upon in the book, in fact, was a brief mention of a solar eclipse (dated now as having occurred on 24 October 444 BCE) in the classic Chinese text Records of the Grand Historian (or Shīji), which had prominently mentioned the stars on high shining out in the middle of the day. Excerpts from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, the Chronicon Scotorum, the Chronicon of Andreas of Bergamo, the Historiae Byzantiae of Leo the Deacon, and any number of other annals and histories from antiquity and the Middle Ages had included frequent references to the phenomenon. There were, for example, an unusually large number of reports from across northern Europe of the solar eclipse of 2 August 1133, and not a single one of them, as far as I can recall, omitted mention of the starry firmament. The same is true of the various accounts by the Muslim and Christian observers of an eclipse of 11 April 1176 in Asia Minor, as well as of all three of the extant reports of another that occurred on 9 August 975 in Japan. And so forth and so on. And yet, even though I had acquainted myself with these facts just a few days earlier, I had still managed to depress my expectations to the degree that, when the stars in fact appeared, it came to me as a revelation.

*******

§4

It was only a week or so later, however, when I had further acquainted myself with old accounts of eclipses past, that I realized something rather curious. While my own experience of the stars becoming visible during the eclipse had in most obvious respects matched the descriptions of various ancient, mediaeval, or even early modern chroniclers, it had also differed from theirs in one very conspicuous way. Whereas all of them had remarked upon it, and some had noted the wonder and terror the sight of it had evoked among its witnesses, absolutely none of them had said anything at all regarding what to me seemed most immediately obvious about it: to wit, its ravishing beauty. As I say, I had felt a momentary sense of disorientation at the apparition of the stars, and that aforementioned vertiginous moment of amazement; but, more persistently and far more affectingly, I had been aware of the mysterious loveliness of it all—the stars like pale white diamonds, the sky like liquid glass, the faint iridescence surrounding the sun’s corona, the strange, shadowy, nacreous twilight that suddenly hung above the world. I had felt a genuine sense of gratitude for and delight in all of it, as well as a desire to dwell in the moment as long as I could. And that was what it would have first occurred to me to say about the experience if asked about it, and probably what I would have said last as well, and what I would have placed the greatest stress upon at any point. By contrast, all the reports that I read from the more distant past had been notable either for their dry tone of indifference or for the palpable air of horror pervading them. Those who mentioned the stars generally described their appearance as terrifying, or at least bizarre, and nearly all of them exaggerated the gloom through which the stars had shone out.

Now, needless to say, those documents come to us from a world considerably less, if not enlightened, at least illuminated than our own, and from centuries when the dark really was as often as not something to be dreaded, and when the night was often very dark indeed, and when the sun’s departure each day regularly disclosed a dazzling and unfathomable ocean of stars, far too sublime to inspire mere admiration unmixed with some element of fear. We who live in the glow of electric lights and who rarely ever see the naked sky at night can scarcely imagine what the ordinary difference of night from day felt like before gaslight and then its electric sequel began to dispel the shadows; but it only makes sense that in such a world the darkening of the sun and sudden appearance of the stars during the day should have seemed more ghastly than glorious. Whereas, to me, this shimmering glimpse beneath a veiled sun into the depths of space came as a rare and wonderful blessing, to most observers in previous ages the same experience must almost necessarily have seemed like something of a curse—something “disastrous” in the etymologically precise sense of that word—something, that is, “ill-starred.”

*******

§5

Obviously, we should be glad that today we can watch an eclipse not only without terror, but with genuine delight. Because it is simply a brute event for us, which we would not even know how to see as a portent of imminent doom or an omen pestiferum or a harbinger of civil calamity, we are free to exult in it as something rare and beautiful. But, granting this, we should not deceive ourselves that in this matter we enjoy a privilege denied our ancestors on account of our superior knowledge or our keener powers of reasoning. As I have noted, many ancient cultures were well aware of the mechanics—or, at the very least, the calculably mechanical nature—of eclipses, and entertained no doubt that they were entirely natural phenomena; and yet this in no way robbed eclipses of their dire prophetic significance for those cultures. What sets us apart from many ancient peoples in this respect has nothing to do with our sciences or our more “enlightened” view of things but everything to do with a set of metaphysical prejudices that we have absorbed from the culture around us. We may not be able to view the natural order as a realm of invisible sympathies and vital spiritual intelligences, but this is solely because our vision of reality is the product of four centuries of mechanistic dogma, which tells us that matter is something essentially dead, nature a machine, and the mind a resident alien within (or merely an emergent property of) an intrinsically mindless universe. But of course, as scarcely needs saying, these are not truths of reason or deliverances of the sciences; they have neither empirical nor theoretical warrant; they are merely the prevailing biases of our times, not only no more intellectually respectable than a belief in celestial signs and portents, but indeed a good deal less so, inasmuch as they are so wholly unreflective.

This is not to deny that there are good reasons to be glad of our deliverance from the terror of the night. The dark is our most ancient adversary, it seems fair to say, and throughout much of the earth we have vanquished it utterly. And yet, even so, it is worth recalling that our capacity for terror is more or less directly proportionate to our capacity for awe, reverence, or prudence; fear and piety, dread and elation, horror of the unfamiliar and moral restraint before the unknown are simply varying intensities along a single emotional continuum. If we were still able to believe that nature is intrinsically communicative, intrinsically eloquent—that she addresses us with warnings, admonitions, and auguries—perhaps we would be less able to violate, despoil, pollute, and destroy the natural world with quite the gay abandon that we do. It is hardly to our credit—and probably not at all to our benefit—that we no longer experience the cosmos as charged with intentional meaning, and no longer perceive either nature’s regularities or her anomalies as embassies to us from the mystery that lies within all things. Now nothing is inviolable to us, nothing sacrosanct; everything natural is merely a resource to be exploited or an obstacle to be surmounted or a burden to be shed. Not only are we spiritually impoverished as a result; we are rapidly murdering our world.

*******

§6

Which is why it is wise to remind ourselves as often as we can that there was a time when the world did speak, or when at least we believed that it spoke and, because we believed, it did in fact have a meaning of its own for us, already there resident within it before any we might choose to impose upon it. The natural order appeared to us as a system of intelligible signs, a language declaring more than merely itself, the overwhelming eloquence of some intelligent and expressive agency behind the visible aspect of things. Throughout human history, most peoples have assumed that, when we gazed out upon the world, something looked back and met our gaze with its own, and that between us and that numinous other there was a real—if infinitely incomprehensible—communion. Practically every sane soul presumed a “vitalist” and “panpsychist” model of the world. And, frankly, every truly sane soul still does, at least implicitly.

Explicitly, however, most of us have succumbed to the mythology visited upon us by the mechanical philosophy at the beginning of the modern period, and have learned to think of life as no more than a fortuitous and functional arrangement of intrinsically lifeless matter, and have grown ever more accustomed to living according to the logic of mechanism, within a machine of our own contrivance: philosophical, technological, economic, political, social. Having rendered the world mute—or, at least, having deafened ourselves to its entreaties and admonitions—we have reached a condition as a culture in which we feel no compunction in forcing it to serve whatever ends we will for it. Along the way, in order to preserve our vision of a dead world generating illusory meaning and beauty, we have had to extinguish the occasional counterrevolution—Romanticism, principally, and then each of its ever fainter, dying echoes—but in our late modern moment we really have achieved a cultural consensus, principally because our ubiquitously “technologized” form of life and the market economy it serves have now exceeded our power to resist it, except in the most trivially local and elective ways.

*******

§7

In the weeks following my experience of the eclipse of 2017, I have to admit, I found myself constantly retreating—reluctantly but inexorably—to the late thought of Heidegger. For him, modernity was simply the time of realized nihilism, the age in which the will to power has become the ground of all our values; as a consequence it is all but impossible for humanity to inhabit the world as anything other than its master. As a cultural reality, it is the perilous situation of a people that has thoroughly forgotten the mystery of being, or forgotten (as Heidegger would have it) the mystery of the difference between beings and being as such. This is simply nihilism, in the simplest, most exact sense: a way of seeing the world that acknowledges no truth other than what the human will can impose upon things, according to an excruciatingly limited calculus of utility, or of the barest mechanical laws of cause and effect. It is a “rationality” of the narrowest kind, so obsessed withwhat things are and how they might be used that it is no longer seized by wonder when it stands in the uncanny light of the inexplicable truth that things are. It is a rationality that no longer knows how to hesitate before this greater mystery, or even to see that it is there.

Admittedly, Heidegger’s narrative of our culture’s descent toward this nihilism is by turns astute and absurd, the latter being the case the further back into intellectual history he attempted to project its sources. Where he was certainly correct, however, was in recognizing that a crucial boundary had been crossed at that moment when the ground of truth came to be situated in the self that perceives rather than in the world that shows itself; and in philosophy this inversion of the order of truth probably achieved its first full emblematic expression in the decision of Descartes to begin his philosophical project as a rational reconstruction of reality from the vantage of the subject, erected upon the fundamentum inconcussum of his own certainty of himself: “I will close my eyes,” he says in the third Meditation, “…stop up my ears…avert my senses from their objects…erase from my consciousness all images….” But, if one begins thus, what world can possibly appear when one opens one’s eyes and ears again? Perhaps—at least, for many—only a fabrication and brute assertion of the human will, an inert thing lying wholly within the power of the reductive intellect. The thinker is then no longer answerable to being; being is now subject to him or her.

It is thus, according to Heidegger, that our age can be understood simply as the age of technology, which is to say an age in which reasoning has become no more than a narrow and calculative rationalism that no longer sees the world about us as the home in which we dwell, where it is possible to draw near to being’s mystery and respond to it; rather, it sees the world now as mere mechanism, and as a “standing reserve” of material resources awaiting exploitation by the projects of the human will. Now the world cannot speak to us, or we cannot hear it. Being’s mystery no longer wakens wonder in us; indeed, we habitually mistake that mystery for just another technological question: What physical forces produce which physical states? As the mystery of the world is not a thing we can manipulate, we have forgotten it. Not only do we not try to answer the question of being; we cannot even understand what the question is. The world is now what we can “enframe,” something whose meaning we alone establish, according to the degree of usefulness we find in it. The regime of subjectivity has confined all reality within the limits of our power to propose and dispose. More and more, our culture has become incapable of reverence before being’s mystery, and therefore incapable of reverent hesitation. And it is the effect of this pervasive, largely unthinking impiety that underlies most of the special barbarisms of our time. It is certainly what continues to drive us toward ecological destruction. But, again, we may well have passed that last moment when as a culture we still had any discretion regarding how the future will unfold.

*******

§8

At the same time that I found my thoughts turning to Heidegger, however, they were also turning toward Owen Barfield. He too constructed a genealogy of our lost awareness of the world as anything more than a brute mechanical event—a genealogy that at certain junctures is as grim as Heidegger’s, but also at other junctures more hopeful. For him, there was a kind of spiritual destiny for humanity that necessitates our current moment of dialectical separation from what he calls “original participation”—the immediate and unreflective communion with the mystery that declares itself in nature’s signs and portents—but only for the sake of an ultimate reconciliation with the world under the form of a more reflective, objective, and yet very real “final participation.” Presumably that final state would be more speculatively aware than the first, but would also involve a recovery of the reverence, restraint, wisdom, and love—though not the terror, perhaps—that once characterized our openness to the world.

I fear that this last phase of the story is in fact a very unlikely expectation, and Barfield simply had no notion how absolute our estrangement from nature had become and how swiftly it could bring about irreparable destruction. But it is consoling to think otherwise: to think, that is, that an escape from the economic and cultural machine in which we have imprisoned ourselves is still possible, and that we could yet make our technology (which is, after all, very much a part of our essence as human beings) a benign and healing presence within nature, and that we could even find our way back to the living world, once again attentive to its voice.

It would be pleasant to think, at any event, that we may one day recover the wisdom to experience every eclipse as a kind of portent—if not of some impending catastrophe or epochal transition, at least of that perennial mystery that it is a destructive madness to forget. If we are not able to do this, however, then in a somewhat ironically inverted sense every eclipse will still serve as an omen after all, whether we acknowledge it or not: and that an omen of the greatest disaster imaginable.

I've always found it by turns wonderful & puzzling that our planet's moon should just happen to be, when viewed from earth, the exact relative diameter of the sun (well, 96%). (At least for now—check back in 50 million years.) On most planets, a moon would either engulf or barely speckle the sun as it seems to pass before it. It's a very strange coincidence.

When I saw the eclipse—this is absolutely true—three eagles flew right overhead once the light returned.

I naturally interpreted this to mean that the republic would fall and three emperors would arise in rapid succession.