Thoughts In and Out of Season 8

Entropy and negentropy, labor markets, after Christendom, ecology and myrmecological ethics, calling the dead...

[Free this week, incidentally.]

1. As you may know, Clerk Maxwell’s “demon”—like Laplace’s—is a superlatively percipient little imp who inhabits the microscopic realm and knows the position and speed of every particle to be found there.

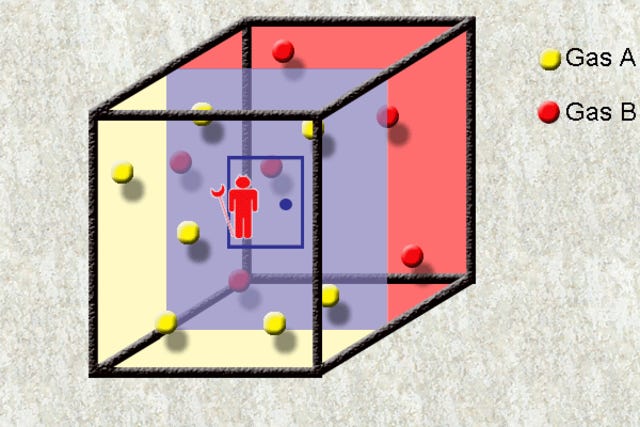

He, however, unlike Laplace’s demon, is not interested in reconstructing the physical history of the universe or in foretelling its future from the current dispositions of its atoms; rather, his particular concern is to defeat the second law of thermodynamics (wretched little subversive that he is). To this end, he creates an enclosed cell full of gas and divides it into two chambers by an impenetrable partition, in which he then installs a small gated aperture just large enough to admit a single molecule at a time from either side to the other; this he uses to segregate faster from more slowly moving molecules so that the two chambers come to have distinctly different temperatures, which allows for a motor of sorts to be run off the resulting heat gradient. Thus chaotic molecular motion is transformed into orderly mechanical motion, et voilà, entropy is not only held at bay, but converted into purposeful work at no thermodynamic cost, all through the skillful application of what is generally today spoken of as “information”: that is, negentropic order that allows for a controlled flow of the energy in dynamic systems. There was a time when Maxwell’s demon was nothing more than an especially galling thought-experiment; in mainstream physics there could scarcely be a more truly scandalous—a more truly demonic—perversity than suggesting that the universal reign of entropy could be thwarted. In the realm of biological “informatics,” however, the little fellow has come to enjoy a new degree of fame as the life-sciences have come better and better to appreciate the peculiar negentropic properties of organic life and its intricate homeostatic systems. Lynn Margulis—the great evolutionary biologist associated principally with the study of symbiogenesis—once predicted that a century hence the orthodox Neo-Darwinian synthesis would come to be viewed as a quaint superstition, preserved long past its natural term by sheer dogmatism; and, with every advance in the field of “systems biology,” it becomes harder to deny that she may have been right. Certainly, it seems that a more complicated theory of evolution is called for now that it has become all but impossible to deny that all organic life consists at every level, from the cellular to the social, in elaborate hierarchies of integrated intentional systems. At present, therefore, a great deal of the focus of the biological avant-garde is upon information—upon, that is, those somewhat occult organizational properties that have the power to reduce uncertainty and to constrain energy use in homeostatic systems “far from equilibrium.” I have to say, however, that the more I read about the causal significance of information—or the “flow of information”—the more difficult I find it to see how it can be written into the laws of physics, as some claim it must, and the more convinced I am that it can be written into the laws of biology only in terms of a cosmic organicism. That is, I have come to think that Robert Rosen may have been right to say that life will remain unintelligible to us so long as we insist on treating physics as the general paradigm of all the sciences, of which biology is only one special expression; rather, we shall need to reconceive biology as our general paradigm, whereof the laws of physics are a special set of mere limit-conditions. I have also come to think that, if the laws of information could be “discovered,” they would prove to be fundamental rather than emergent, would have to be characterized as logical or metaphysical rather than nomological necessities, and would look quite a lot like formal and final causality.

2. I had occasion to think of Maxwell’s demon in an entirely different context a few weeks ago when I had the misfortune of seeing a screenshot of a “tweet” by a professed “National Conservative” claiming that globalist capitalism wants nothing more than the erasure of all national borders so that “cheap labor” can flow unobstructed from land to land. I am not sure in what school of economics the author had learned his understanding of these matters, but one would think that even the most paranoid blood-and-soil chauvinist could not possibly be dimwitted enough to imagine that corporate capitalism seeks either the elimination of the nation state or a genuinely unregulated labor market. Corporations may often desire liberation from the “heavy hand” of the state, but of course they also rely entirely upon the laws and coercive resources of the state, its powers of negotiating and enforcing trade agreements, its policing of societies either exploited or left behind by the market, its stable currencies, and most certainly its borders. Far from seeking to impose the “iron law of wages” on some kind of boundless international labor pool—which would, of course, be an environment in which a “labor international” movement might actually be incubated—corporate interests require a controlled flow between segregated “labor markets” in order to maintain the homeostatic structure of production and consumption within the dangerously entropic economic landscape of late liberal capitalism, and as far as possible to exploit the “temperature gradient” between richer and poorer economies to convert industrial decline into an engine of profit. Then again, perhaps for the same reasons, late modern capitalism has considerable use for the sort of nonsensical narratives that National Conservatism promulgates. It is obviously not the case that the unskilled labor that as a rule enters the US by way of the southern border has anything to do with the constant contraction of the skilled working middle class in formerly thriving industrial regions; but, of course, it is convenient for the disappointed, disaffected, and disregarded to believe that it does.

3. What’s bred in the bone will not come out of the flesh (which, incidentally, is the correct quotation). I am not a Hegelian (perish the thought), but I am something of a fatalist with regard to the dialectical disclosures of history and the irreversibility of its rational verdicts. That much of the System I find it difficult not to accept, though only as a nomological rule of method rather than a metaphysical rule of nature. At least, I believe that the course of history exhausts the possibilities of human existence that it successively embodies and that it renders their recurrence impossible precisely by demystifying the rational content it makes available to “spiritual” reflection. For, once purged of its empirical residues and extracted from mere contingency, that content becomes almost perfectly immune to naïve credulity; and I take this to be a law not merely of private ratiocination, but of cultural sensibility. A society becomes incapable of any innocent return to the convictions and intellectual habits and moral appetites of the past not because its members are consciously aware of the difference between those vanished forms of historical existence and logically necessary material conditions, or even between custom and nature, but simply because the ubiquitous values and conceptual paradigms of the present have been shaped in part by a shared rejection of those of the past. As I have noted before, whatever takes leave of a culture as faith can return only as irony. In negentropic systems, “information” constrains the future by regulating a flow of energy; and history’s dialectic, in the same fashion, constrains the future by determining the flow of cultural creativity. Then again, it is also true that what survives from one epoch to another is only that which can be assumed into the emergent cultural consensus on the latter’s terms; and so its continued survival is bound to the fate of that consensus. When the Christian cultural order departed, for example, it took with it also the last vestiges of the pagan order that had preceded it; it was impossible at that point that the modern consensus that succeeded Christendom could ever involve a true recovery of the values of either the Christian or the pagan past.

4. I mention this in part because, as I watch Integralists and National Conservatives vie with one another for the privilege of articulating the principles of the “postliberal Christian future”—even though neither faction is either genuinely Christian or genuinely postliberal—I find it hard not to think that it is all rather like watching two junior officers aboard the Titanic fighting for control of the helm just as the band on deck is finishing the final refrain of “Nearer My God to Thee.” The “postliberal” future will not be a Christian order of any kind; that is written in the book of fate as surely as anything could be. With the passing of the great late liberal consensus of the past century or so, those last tenuous traces of Christian values that liberalism has preserved in itself—mostly a diffuse collection of moral sentiments, ideals, and leniencies regarding the inherent dignity of persons—will in all likelihood disappear as well. What certainly will not happen is a reversion of late modern culture toward some great fascination with or hunger for the dogmatic, institutional, or social order of the Christian centuries; very few want anything to do with any of that, and those who do have only the haziest notion of what it really was. The postliberal age will be all the more irreversibly post-Christian. The vital powers of Christendom are now entirely spent. Some far rougher beast is on the way just at the moment, and the Integralists and the National Conservatives are simply some of the more pathetic of its idiot accomplices. What might yet perhaps be recovered, however, is something of the more radical, more uncanny, much more “gnostical,” far more uncontrollably diverse, and considerably more anarchic aboriginal Christianity that the Great Church tradition ceaselessly strove to purge from itself or consign to its margins (where the books of such exotics as Eriugena or Cusanus were shelved), and that, as a consequence, did not suffer the fate of Christendom. Not only is that Christianity not an exhausted historical possibility; it scarcely ever entered into history to begin with.

5. Though the accelerating process of secularization may be the most resplendently conspicuous sign of our times, it is not a single phenomenon. There are diverse cultural expressions of the decline of faith, which perhaps correspond to differing kinds of unbelief—differing post-religious sensibilities, so to speak. There is secularization as a positive ideological project, the constitutional alienation of throne from altar, and the demotion of the latter first to a mere support for—and then to a private sphere wholly excluded from—civil society: a process largely extrinsic to the experience of faith. There is also the secularization of true disenchantment, a progressive and initially reluctant atrophy of belief, which can take shape only within the experience of faith, and only in proportion to the conviction with which that faith was originally held. There is also the secularization born of sheer indifference to faith, and of a consuming preoccupation with entirely different orders of desire, and with more proximate and immediately enticing objects of the will—which is perhaps especially typical of late capitalist culture. And, needless to say, there is secularization as the militant refusal of faith, and of hostility to its every claim upon the attention of society. All are known to us as both social and psychological truths, about both our age and ourselves; and, in actual practice, as neither social nor psychological realities can they be neatly discriminated from one another. But each arguably indicates a very particular aspect of the relation of modernity to Christian history, and—much more significant—a very particular dimension of the internal dynamisms of Christianity itself. The latter is worth trying to think through.

6. As the debt ceiling “crisis” unfolded earlier in the year, I found myself wondering why the idea of curtailing the whole absurd little contretemps through an invocation of the fourteenth amendment seemed so exotic even to most legal theorists. Precisely why it is now in the purview of congress either to raise or not to raise the ceiling is entirely inexplicable to me. The constitution explicitly states that the validity of the debt may not be questioned, which would certainly seem to imply that once the congress submits a budget it has already irrevocably and unimpeachably determined the altitude of the government’s legitimate debt. That can be stated in a modus ponendo ponens way, but I doubt there is any necessity for that. By the letter of the law, the budget is a structure that comes with its own ceiling, obviously, and the very act of voting on whether or not that ceiling is valid is already to have violated the law. If there are any jurists out there among the readers of this newsletter, please feel free to explain it to me; because the process as it currently operates is absurd.

7. As a result of finding myself unexpectedly trapped in a waiting room some weeks ago, I spent an hour and a half skimming through the only book on the table there that had nothing to do with self-help or ripped bodices. It was E.O. Wilson’s The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth, which appeared in 2006. It is a curious volume, to say the very least. I mean to say, when Richard Nixon made his epochal visit to China, it was generally acknowledged that he was able credibly to pursue rapprochement with Mao’s regime precisely because he was the last person on earth who would have sought it on ideological grounds; his credentials as an implacable enemy of communism were beyond any doubt. Nevertheless, he understood the subtleties of diplomacy well enough to realize that his embassy would still in all likelihood fail if he were to interlard his appeals for greater amity and cooperation with occasional gratuitous insults—say, mocking his hosts for their country’s technological backwardness, abominating their political system, addressing the Chairman as “Mr. Fu Manchu,” speaking in a lampoonish Chinese accent, or venturing racist witticisms about laundries. And this, I think it fair to say, was evidence of a certain wisdom on his part. I imagine it is an all but infallible rule that, in attempting to convert an adversary to one’s side or to entice a skeptic to join one’s cause, it is best not to pause with a certain predictable regularity to inform him that you see him as a ridiculous simpleton or a heartless savage. It might be regarded as rude, you see. This is a rule, however, with which Wilson appears to have been unacquainted. The Creation was, after all—allegedly at least—an attempt to forge an alliance between scientists and evangelical Christians (which Wilson seemed to assume are of necessity mutually exclusive camps) for the sake of saving the ecology of the planet, with all of its marvelous and still only slightly explored biodiversity, from the devastation being visited upon it by our technologies, our populations, and our habits of life. This was obviously an admirable aim, and there was nothing in the least implausible about it. But there most definitely was something implausible about it being proposed by E.O. Wilson, given his long record of supercilious and infallibly vacuous remarks about religion. In his day, Wilson was every bit as preeminent as Richard Dawkins in the gallery of minor scientists who unaccountably mistook themselves for gifted philosophers and moralists. In a sense, of course, this should have rendered his good intentions in addressing the Evangelical community (like Nixon’s in visiting Mao’s China) utterly indubitable—but only so long as he could remain on his best behavior. Apparently, though, that small but vital condition never occurred to him. At least, he seemed to think it wise, in the course of making his appeal to Evangelicals of good will, constantly to depart from his exhortations to compromise and common purpose to inform his intended readers that their beliefs were not only entirely contradicted by all the scientific evidence, but patently preposterous (and really rather moronic).

8. Not that Wilson necessarily understood the likely effect of his words. His gift for innocent pomposity verged upon the miraculous, and he certainly seemed to believe that his professional portfolio contained some sort of license to pass peremptory judgments not just on Evangelicalism (with which he did have considerable personal acquaintance in childhood), but on just about every religious, philosophical, social, and ethical question, whether or not he had ever made any particular effort to understand it. Why he thought this is somewhat difficult to say. True, he was an entomologist of considerable achievements, and was generally regarded as the world’s leading expert on ants and all things formican; but this—substantial achievement that it no doubt was—still constituted a fairly meager scope of proficiency, soberly considered. I mean to say, has any other man ever presumed to condescend so grandly from so slight an intellectual eminence? More to the point, has any other specialist in so confined a field mistaken his expertise for a privileged vantage upon existence as a whole? For years Wilson was among the most voluble proponents of sociobiology, far and away the most logically incoherent theory of human behavior to have arisen in the academic world in many decades (basically, it was simply “the selfish gene” in an earlier but equally stupid form). And in books like Consilience he advanced arguments for a unified science of behavior—insect, reptilian, mammalian, human—with an altogether intoxicating blend of rhetorical brio and philosophical slovenliness. At no point in his career, it seems, had he thought to rein in his flamboyant arrogance long enough to ask himself whether he actually possessed the training or the erudition necessary to deal competently with the problems he imagined could be solved with sufficient attention to ants. I do not mean to be unjust. Wilson genuinely was an accomplished scientist—much more so, in concrete achievements, than Dawkins, for instance (whom Wilson once dismissed as a “science journalist”). But, as a thinker on many of those philosophical and moral issues he liked to write about, he often came across as a rank mediocrity, gaily ignorant of how frequently he was reducing complex issues to cartoons of themselves. That is not an unpardonable offense, of course. We are all liable to moments of egotism and self-deception. But there was something positively surreal in Wilson’s certainty that, by virtue of his mastery of the science of ants, he clearly knew human beings better than they knew themselves. It is hard, in long retrospect, to view with equanimity his evident conviction that anyone who doubted his estimate of his philosophical competencies, or failed to grant that his myrmecological accomplishments had provided him the key to all social truth, was a slobbering imbecile. And that conviction again and again rises to the surface of The Creation.

9. Still, Wilson did apparently think he knew how to appeal to those poor dunces who had never escaped—as he had done—the fever-swamps of faith. The book is written in the form of a letter to a fictional Evangelical pastor—or at least it is supposed to be. Wilson obviously found the epistolary conceit difficult to maintain with any constancy; at best, it flickers through the pages of The Creation; most of the time, it feels as if Wilson had forgotten it entirely while actually writing the book, and had returned to it almost as an afterthought. But, that aside, the book was intended for an audience that Wilson thought he understood. He had been raised among fundamentalists, which no doubt accounts for the tone of barely concealed disdain that recurs at the oddest junctures in the text. Yet he seemed to believe he still felt a certain sympathy or faint affection for the world of religious imagination Evangelicals inhabit, and clearly thought he knew how to address them. Actually, the book is far easier to enjoy if one generously ignores the religious aspect of its argument altogether. Wilson may indeed have harbored a few fond memories of warm Southern mornings in the pews, swaying to the cadences of impassioned sermons, but time had clearly somewhat dimmed his memories of Evangelical culture (Evangelicals do not actually, for instance, like being told that they are stupid). As far as I can tell, the sole feature of his childhood faith that he seems to have retained was his fundamentalism: that is, his firm and oft-expressed conviction that either the world was created by God or life developed on earth by evolutionary processes. And this, needless to say, somewhat limited the common ground he hoped to find with his readers.

10. On the other hand, the book is not without certain genuine merits and charms. Wilson was always at his best when he devoted his energies to descriptions of the variety and splendor of the natural world, its riches and mysteries, its magnificence and tragic fragility. And so it is in The Creation. In certain passages, an enchanting, almost mystical romanticism breaks through the surface of Wilson’s prose, his tone of contempt vanishes, and one even begins to feel something of his deep pastoralist nostalgia for the green world that (as he movingly argues) shaped the human psyche at its profoundest levels in the dawn of the race. As a purely popular scientific document, the book excels at making clear the cost of continued ecological degradation, to us and our fellow creatures: the precious species that will be lost, the sheer wealth of medical discoveries that will not be made if the rainforests and other varied habitats perish, the mysteries of land and sea that will never be penetrated, the lives (human and animal) that will be forfeit, the landscapes that will be ruined, and so on. At times, admittedly the book gives the impression that Wilson’s principal anxiety was that the planet’s biodiversity will be so radically depleted that scientists like him will be starved for new discoveries; but it is clear that, when he looked beyond his microscope, he genuinely descried a world of startling, beautiful, and (to a surprising degree) unexplored abundance that is, at present, caught in the slow convulsions of a massive extinction rate, of a sort the world has not suffered in many millions of years. It is difficult to argue with the facts and figures Wilson amassed.

11. The solutions he contemplated, however, are another matter. Any number of enormous changes in our manner of living, of course, will be necessary if we are to have any hope of averting the catastrophe we seem intent as a species on bringing to pass; we will surely have to create technologies for environmental restoration; we have to hope for concerted political efforts to produce laws at once practicable and effective; and so on and so on. All of this is as obvious as it is unlikely. But Wilson’s chief proposal (expressed in The Creation with a certain rhetorical furtiveness) was that we must control the human population, and that—not to put too fine a point on it—is impossible except by the most coercive of measures. As a rule, moreover, those who make such recommendations tend to think that certain populations are more in need of pruning than others (not that I am accusing Wilson of that). The world is only so large, of course; Wilson was right about that. And it is not exactly a fantastic suggestion that, demographically speaking—at least, given the way we live now and the rapidity with which we are destroying the ecosystem—less might be more. But there are a number of perfectly conscientious environmentalists who have cogently argued that the human misuse of the environment springs more from the nature of our technologies than from the number of souls among us, and that the economic consequences of demographic decline might very well lead to an even more severe and precipitous decline in the wellbeing of the natural order. As the saying goes, the two greatest obstacles to effective environmental policies are great wealth and great poverty. Whatever the case, Wilson was an implausible participant in the debate over demography. As one of the fathers of sociobiology, his credentials as a moral theorist were—to say the least—unimpressive.

12. The Japanese phrase kaze no denwa (風の電話) means “wind-telephone” and refers to a phone booth, ideally but not necessarily installed in a garden, with no connections to any physical telephone lines. Its purpose is communication with the dead. That is not to say that it is a medium of interlocution with the deceased; the idea is not that one should use it to receive messages from the other side. Rather, one merely uses it to talk to someone who has departed this life, expecting no reply. The first such booth was built in 2010 by a landscaper and gardener named Sasaki Itaru for his own garden in Ōtsuchi on Honshu as a way of dealing with the loss of a cousin to whom he had been extremely close all his life. He intended the booth for only his own use, but the following year brought the great earthquake and tsunami in Tōhuku, and Sasaki-san opened his wind telephone to the public, as an aid for the bereaved. It has received many thousands of visitors since then, and other such booths have appeared not only in other parts of Japan, but in various countries all around the world. My only thoughts are “How wonderful,” “How Japanese,” and, needless to say, “It works, of course.”

{All images from Wikimedia Commons.}

As some Marxist or other pointed out recently, a shepherd in Burkina Faso leaves hardly any ecological footprint, while the CEO of Exxon leaves a global ecological footprint. It's not the number of humans, but what they do that matters—or to be more precise, it's where they fit in the system for which the planet is nothing but a profit engine.

Thank you. Wonderful, as ever. Your discussion of systems biology and mention of Robert Rosen leads me to ask, as I’ve wondered for some time, whether you’re familiar with and what you think of the work of Michael Levin (who’s recently been in several conversations with Iain McGilchrist).

Levin shows that morphogenesis is an intentional process and provides many examples of top-down causation and, of course, yet further compelling evidence against genetic reductionism.

- Caterpillar memories are retained in the butterfly, even though its brain is liquified during metamorphosis.

- A decapitated planarian’s regrown head and brain will retain its memories from before decapitation.

- Planaria can modulate specific genes to quickly adapt to survive in previously fatal environments that it had never encountered in its evolutionary history.

- Organs can develop into the same ‘target’ anatomy despite internal perturbations, even if they have to utilize different molecular mechanisms.

- Limb regeneration can be induced in animals that don’t otherwise regenerate just by changing their bioelectric ion channels.

- Xenobots, and self-reproducing Xenobots

All of it raises the obvious question of ‘where’ these memories and instructions are located that drive morphogenesis, and it looks increasingly like it’s somehow, at least sometimes, in the form of the thing the creature will become.

(One of many presentations can be found on YouTube by searching "Michael Levin | Cell Intelligence in Physiological and Morphological Spaces".)