Blessed Boxing Day

As the winter winds do blow...

§1: Wassail, wassail

Christmas is a feast of twelve days, beginning on the 25th of December and ending on Twelfth Night, Epiphany Eve, the 5th of January (at least, for those of us on the Gregorian Calendar). I mention this not because it is especially obscure knowledge that needs to be drawn up into the light, but because of the low-church Protestant confusion that has taken root in certain quarters of our culture, especially among Evangelicals, that there is a single ‘Christmas Day’, after which the festivities of the season—both sacred and profane, to draw an arguably anachronistic distinction—should soon come to a close. There are even those who subscribe to the heathen superstition that they should take down their trees before New Year’s Eve. Mind you, these same benighted anthropophagi generally put the trees up at Thanksgiving, assuring that their needles will be dry and dangerously combustible by the time the Feast of the Nativity descends upon them like a striking hawk.

Well, I am sure you good souls are not subject to these wicked delusions. You know full well that today is the second day of Christmas, and that there are ten more days to come. In Britain and the Commonwealth countries this is still Boxing Day, a name reflecting the custom of taking around presents and sweets and savories in boxes to persons who might be in need of them. At least, that is the traditional explanation, though some believe the origins go back to the practice of distributing the contents of the alms box to the poor of the parish on the second day of the feast. Whatever the case, it is also the feast of St. Stephen, a day traditionally associated with eleemosynary obligations, at least in ages past. Today, alas, it is observed mostly as a bank holiday, which more and more has come to mean a day of shopping for special deals. You, however, will certainly not give in to these blasphemous practices, I just know it in my heart. You will keep the feast unadulterated and unprofaned. You will wassail and revel, pray and worship, fill boxes with inedible fruitcake for the less fortunate and then force it upon them as your sacred duty and their dismal lot in life. Above all, you will keep your trees alight and spangled till the dark of Twelfth Night. And should any of you think to shirk your duties, remember that Father Christmas is watching you. (That’s an Orwell joke, by the way.)

*******

§2: T-minus twelve (roughly speaking)

Some of you may be aware, of course, that Christmastide in the West can be reckoned as being as long as fifteen days. Perhaps you have come across this curious fact in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, for instance. There the explanation may be that Christmas was sometimes celebrated from the 16th or 17th of December to New Year’s—though that is a theory of a single scholar, going on somewhat ambiguous textual clues, and may or may not be so. What definitely is the case is that Epiphany—or Theophany, as it is called in the East—is not properly speaking the commemoration of the Magi bringing gifts to the infant Christ, but rather a festal season comprising all of the revelations of Christ’s divine nature up to the inauguration of his mission from Galilee to Judea, beginning with his baptism in the Jordan and the disclosure there of his divine paternity and of the sending of the Spirit. In the West, though, Christ’s baptism is celebrated on the first Sunday of Epiphany, which can extend the official Christmas feast by as much as three days. Or so I believe. I don’t know if the arithmetic works and I am too lazy and debauched to check. To be honest, by the time Twelfth Night rolls around, any good honest Christian should be so deep in his or her cups and so sated on venison and goose and mincemeat as to have lost track of such things. One just has to rely on the Church here and hope they know what the hell they’re talking about (except when talking about Hell).

*******

§3: Going down to the river

While we are at it, my favorite celebration of Epiphany (or Theophany) is that of the Ethiopian Tewahedo, where the feast is called Timkat and involves a somewhat exuberant reenactment (of sorts) of the baptism of Christ. It starts with a wonderful procession with those gorgeous brocaded parasols that are the most distinctive liturgical ornaments of Ethiopian Christian worship and culminates in several of the faithful jumping into a large body of water (or, at least, going down into the waters).

But I am getting off track; today is still Boxing Day, so I will set my reflections on Timkat aside for now.

*******

§4: Who killed Cock Robin?

Though it is not in fact a robin, but rather a wren, whose death we mark and mourn.

One of the odder and seemingly vestigially pagan practices once observed in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, England, and the Isle of Man by peasantry and villagers on St. Stephen’s Day was the Killing of the Wren. (Of course, as with all such customs, we really have no idea how great its antiquity truly is, but we are going with the standard account that it was widely established in the British Isles in the Middle Ages, with folk origins lost in the mists of pre-Christian times.) I have to say, some aspects of mediaeval peasant piety strike me as a wee bit grisly (I say that not meaning to give offense to any of you out there who happen to be mediaeval peasants). On this day—Boxing Day, the Feast of Stephen—beaters would roust wrens from their warm repose in hedges and bushes, whereupon hunters—that is, boys and men armed with sticks, stones, and steely hearts—would launch their armaments into the air. Once one of the poor little birds had been successfully murdered, its corpse was hung upon a branch of holly or furze and then borne door-to-door by the dissolute mob of savages who had killed it, all to the accompaniment of Christmas carols, followed by bold demands for emoluments and food and drink. Apparently in those days there was thought to be no better inducement to ‘spontaneous’ generosity than the sight of a dead bird dangling from a stick; I suppose it was intended as a subtle message. This may be how caroling began, in fact, but who really knows? These days carolers are less numerous than they used to be, to the relief of many, so my memory may be playing me false; but I am fairly sure that none of the ones that I recall from my childhood ever menacingly waved an expired wren at me or my family, or in any other way suggested to us that we had better pay up if we didn’t want to end up sleeping with the birdies. Mind you, the threat of another carol was frequently more than enough to send us dashing to the kitchen in a desperate search for mulled cider and gingerbread to throw at them.

Anyway, back in the day—the Middle Ages, I mean, or the dimmer past—St. Stephen’s ‘festivities’ would conclude with a funeral. The wren who had been slain (for the purification of the people?) would be deposited in a small handsome coffin and then, amid many litanies and threnodies, and perhaps a lachrymose panegyric or two, buried in the parish churchyard.

Ancient lore, moreover (which very well may have been invented in the twentieth century), says that there is some connection between the Killing of the Wren and good harvests in the coming year. If this is true, I suppose I must grant that it is probably a better practice than the burning of a human victim in a wicker man or something of that sort, at least as long as you’re not a wren yourself. And apparently a feather plucked from such a wren is a powerful charm against storm and shipwreck at sea when worn in a sailor’s cap.

[Update: Apparently, the Killing of the Wren is a custom that persisted in some places to a far later date than I realized. Here is a link to Tommy Makem and the Clancy Brothers reminiscing and singing about the practice as they knew it in their childhood.]

*******

§5: A Poke in a Pig

By the way, another of the popular explanations of how Boxing Day got its name—which is as implausible as such explanations always tend to be—is that at one time alms for the poor were deposited through coin slots in little clay boxes affectionately called ‘pigs’, which were broken open on St. Stephen’s Day. This, so the story goes, was the origin not only of Boxing Day, but of the piggy bank.

*******

§6: Maryland, My Maryland

Another traditional sanguinary celebration of St. Stephen’s Day in various places is the Christmas Foxhunt, which is a very disagreeable custom indeed. It has long been observed in my neck of the woods, both among the civilized Cavaliers of Maryland and the barbarian Cavaliers of Virginia. Thankfully, the actual ‘hunt’ and ‘fox’ aspects of the ritual are now often omitted in Maryland and even sometimes down in the wilds and swamps of Virginia; these days it is usually observed in the form of a leisurely chase without quarry over old hunting trails. That is as may be.

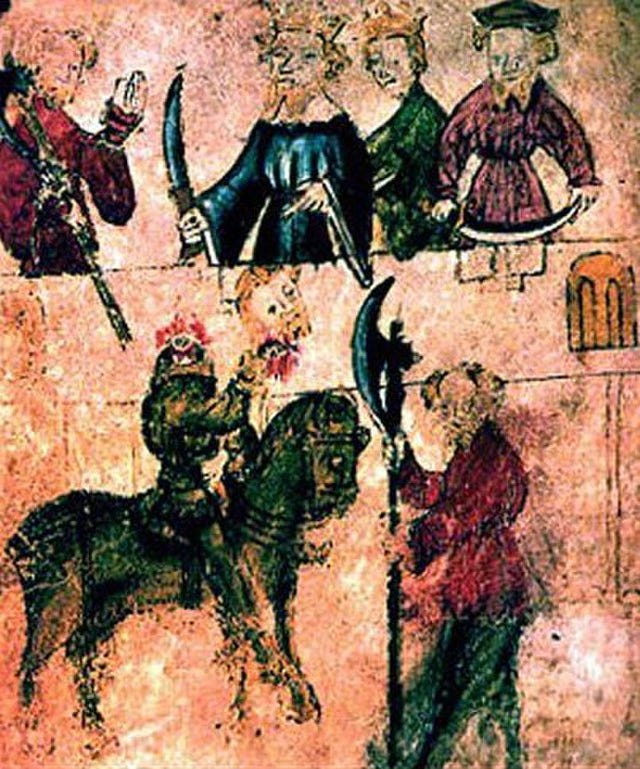

More interesting is another equestrian custom of a much more local and idiosyncratic kind. Maryland is very much a horse-breeding state, at one time obsessed with all things hippical. It is also, as I have just noted, a Cavalier colony, and one bordering to the north on the very Roundhead colony of Pennsylvania. Hence, the curious fact that the official state sport of Maryland is jousting. (Sometimes it is necessary to make a statement, you see.) This is not quite as deranged and dangerous a thing as it sounds, since as a rule the form in which it is practiced is ring-jousting (which really involves no juxtatio at all) rather than a potentially lethal duel fought in the lists (the latter, while acknowledged as the sport’s proper form, is a contest honored almost exclusively in the breach rather than the observance). If you are unacquainted with modern jousting and its culture, including its quaint vestiges of chivalric lore and Cavalier romanticism, you can see it well and accurately depicted in the 1964 film Lilith, starring Warren Beatty and Jean Seberg and set in Rockville, Maryland. In any event, I mention this because the St. Stephen’s Day joust was once a sacred custom of my native heath—a kind of latter-day revival of mediaeval Christmas games and matches—which has apparently fallen away. Sic transit gloria juxtationis. Chivalry is truly dead. The days of knighthood are no more.

*******

§7: A beary merry Christmas

Sorry about that.

As a great many of you know, Patrick and I have written two books to date whose casts of characters are based upon a host of soft toys—or peluches, as we also call them—who go back in most cases to Patrick’s childhood. One toy who has not appeared in fictional form so far goes by the name of Stocking Bear. You see, he is a rather seasonally specific sort of fellow—a kind of mer-bear, as it were, or an ursine analogue of a mer-man. He is indubitably a teddy bear, crowned with a Christmas hat, but his lower extremities are a Christmas stocking. In fact, he still discharges the role of Patrick’s Christmas stocking even though Patrick is a fully grown man. Life would seem so much poorer to the family if Stocking Bear did not come out of hibernation—or, I suppose we should say, aestivation—once a year to bring us cheer. We are contemplating a MacGorilla Christmas story for some time in the future, in which Stocking Bear—or his literary avatar—can play a part. For now, here is a picture of him among friends.

*******

§8: Thou dravest love from thee, who dravest Me

This time of year for some reason puts me in mind of my special devotion to my favorite saint, the valiant martyr St. Guinefort. For some obscure reason, veneration of this radiant paragon of charity and faithfulness was sedulously, if ineffectually, suppressed by the Roman Church for many centuries. I do not shelter under the canopy of that particular magisterium, so that does not affect me. Well into the 1970s, the wood near Lyon where the saint’s remains were traditionally said to repose, and where his shrine had been marked out at one time by a circle of trees, was frequently visited by pilgrims seeking miraculous cures for their sick children (children in distress being the special objects of the martyr’s supernatural patronage). The last recorded instance of a child’s miraculous cure by the intercession of St. Guinefort occurred sometime in the 1940’s.

The saint’s tale, which comes to us from the early thirteenth century, is one of the sadder hagiographies you will encounter. Guinefort had been left in charge of the infant son of a knight of Lyon who, on returning one day from a hunt, found the cradle in the nursery overturned with no sign of the baby in sight, and then noticed drops of blood on Guinefort’s chest, and immediately leapt to the conclusion that Guinefort had slain the child. Drawing his sword, the knight killed Guinefort before the latter could so much as voice a protest. Then, shatteringly, the knight heard his son cry out from beneath the overturned cradle. There he found the babe quite unharmed, and soon after discovered the viper from which Guinefort had shielded the child under that cradle and which Guinefort had then killed at great risk to himself. Nearly broken in spirit from remorse, the penitent knight buried Guinefort in a circle of stones shaped like a well and planted memorial trees around it. The legend of Guinefort’s bravery and constancy, and of his tragic death, soon spread throughout the region. Before long the common folk were venerating him as a saint and martyr, and praying to him for the protection and healing of children. All for a time was well.

Then, though, a Dominican friar and itinerant inquisitor named Stephen de Bourbon (1180-1261) came upon the shrine in the course of his slouching peregrinations through the countryside in search of heresies to eradicate. He apparently found something amiss in the cult of the martyr. Who can say why? That was long before the more formal procedures of canonization later adopted by the Roman Church had been established, and many popular devotions to local saints had worked their way into the calendar without requiring any elaborate process of certification. For some reason, though, Stephen was especially resistant to St. Guinefort being accorded any veneration at all, and affected to discern any number of pagan elements in the manner in which the people made their supplications at the martyr’s shrine; so he ordered the stone circle and trees razed, and then proscribed the cult. The locals could not prevent the former, but Stephen could not enforce the latter. When he departed the region, devotions to the holy martyr resumed.

As I say, I have a special devotion to St. Guinefort. I understand that Rome now frowns upon canonization by popular acclamation, and that the cause of any candidate for sainthood these days is rigorously regulated and examined by those empowered by the papacy to conduct the proper investigations. I understand also that unofficial cults of as yet unrecognized saints are discouraged and prohibited by ecclesial authority as a matter of course, lest superstition take root and institutional privilege be compromised. Even so, I cannot for the life of me imagine why Rome continues perversely to refuse to consider the elevation of Guinefort to acknowledged sainthood. Lex orandi, lex credendi, after all. He has many miracles to boast, and I think we can say with absolute certainty that no other saint in the calendar can surpass him in fidelity and purity of heart. It really is a mystery to me.

*******

§9: Just one more thing…

A blessed and holy Christmastide to all of you who keep the feast. And, to those of you who do not keep the feast, plenteous blessings and all joy as well.

Sancte Guinefortis, ora pro nobis.

David, this post filled me with so much joy. I felt like I was sitting next to you and your family at Christmas dinner. What a gift you are to us, to Christendom, and to the entire damn world (and cosmos). I pray and hope you are feeling better after your surgery; chronic pain is a beast I know well. Merry Christmas to you and yours. As I sit here with my dog Bruce in my lap, I can only feel gratitude for your gifts, and your witness.

Merry Christmas to you and yours DBH & to everyone else who may be reading this. Thank you for your engaging and stimulating articles; it's a pleasure to live with them as a weekly feature. Here's to your return to health and happiness in the New Year.

(p.s. I can't help but sympathise with our man with the winter allergies since I'm currently nursing my own time-honoured and traditional festive head-cold and/or flu. But I'm not allowing my spirits to be dampened by this since it wouldn't feel like Christmas without it. Sancte Guinefortis, ora pro mihi)