Thoughts In and Out of Season 11

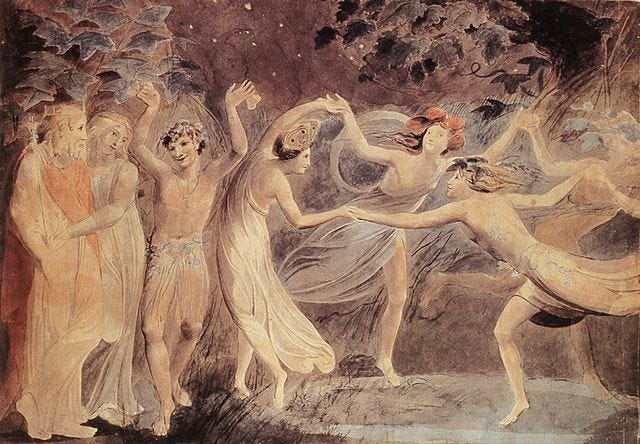

Fairies again (don’t worry, that won’t become a running theme), anacyclosis, post-social humanity, Kirkian “conservatism,” another haunted Japanese forest (which just might become a running theme…)

§1 The downstairs sitting-room of the house in Howard County, Maryland in which I grew up had a large fireplace, a pair of French doors opening out into a back yard bordered by lilac-bushes, a piano, and numerous bookcases filled with volumes that had flowed into our household from various tributaries, including the haphazardly acquired collections of several previous generations of the family. There were many treasures there that I suspect even my parents had forgotten they possessed, among them a few exceptionally handsome first American editions of John Ruskin and Lafcadio Hearn and a small illustrated copy of Paradise Lost that was a model of the bookmaker’s art. There were also a number of books whose presence made no particular sense at all and that were clearly there purely as a result of happenstance; and among these latter were two copies of the autobiography of William Allen White. I mean no disrespect to the memory of that eminent editor and journalist—not to mention redoubtable champion of progressive Republican and Progressive Party causes in the years leading up to the Great War and during the period entre deux guerres—but even a single copy of his memoirs was a little out of place among the somewhat more elevated texts that surrounded it. When I was a boy, however, I had no idea who White was; I knew only that I had heard him mentioned respectfully by Sheridan Whiteside—that is, George S. Kaufman’s and Moss Hart’s lampoon of Alexander Woollcott as played by Monty Woolley in the film version of The Man Who Came to Dinner, in case I am being obscure—so I thought he must be someone important and decided to give the book a try when I was about thirteen or so. I did not get very far, but I got far enough to come across the only passage that has stayed with me (which also happens to be the only passage I have ever seen reproduced by anyone else). It tells of something that happened to White when he was 23, on his last night in his home town of El Dorado, Kansas (a place I think it fair to assume does not quite live up to its name); the next morning he was to leave to take up a position at a large Kansas City newspaper, and so had spent the evening out and about, bidding farewell to friends. The passage stands out from the rest of the book chiefly by virtue of actually being interesting, but also by virtue of being bizarrely unlike anything else ever penned by that genial but hardheaded and practical Bull Moose stalwart. Here it is (pp. 93-94):

One other thing I remember—a strange thing and quite mad. The August harvest moon, under which a few night before I had come home feeling most poetical from my day’s fishing with my visiting editors, was still shining high in the sky when I walked home another night, …not unconscious of the night splendor. I turned in and slept deeply. Then I remember waking up, when moon’s beams were slanting and the dawn must have been but two or three hours away. Now this is sure: I did wake up. Something—it seemed to me the sound of distant music—came to my ear. The head of my bed was near a south window and I looked out. And I will swear across the years during which I have held the picture, that there under a tree—a spreading elm tree—I saw the Little People, the fairies. I was not dreaming; at least I did not think so then and I cannot think so now. They were making a curious buzzing noise, white little people, or gray, three or four inches high. And I got up out of bed and went to another window and still saw them. Then I lay on my belly on my bed and kicked my heels and put my chin in my hands, to be sure I was not sleeping, and still I saw them.

For a long time, maybe five minutes, they were buzzing about, busy at something, I could not make out what. Then I turned away a moment, maybe to roll over on my side or to get upon my knees, and they began to fade away; an instant later they were gone. And there I was like a fool, gawking at the bluegrass under the elm. I got up and sat in a chair. I was deeply upset, bemused, troubled. I thought: “Maybe I’m going crazy!” I knew well enough of course even then that what I saw I did not see, but when you are cold sober and have the conviction spread over you that you are made, you are bothered—and I have been bothered ever since. It is not impossible. Nothing is impossible. Many years later I heard of transparent fish—with other eyes, other creatures see other things; with other ears they hear much that escapes our human ears. Perhaps in our very presence are other beings like the transparent fish, which we may not feel with our bodies attuned to rather insentient nerves. Heaven knows! For an hour I thought I was crazy. And when I recall that hour and am so sure that I was awake, I think maybe I am still crazy.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Leaves in the Wind to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.