[The occasion of the republication of this piece—albeit in a somewhat longer form than originally appeared—is an article I came across in Arts and Letters Daily. You cannot keep a good conspiracy theory down, of course, since it is of the very nature of the beast that the absence of any evidence in its favor is itself taken by true believers as evidence of how successfully and perniciously the evidence has been suppressed. Conspiracy theories come in any number of forms, and some are more damaging than others; none, however, annoys me more than the truly imbecile belief that the plays of Shakespeare were written by someone other than William Shakespeare of Stratford; and among its variants none is more irksome than the one that assigns the real authorship to Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. It requires so vast a variety of ignorances—historical, cultural, logical, temperamental, aesthetic—to take it seriously that it might almost be regarded as the conspiracy theory par excellence. But every few years it goes through a period of revival, almost invariably among certain kinds of political reactionaries. And, apparently, this is one of those periods, at least in some rightwing pseudo-intellectual circles. This, in the form that a number of format exigencies prevented from being published in its fullest form originally, is a column I wrote on the topic more than a decade ago.]

Along the coast, it was the sort of morning one can describe only as “Homeric.” You know what I mean: rhododactylic Dawn rising from her loom to spread her shimmering gossamers over the shadowy mountains and echoing sea, dark-prowed fishing-barks drawn up on the milky strand and caressed by the golden foam, the distant thunders of ennosigaean Poseidon and argikeraunic Zeus vying above the wine-dark waves, and so on. Or so I imagine. I would not know. I was actually a few hundred miles inland, in a montane grove of loblolly pines and mixed deciduous trees, awash in flickering sunlight, drinking coffee and reading a newspaper. But I had Homer on my mind just then, for various reasons, and so was in a somewhat epic mood: overflowing with an unwonted sense of animal vitality, the world about me all joy and power, terror and fluent beauty, I was Diomedes upon his day of glory…

Such moods are fleeting, alas. As Chōmei knew, even the remotest mountain retreat cannot keep the pains of transience at bay. My eyes alighted upon a report that Roland Emmerich (director of such cinematic masterworks as Independence Day and 2012) had just made Anonymous, a movie all about how the works of Shakespeare were really written by Edward de Vere, a very minor poet and the 17th Earl of Oxford. All at once, the world had lost its glowing vigor; rosy-fingered Dawn was now a scowling crone with withered talons, laboriously carding the coarse wool of the dreary clouds; the sea had turned to molten lead; Poseidon and Zeus had long ago retired to a managed care facility. I set my coffee aside and went to fetch the gin from the cupboard.

If you are unacquainted with the “Oxfordian hypothesis,” count yourself blessed. It was born in 1920, in a book by a demented English Comtean whom Fate, with her unerring sense of poetic justice, had given the name J. Thomas Looney—a man whose ignorance was so profound it verged on a kind of genius. Looney offered no actual proof for his claim; instead, he attempted to divine the private philosophy of the author of the Shakespearean corpus and then sought out a high-born Elizabethan gentleman who seemed to fit the portrait he had drawn. He also asserted that Oxford was the true author of the works of John Lyly, Anthony Munday, and Arthur Golding (an incoherent farrago of disparate styles, true, but—hey—in for a penny, in for a pound).

Patently worthless as it was, Looney’s book inaugurated yet another conspiracy theory concerning the nonexistent mystery of the “true identity” of the author of Shakespeare’s plays; and, since then, the Oxfordians have elbowed themselves to the front of the “anti-Stratfordian” mob. What is fascinating about the theory itself, in a purely morbid way, is not only that it lacks even a shadow of a scrap of documentary evidence, but that in fact all the real documentary evidence, which is quite substantial, shows it to be incontestably false (and, indeed, leaves no room for rational doubt that the true author of Shakespeare’s plays was Mr William Shakespeare of Stratford).

Now, to say that the Oxfordians have no evidence for their beliefs is not to say they have no arguments. The devout Looneyite can produce a 900-page tome in defense of his delusion at the drop of a lavender-scented handkerchief. But to venture into one of those unwholesome volumes (say, Charlton Ogburn’s psychedelic rhapsody The Mysterious William Shakespeare or the late, lamentable Joseph Sobran’s Alias Shakespeare)1 is to wade into a swamp of misstatements, insinuations, suppressions, confusions, historical blunders, and quasi-occult cryptology. Even so, the sheer weight of all that claptrap has the power to sway the credulous, even among persons otherwise competent in their own fields (actors, journalists, statisticians, Supreme Court justices, and so on) who simply lack enough knowledge to sift the truth from the nonsense. Oxfordianism is to Shakespearean studies what The Chariots of the Gods is to archaeology or The Da Vinci Code is to Christian history, and genuine scholars of Elizabethan and Jacobean literature routinely publish unanswerable demolitions of its claims. But, in a media-addled age, mere scrupulous scholarship is rarely a match for shameless intellectual dishonesty or emotional derangement.

Really, the most hilarious aspect of Looneyism is probably its choice of protagonist. I say this not just because Oxford died about a decade too early to cover Shakespeare’s career (and Oxfordian attempts to re-date the plays accordingly fail dismally); nor because “stylometric” computer analysis (which is frighteningly accurate) repeatedly reckons the odds against Oxford being the “true” Shakespeare as roughly infinite; nor because the conspiracy would have required the complicity of an absurdly large range of Shakespeare’s associates, friends, and collaborators, as well as lawyers and Masters of the Revels and so on; nor because Oxford was a vicious, pompous, humorless, inane fop; nor because of the not insignificant consideration that Shakespeare and Oxford spoke and wrote in two distinct dialects of the English of their time; nor because… (well, the list is endless).

I say it principally because Edward de Vere was almost sublimely devoid of talent. To call his poetry doggerel is a cruel and unwarranted slander of doggerel. True, he enjoyed the admiration of some of his contemporaries; but so did Joyce Kilmer. True, his verse was praised by some of his fellow courtiers, in much the way that Rod McKuen’s was praised by his friends and lovers. But a distance of several centuries tends to put things in proper perspective. At least the Francis Bacon and Christopher Marlowe and John Florio factions in the anti-Stratfordian cult champion men who actually possessed literary gifts. By contrast, Looney chose a man who was, if anything, the anti-Shakespeare of his age. But Oxford was an aristocrat, and Looney believed fanatically in class distinction and purity of blood. A few lesser critics had been claiming for decades that Shakespeare’s plays were written by some widely-traveled man with a classical education and an intimate knowledge of the inner workings of Elizabeth’s court, rather than by some tradesman’s son, educated at a grammar school. Nothing could have been further from the truth, actually—unlike the plays of, say, Ben Jonson or the “University Wits,” Shakespeare’s show no signs of excessive classical or cosmopolitan culture—but Looney did not know this, having little education himself, and the idea of a Shakespeare with aristocratic pedigrees suited his social philosophy perfectly.

I suppose I should not really care. Oxfordianism is annoying and silly, granted, but one can hope that in time it will subside in popularity. Only a person whose education is more boast than substance could believe it. But I find the whole phenomenon morally troubling. I cannot prove it (which should not bother the Looneyites), but I suspect that the most fervent Oxfordians are motivated principally by resentment: the capon’s envy of the cock, so to speak. Persons of mediocre talent, consigned to a middling rung on nature’s scale, but who imagine themselves tremendously gifted, often take violent offense at real greatness. And Shakespeare’s genius is so exorbitant, and the fecundity of his literary imagination so monstrous: the thought that such prodigious art was produced just by nature, unassisted by special advantages and attainments, must seem intolerable to a certain sort of deeply inadequate person. Ah, but if in fact the “real” writer was a child of privilege, forged in the crucible of social eminence, possessed of secret inner knowledge—why, then, his genius is somehow more explicable. And that in turn makes more explicable the conspiracy theorist’s own lack of achievement, for this too can be ascribed to a conspiracy—a conspiracy of circumstance, the connivance of fate, a cosmic miscarriage of justice.

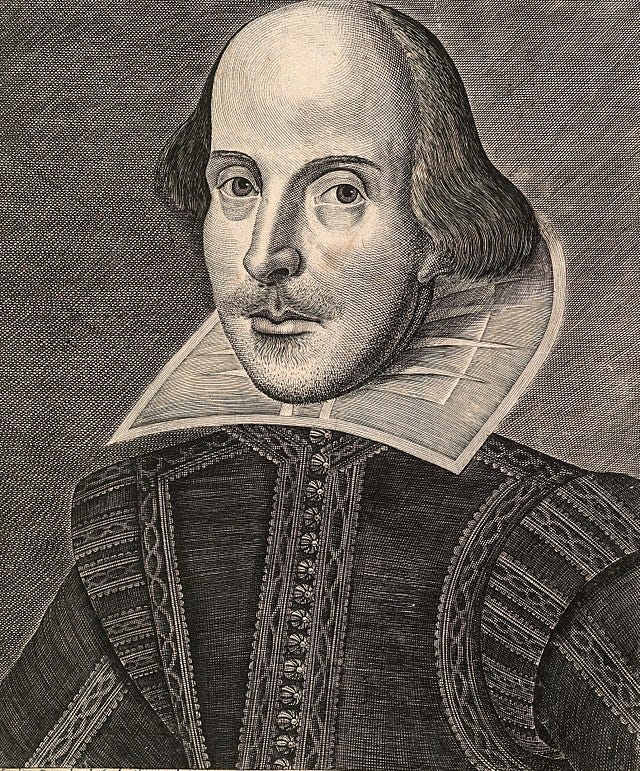

Who knows, though? The real issue is one of common decency. When we talk about, say, the authorship of Homer, we know that the attribution is irreducibly uncertain: part legend, part conjecture, and part (but what part?) truth. In the case of Shakespeare, however—one of the few literary figures who can plausibly be said to be greater than Homer—we know exactly who he was, when he lived, how he earned his bread and reputation. To attempt to rob him of his posterity out of envy, foolishness, or callous indifference to the truth is perfidious. There is no mystery about Shakespeare other than the perennial mystery of genius, which is at once prodigal and parsimonious: distributed regardless of social station or just deserts, but to only a very few. This truth may be excruciatingly galling to some, but to persons of good will and healthy mind it should simply elicit grateful admiration and ungrudging recognition.

And, anyway, if these stridulating nonentities really want to make their conspiracy theory interesting, they need to fill in the cracks better. No Oxfordian has yet convincingly responded to the “stylometry” problem, for instance. If they were really on their game, however, they would argue that this merely exposes another conspiracy hitherto unsuspected, and that the works commonly attributed to Oxford are clearly products of another hand. I propose Francis Bacon. As for the inevitable discovery of similar incompatibilities between Bacon’s style and “Oxford’s,” one need only argue that, of course, “Bacon’s” works were really written by someone else altogether. As for who this might have been, the answer seems obvious: William Shakespeare of Stratford Upon Avon, who it turns out was a far more cunning and mysterious figure than any of us ever suspected…

Sobran liked to pretend that he possessed so profound an “expertise” in Elizabethan and Jacobean literature (about which he knew very little) that he could all but infallibly detect the voice of Oxford in Shakespeare’s plays, just as he could detect the voice of “Shakespeare” in Oxford’s verse. The countless “parallels” Sobran claimed in Alias Shakespeare to have found in the two men’s work are either nothing more than common turns of phrase from the period in which they wrote or mirages generated by Sobran’s eerily tin ear and pedestrian sensibility. An amusing demonstration of the fraudulence of Sobran’s claims comes in an appendix of his book, where he reproduces the entire corpus of Oxford’s few extant uncontested poems from Steven W. May’s The Elizabethan Courtier Poets, in order to mark out a large collection of resemblances he thinks can be identified between “Shakespeare” and Oxford. Alas, Sobran failed to pay attention to Mays’s admirable critical apparatus. As a result, he accidentally reproduced a poem by Thomas Churchyard—another court poetaster—to whose end Oxford had added a dozen lines, mistaking Oxford for the author of the entire piece. Moreover, in the sixteen lines written by Churchyard, Sobran claims to discover sixteen parallels with the works of Shakespeare. That is a far higher rate of resemblances, per line of verse, than he “discovers” anywhere in Oxford’s authentic poems. This is hilarious, of course. It is also typical of the quality of Oxfordian “scholarship.”

The Earl of Oxford should be celebrated for what he did give us, which is the anecdote in Aubrey that he let off a particularly fruity one before the Queen and felt so humiliated that he left the country for seven years. Elizabeth greeted him upon his return with the gracious words “My Lord, I had forgot the fart.”

Have pity on me DBH for I have erred. I have tasted of the Oxfordian fruit. It was the videos of Alexander Waugh wot dun it, Guv'nor. Whatever you do, good people do not check them out for yourselves on youtube. Do not do as I have done. *jangling of chains*