Thoughts In and Out of Season 2

On Vladimir Nabokov, Thomas Mann, Ty Cobb, Better Call Saul, Native American Rights...

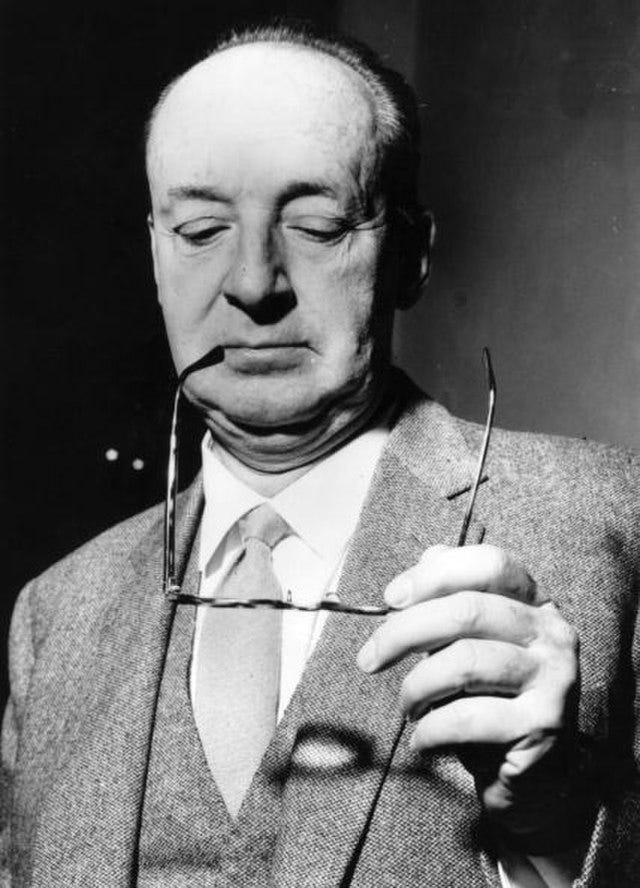

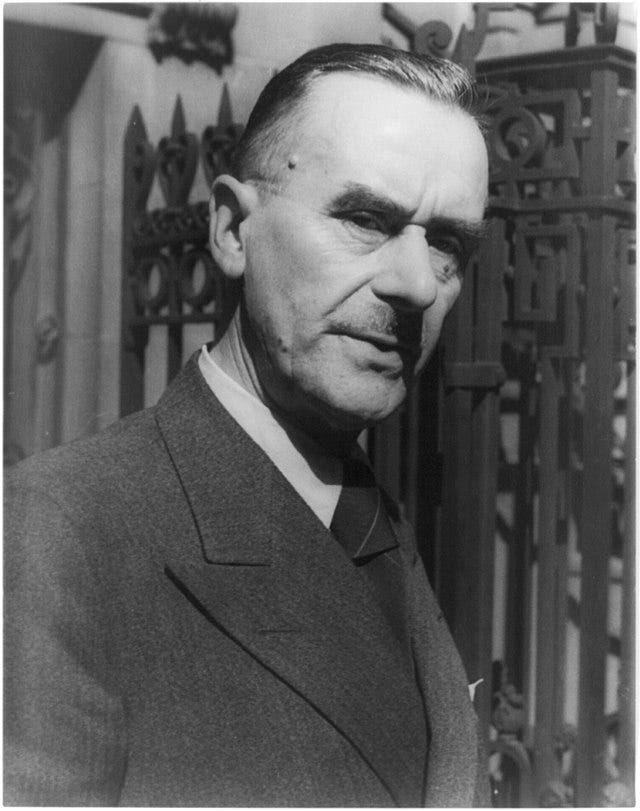

1. A significant part of the territory of my imagination and taste was conquered and colonized by Vladimir Nabokov when I was sixteen; that was when I read Pale Fire for the first time, a good deal of it while skipping classes and seated in the vertiginous, latticed catwalks above the large auditorium stage in my high school. (It was an open-space and experimental public school, you see, full of teachers who—what with their graduate degrees, cannabis habits, and penchant for Gramsci—were generally indifferent to my absences so long as I passed exams and handed in papers on time.) I certainly have never regretted the terms of my surrender, but in later years I occasionally had to struggle against its more questionable effects. Pale Fire came at such an impressionable moment in my life that, for better than a decade, I was susceptible not only to the enchantment of VN’s art, but to all his critical verdicts on other writers. This was not disastrous, as it happens. He was more often right than wrong. But he also suffered from a narrowness of sensibility that frequently turned what should have been (at least) a tepid enthusiasm or (at most) a mild distaste into a vehement hatred. He had no ear, for instance, for the music of abstract ideas (just as he had no ear for music itself), and so—despite his own attempt at a treatise on “The Texture of Time” in Ada—he could never really enjoy the aesthetic pleasure that a fetchingly strange philosophical excursus in a work of fiction might provide. For a long time, I took his word on everyone except Dostoyevsky (though there, curiously enough, I later came around to something like his view of the matter on my own), and well into my late twenties I could not read certain authors except through the bile-colored spectacles I had inherited from him. Sometimes I even struggled to convince myself that I disliked an author more than I really did. A good example would be Thomas Mann. Now, to be clear, I still would not place Mann on any list of my favorite authors, however long; a good many of his books, conscious as I am of my mortality, I would never dream of revisiting; at his worst, he was not merely ponderous as a writer, but somehow ponderously ponderous. But, as I grew beyond my initial acquiescent acceptance of VN’s scale of aesthetic values, I also came over time to appreciate certain aspects of Mann’s work that VN had clearly failed to see. Most conspicuous among these would be the wry sense of humor it often reflected. One cannot miss it, of course, in Felix Krull, which is—mirabile dictu—a comic masterpiece. But it is there also in a good deal of Mann’s literary corpus, usually carried along on the even flow of a dispassionately ironic tone, and it absolutely permeates his greatest novel, The Magic Mountain.

2. Last month, I returned to Mann’s Zauberberg for the first time in many years. I found much of it unchanged from a previous visit: the protagonist—the amiably mediocre Hans Castorp—was still the vapid, halcyon eye of the storm, somewhat inconsistently developed as a character but nevertheless a usefully pliant medium for conducting the reader into the story; the vaguely Dickensian figures in charge of the sanitorium were, as I had recalled them to be, autocratic, pompous, and ambiguously concocted from equal parts professionalism and charlatanry; the incidental characters discharged their rôles in the story adequately; and the two most interesting figures in the tale, Settembrini and Naphta, are as vivid as I remembered them. Other aspects of the novel, however, struck me as new, in part because I had forgotten them but more because I had not been able fully to appreciate them when I was 20 years old. One of these was that aforementioned humor, which was more crisply audible to me this time around than it had been before (at least, as far as I can recall). Another was the sheer intelligence and erudition of the author, which I suppose I am better able to appreciate now as I near the end of my scholarly career than I was when I was just embarking upon it. Hans Castorp’s long meditation, for instance, on the mysteries of life and consciousness, as well as his reflections on the relation of time to consciousness—a little implausible perhaps for a character so lacking in intellectual depth, but never mind that—demonstrates a truly acute and sophisticated understanding of the philosophical perplexities generated by the modern mechanistic view of reality (would that there were many analytic philosophers in our time that were anywhere near so perceptive). The long debate between Settembrini and Naphta over the political radicalism of the church fathers and mediaeval monastics demonstrates a wide knowledge on Mann’s part of patristic literature and early Christian history, of a sort one rarely finds even among specialists in the field. Above all, though, what I had most thoroughly forgotten or failed to notice in the past was the ominous atmosphere of a civilization in its death-throes. Of course, the action of the novel takes place in the seven years leading up to the Great War, and so a certain sense of approaching catastrophe is inevitably part of the plot; the last we see of Hans Castorp is his dwindling figure charging away into the smoke of the battlefield. But Mann manages to convey not just a sense of impending disaster, but a sense also of the nihilistic impasse of so much of late Western modernity in general. The governing conceit of the book furnishes an ideal metaphor for Europe on the verge of its final cultural suicide: a sanitorium where everybody is frail and narcissistic, genuinely ill or hypochondriac or a little of both, or is at least encouraged to be so; a place of fantasy and withdrawal, serenely indifferent to the gathering darkness; a malignly magic realm where even the young are already old, and can become young again not through a recovery of innocence, but only through the naiveté of pointless self-sacrifice. The general predicament is most lucidly expressed in the (ultimately tragic) antagonism between Settembrini and Naphta. Both are right and both are wrong, about everything. Both understand the crises of their age—the loss of faith, the incapacity for community, the disenchantment, the utter metaphysical boredom—and both imagine they know what the solution should be; but each constantly reveals the flaws in the other’s vision of things, and by the end it seems obvious that there really is no protection against the destructive forces released by the disintegration of European Christendom. Settembrini is the progressive idealist who looks to the future, Naphta the “Christian” reactionary who looks to the past; and yet, at the same time, Settembrini is also the conservative and traditional humanist clinging to the classical verities and Naphta is also the nihilistic radical seeking the overthrow of reason and order; and the fate of each character—a final descent into total infirmity, a final act of self-destruction—is exactly in keeping with the peculiar hopelessness of his position. What struck me most forcibly on this reading was at once the seeming insolubility of the problems the two characters were confronting and also the eerie similarity of that insolubility to the public debates and ideological struggles and civic pathologies of our own moment. Of all the impressions the novel made on me this time around, that was certainly the most portentous.

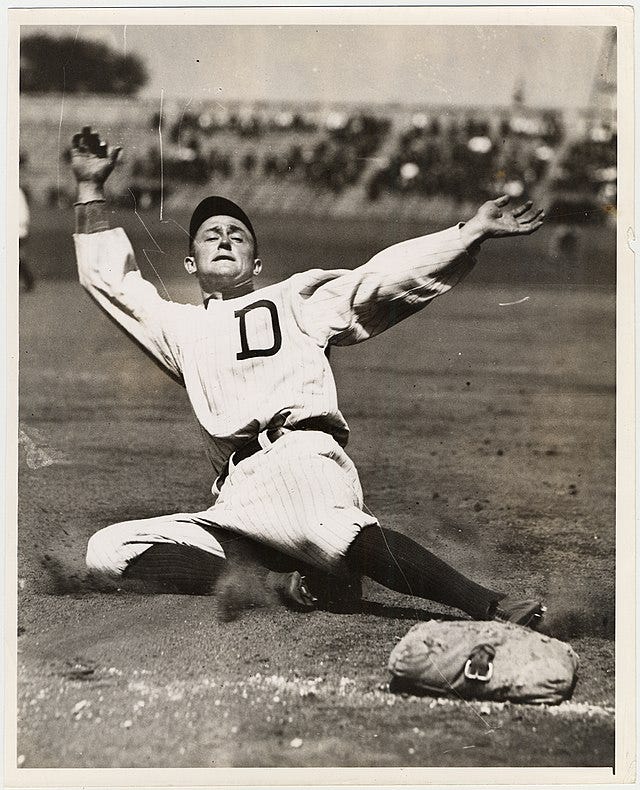

3. But on to more important things. Baseball and the moral order of the universe, as we all know, are mysteriously but inextricably involved in one another. The game, well played, is not merely an allegory but a direct embodiment—even an incarnation—of the deep structures of rational goodness that bind reality together into a meaningful and beautiful whole. By the same token, the abiding moral truth sustaining our existence depends in ways too profound to name and too various to enumerate upon the well-turned double play, the suicide squeeze perfectly executed, the pristine line drive into the gap, the astonishing outfield assist, the daring steal of third, the crucial sacrifice fly in late innings, the majestic home run, and so forth. So deep and reciprocally constitutive is the complementarity between the game and that cosmic harmony that the very distinction between absolute and contingent, archetype and epitome, seems utterly relative. Baseball is the radiant revelation of the eternal potencies that reside in being’s depths; but, conversely, being achieves its full actuality as living and self-reflective spirit only in baseball. Baseball manifests timeless truth, but timeless truth exists because of baseball. What then is the consequence when the sheltered garden paradise of the game is invaded by the serpent of moral falsehood? Well, the answer is obvious. The very fabric of reality is imperiled. The pillars of the universe begin to shake. For this reason, inasmuch as they serve to redress an injustice of positively ontological significance, no more important books have appeared in our age than Charles Leerhsen’s Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty (2015) and Tim Hornbaker’s War on the Basepaths: The Definitive Biography of Ty Cobb (2017), which together have at last begun to free the legacy of the Detroit Tigers’ most legendary player from the egregious and bizarre slanders that have been heaped upon his memory for better than half a century now. Really, the word “slander” is strangely inadequate here. The picture that has emerged of Cobb since 1961 is not merely inaccurate; it is practically the total reverse of reality. And yet it was so successful a fiction that, but for these two books, it might have continued to eclipse the true story indefinitely. I myself accepted it as the established truth of the matter for most of my life. I should have listened to my father, who was born in 1925—three years before Cobb’s playing career reached its end—and who had warned me that something here was seriously amiss.

4. Anyone who has any real knowledge of baseball knows that Ty Cobb was the greatest pure hitter in the history of the game, and among the five or ten greatest players ever. His career .366 batting average and his 4065 total runs remain records that no one is ever likely to break. His 4191 hits were surpassed only by Pete Rose, an immeasurably inferior talent in every way other than at amassing singles. His 892 stolen bases set the mark for the modern game that Lou Brock finally bettered in 1977; his 54 steals of home is a mark that no one else has ever come near to matching or ever will. And those are only the most startling of his numbers. He was also the most exciting player of his day, and among the three or four most exciting ever. But what almost everybody also thinks he or she knows about Cobb is that he was an altogether monstrous human being: a fanatical racist, a vicious and unprincipled player, a surly redneck from the deep South, a pistol-wielding lunatic, and a cruel and violent thug who may have been responsible for the deaths of as many as three men. Various horrible stories have become more or less canonical: there is one, for instance, about him assaulting a black groundskeeper who had supposedly has the effrontery to congratulate him for his play on the field, and then attacking the man’s wife when she came to her husband’s assistance; there is another about an altercation in a Cleveland hotel in 1909 that ended with a black watchman stabbed to death; and so on. The wretched 1994 film Cobb even went so far as to add an attempted rape to the popular portrait. It turns out that none of these stories—none of them—nor any of the many others of a similar nature that have become part of the legend, is true. As my father had informed me, with a slightly furrowed brow, as far as he could recall the reputation that Cobb enjoyed at the time of his death was that of a flawed man, and certainly a bit of a brawler—as all good baseball players of his time were expected to be—but otherwise a decent soul who had been very much in favor of baseball’s racial integration, and had often been widely praised for his kindness and generosity, including by a number of black friends and associates of many years. And, as it happens, my father was right, certainly as far as the testimonials of those who had actually known him went. Norman “Bobby” Robinson, a Negro League player for many organizations, among them the Detroit Stars, had been close to Cobb for many years, and had spoken up on Cobb’s behalf when the scurrilous stories began to take hold of the public imagination, insisting that “there wasn’t a hint of prejudice” in the man. Another black friend, Alex Rivers, who had for a time been an employee of Cobb, not only professed to have loved the man but named a son after him. At the time of Cobb’s death in 1961, the Los Angeles Sentinel—arguably the flagship publication of the independent black press in America at the time—ran an obituary under the title “Ty Cobb Backed Negros” and praised him for his advocacy of “racial freedom in baseball.” And indeed, when the Sporting News interviewed Cobb in 1952 and asked him about Jackie Robinson and the integration of the game, he replied that certainly black players had “every right to compete in sports” and “should be accepted not grudgingly but wholeheartedly.” Moreover, Cobb had attended a great many Negro League games over the years, sometimes throwing out the first pitch and then sitting in the home-team dugout talking baseball with the players. And he was certainly unstinting in his praise for that first great generation of black players who entered the major leagues. He called Roy Campanella (whom he thought the player of that time most like himself in style) one of the “all-time best catchers” in the game; and, when Campanella suffered the accident that left him paralyzed, Cobb wrote an emotional letter to the owner of the Dodgers thanking the organization for the public tribute they had arranged for “this fine man” at a game played in his honor. Cobb’s favorite player during the last decade of his life was Willie Mays. Nor, in fact, was it only in those later years that Cobb’s behavior suggested something very different from the racial hatred later attributed to him.

5. From 1908 tom 1909, for instance, Cobb was the chief friend and protector of Ulysses Harrison, the Tigers’ young bat-boy and “good luck charm”; when the team was on the road, Cobb regularly defied Jim Crow restrictions in the South by hiding Harrison in a sleeping berth on the train and in his own room at the hotel. Even in the 1920’s, when it was very uncommon indeed, he had cultivated friendships with Negro League players. There had been nasty stories about Cobb in his playing days, true; but even the tales of his unethical play were exactly the opposite of the truth. Sadly, a good deal of the sports journalism of his time thrived on rumor, hearsay, scandal, and every kind of sensationalism. And Cobb began his career in an era when the game on the field was far rougher than anything we are accustomed to today and when fistfights and bitter rivalries were practically de rigueur (and when, in fact, men in general were expected to engage at intervals in fisticuffs as a matter of course). Competition bred resentments and resentments bred lies. The story about his assault on the black groundskeeper, for instance, was made up by a catcher who hated him. And, of course, Cobb did come from the deep South—from the little rural hamlet of Narrows, Georgia, to be precise—and so it was no great stretch of the imagination to assume he must harbor a certain amount of racial hatred in his breast. But, in fact, far from being the slouching hayseed he was later depicted as being, he came from an educated middle-class background, and his father had been a progressive state legislator who championed racial justice (and who had even once succeeded in thwarting a lynching). Cobb himself was quite well-read, with a famously large taste for good literature, and was known for comporting himself in a somewhat theatrically courtly manner; he liked to speak of baseball, for instance, as an arena in which men were given the opportunity to exhibit “honor” and “gentility”; and, for all his “notorious” irascibility, he was also regarded by many who knew him as frequently polite to a fault.

6. The chief source of the evil reputation that Cobb acquired after his death was a journalistic hack named Al Stump who, fairly early in his career, had been banned from almost every respectable organ of news or opinion in the country as a result of his relentless dishonesty. Even the yellow press tended to keep him at a distance. But in 1961 he was inexplicably hired by the publisher of Cobb’s autobiography as its ghost-writer. Cobb was in poor health (not to mention depressed and somewhat bitter at how thoroughly he had been forgotten) and simply could not complete the final version of the book on his own. Stump, however, began altering the text to make it more scandalous and exciting. When Cobb discovered what Stump had done, he initiated a lawsuit to prevent publication, and would certainly have won it had he not died before it came to court. And so Stump’s corrupted text went to press. From there, the lies continued to expand and pullulate. In 1985, the (apparently extremely lazy) academic historian Charles C. Alexander released what certainly looked like a respectable biography of Cobb–it was published by Oxford University Press, after all—but in its pages he not only credulously repeated the lies that Stump and others had spread about Cobb, he then exacerbated the injustice by making a series of outrageous and unwarranted claims that it required only minimal research on the part of Leehrsen to refute. Not only does Alexander’s book repeatedly exaggerate the violence of Cobb’s various altercations (such as that Cleveland hotel incident from 1909, which resulted not in anyone’s death but only in a scratched wrist); it again and again states that Cobb’s antagonists were black men when in fact they were white. And then in 1994, Stump—who was still alive and making money by selling fraudulent baseball paraphernalia—published Ty Cobb: The Life and Times of the Meanest Man Who Ever Played Baseball, which formed the basis for that execrable film I mentioned above.

7. Why am I spending so much time on this matter? Well, for three reasons. The first is that the cruel caricature of Cobb invented by Stump and enlarged upon by Alexander and others is so gross a distortion of the truth and so hideous an injustice that it is nothing less than a moral necessity to struggle to erase it from public consciousness. The second is a matter of my own peculiar convictions: you see, I think of baseball as a high spiritual discipline, and while I am willing to believe that an imperfect man can be a great player and even that an evil man can be a decent player, I cannot for a moment make myself believe that a truly evil man can be a truly great player; and no player was greater than Cobb; if I really believed that a violent racist and murderer could actually have performed on the field with such exquisite virtuosity and inspired genius—for God’s sake, the man once stole second, third, and home on three consecutive pitches1—then I would have to lose all faith in the moral structure of the universe. And the third is that the story of Cobb’s postmortem mythology, and of how thoroughly it has displaced the true story of the man, is a stark reminder that a very great deal of what we think we know about the past and about other persons may very well be pure (or, for that matter, very impure) fiction. And that is a sobering thought.

8. Three readers have sent me emails related to my Q and A articles, all basically asking the same question: Are there any forms of current popular culture that I enjoy (any films or television, that is)? This is a partial answer. For many years, I avoided watching episodic television. Not to put too fine a point on it, it was not very good for the most part. When I fell extremely ill in early 2014 (as I relate in Roland in Moonlight), I began watching some of those programs one regularly hears praised as evidence of our “golden age of television”; and, I have to say, I was genuinely impressed by quite a few of them. The Wire, for instance, even though it was a little too accurate a portrait of the sadder side of the city in which I was born, was impossible not to admire. I became genuinely addicted, however, to Breaking Bad, which was so much better written than any of the television of my youth—and better written than just about every studio film made since the 1970’s—that it astonished me. It was the perfect balance of Dostoyevsky and Ed McBain, with just a hint of Lawrence Sanders here and Charles Portis there. I did not even mind the somewhat fantastic conclusion of the series. When, however, its sequel (or “prequel”) Better Call Saul came out, I was hesitant to watch it, fearing it would prove to be an inferior product that would only diminish my memory of the original program. But I watched. Now, in its final season, having just returned from its mid-season break, the show is dwindling down to its end over half a dozen episodes; and I am prepared to say not only that it is the better of the two programs, but that it may be the finest wholly original program ever to grace American television (or television anywhere). Like its predecessor, it is a grim portrayal of the gradual destruction of a soul, though now perhaps with somewhat greater subtlety and nuance, and with a richer range of characters. Comparisons aside, though, the quality of the writing has proved consistently astounding, and never more so than in these concluding chapters. Anyone who has followed the story—and I will give nothing away—will know that the final episode before that mid-season break was at once shocking and brilliant. It arrived in its closing minutes at a denouement (ominously announced by the slight flickering of a candle’s flame) that made perfect sense of the entire narrative of the series up to that point, and of the current season in particular, but that was (for me, at least) wholly unexpected until the moment just before it occurred. The construction of the story was so ingenious, and its moral and emotional power so unexpectedly intense, that I was left amazed. I do not know what it tells us about the current state of our culture that good writers have more or less been banished from the movie industry and have had to take their wares instead to television; but I am glad the medium as it now exists can make room for them. I also do not know what to make of the reality that there are television programs so much more competently written than most novels today. But, whatever the case, I can at least assure my three correspondents that, yes, I do watch television, even sometimes when something other than baseball is on; and that, moreover, in the case of Better Call Saul I feel positively elevated by having done so, because the program is a genuine work of finely wrought art.

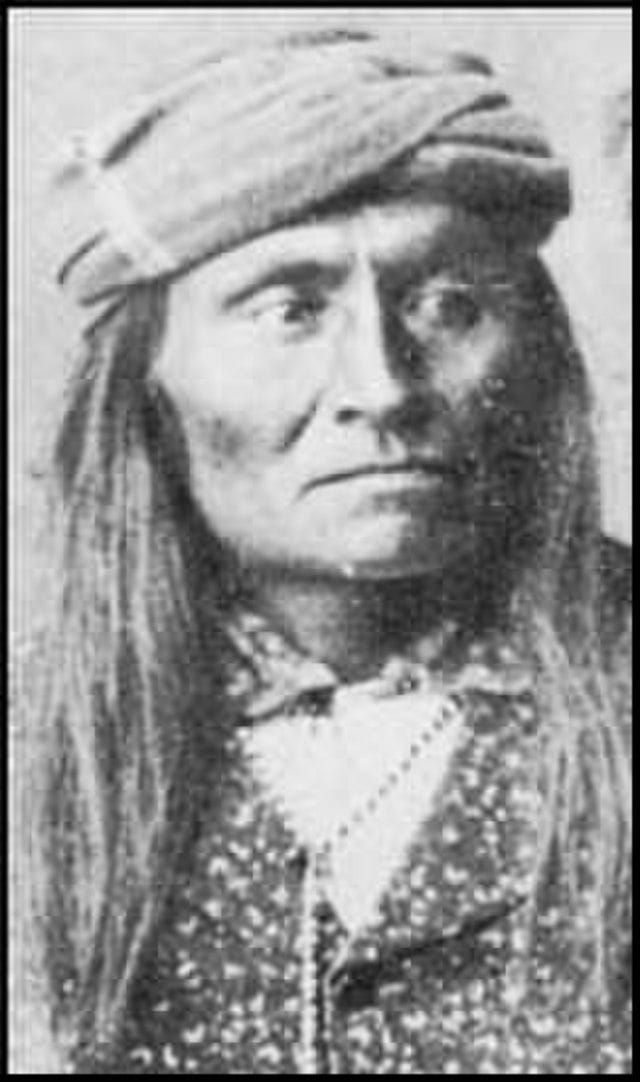

9. For reasons that I never thought to inquire after, one of the civic causes that has been a constant in my family life over a number of generations (I am not sure how many) has been Native American (or Native Peoples’ or First Nations’ or American Indian) rights. My distaff grandmother (“Nana”)—who knew the value of a penny and was not really much in the habit of playing Lady Bountiful—dutifully made her yearly contributions to Native American charities. As kids, my brothers and I were more or less encouraged to pull for the Indians when watching Westerns. Johnny Cash’s “Bitter Tears” album occupied an honored place among a collection of LP’s that generally favored very different genres of music. Little Big Man—in the form both of Thomas Berger’s original novel and of Arthur Penn’s film—was a great favorite chez Hart. In our home, George Armstrong Custer was regarded (correctly, of course) as the moral equivalent of Satan, while the list of heroes of “American” history we most revered included figures such as Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Chief Joseph, Cochise, Mangas Coloradas, and Geronimo. When my fifth grade class was given the assignment of writing short reports on whatever episode in American history each of us especially wanted to celebrate, I wrote mine on the Battle of Little Bighorn. That same year, I chose to write my final book-report (delivered viva voce to the whole class, incidentally) on Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (for some of the children, it was the first time they had heard the word “genocide”). And so on. Make of this what one will. I mention it only to provide some context when I mention (as I am doing now) that I try to keep an eye on developments in the relations of the United States to the sovereign nations of the Native Peoples within its boundaries. The recent Supreme Court term has produced so many enormously controversial decisions—the overturning of Roe and Casey most conspicuously, but also its rulings on EPA regulatory powers and gun-control, not to mention the one probably still forthcoming regarding the popular franchise—that it is little wonder another fairly radical decision went relatively unremarked by the national press. On June 29th, the court handed down a decision in a suit by Oklahoma against the Cherokee Nation regarding reservation jurisdiction. It was, admittedly, a difficult and complicated case—it concerned the possible state prosecution of a case of child-neglect allegedly committed by a non-Native American resident of the reservation against his Cherokee step-daughter—and certainly it required some real degree of jurisprudential wisdom to deal with the ambiguities of the situation. Wisdom, however, was not what the court provided. In a 5-4 decision (Neil Gorsuch breaking with the conservative wing on this occasion), the court essentially stripped all the indigenous nations of much of the sovereignty they enjoy by treaty. Not that the US has ever actually honored any of the treaties it has made with the Native Peoples (it has broken just about every damned one of them), but in this case the treachery was committed in the name of constitutional principles that, as a matter of simple fact, do not exist. According to Brett Kavanaugh, writing for the majority, “Indian country within a state’s territory is part of a state, not separate from a state.” That is simply not true, and no jurist at any level can make it true. Indian lands are sovereign exceptions to state jurisdiction, and only the federal government enjoys any discretion in tribal affairs alongside the tribal government. Even then, the federal rôle is that of a protector toward a protectorate, not one of a government to its own completely sovereign territory. The Supreme Court has no grounds—and, frankly, no legitimate jurisdiction or authority—for the ruling it handed down. (Then again, I suppose, authority is ultimately only power, and power is whatever you can get away with.) Even Gorsuch, in his dissent, described the decision as “a grim result” and—referring to the earlier decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020) that reaffirmed and guaranteed reservation sovereignty in the state—expressed his “hope” that “the political branches and future courts will do their duty to honor this nation’s promises even as we have failed today to do our own.” A fine sentiment, of course; but, as for the plausibility of such a hope, the full weight of American history lies in the balance against it.

10. Yes, the rebuilding Orioles are playing extremely well at present (as I write, they have won nine games in a row). The young talent—which is plentiful—is coming into its own. And the new dimensions of Camden Yards’ left field have turned the venue into a pitcher’s park, despite the considerable natural power in the lineup, and have obliged the home team to play a style of baseball eerily reminiscent of the classic game, with a huge reliance on pitching, speed, stolen bases, dazzling defensive play, bunts, and so forth. Thanks for asking. (Well, no one did, but I am sure everyone meant to.)

June 12, 1911–111 years ago to the day at the time of writing.

Speaking of TV shows, I was wondering if you had the pleasure (depending on your taste) of seeing the Netflix show, "Dark?" You'd probably get more out of it since it is in German and I don't understand a lick of it. For me, that's easily the greatest television show in the last decade but I am also enamored of science fiction. If you haven't, I warmly recommend it. I find it fortuitous or perhaps even providential that I was watching it while reading Maximus for the first time in Jordan Daniel Wood's class he gave online a year ago. As they say in the show, Der anfang ist die ende und der ende ist der anfang. Sic mundus creatus est.

https://libredd.it/img/8dpj7j7k76u41.gif

Your musings on Better Call Saul came as a pleasant surprise–it is indeed a masterpiece. I'm both looking forward to and dreading the remaining episodes.